ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Transcending Boundaries: Curating a Digital Exhibition

Isabella Cammarota

In 2020, like many others, my research project was affected by the pandemic. During this time, the internet was my only tool to access the world outside of my house. I spent a lot of time trawling through Instagram and, in this process, come across numerous social media accounts of Tibetan artists and creatives. At the same time, I was reading Shireen Walton’s works on digital ethnography which played a pivotal role in my research methodologies. Her “reconceptualization of the field”, in which fieldwork can be conducted beyond geographical space/presence, “with/in a country, community, or society from a location that is physically distant,”[i] pushed me to think about the role of digital media in the current developments of Tibetan contemporary art. In the summer of 2020, I came into contact with the Yakpo Collective, a group of young Tibetan artists and creatives based in New York City, whom I had encountered online. During this time, I collaborated with them as curator and editor in the installation of their digital exhibition “Transcending Boundaries”. This paper is a collection of the data I have gathered during my participation in the exhibition and a reflection on the role of digital media in the objectives, methods, and curatorial practices adopted by the Yakpo Collective.

The Yakpo Collective was founded in 2019 by Tsewang Lhamo. As an emerging collective, their mission is to: “provide a platform for Tibetan contemporary artists to exhibit their artwork and present their ideas to a growing audience. Through this mission, we want to promote Tibetans taking back control of their narrative, rather than have other media outlets define and misrepresent our community.”[ii] By providing a space for young upcoming Tibetan artists to exhibit and sell their work, the aim of the collective is to engender discussions about on how “immigration, intersectional identity, and generational trauma informs the shared Tibetan experience.”[iii]

Their first exhibition “Tibetan Contemporary Art: The New Wave”, was held between July 26th and July 28th, 2019 at the Here Now Space in New York City. After this exhibition, the core team of the collective was formed and its members are Tsewang Lhamo, Tsejin Khando, Kunkyi Tsotsong, Pema Dolkar, and TC Andrugtsang. The show had a great turnout and as a result, the collective’s Instagram account started to gain a lot of traction. In 2020, the Yakpo Collective further built its social media following with the launch of the Spotlight Series, a series of interviews with Tibetan artists, on their Instagram TV.

Unable to organize their annual summer exhibition in person due to Covid-19 restrictions, the collective decided to experiment with setting up a digital exhibition, the theme being “Transcending Boundaries”. Beyond the conceptual interest for the collective of trying out a new format, there were a number of practical reasons to choose to undertake an online exhibition. Without access to funding and other resources, a digital exhibition offered accessibility and flexibility. This is, most practically, due to the low start-up costs of digital technologies. Secondly, digital media offers the potentiality for wider distribution and visibility. For creatives such as Yakpo at the beginning of their careers, these qualities afford a level of autonomy, and potential success, that may permit to circumvent “the conventional route of traditional gallery representation that was paradigmatic of success in the world of contemporary art.”[iv] Furthermore, as Walton observes when curating her digital exhibition on Iranian photoblogs, the transnational mobility a digital exhibition affords lent itself to geographically dispersed communities.[v] This struck the collective as one of the main advantages of installing a digital exhibition. The participation of the artists would not be limited geographically, and anyone, regardless of their resources, could submit their artworks online.

As the project started to take shape, a team was put together with collaborators based between New York, Kathmandu, and London. Spread across large distances and with travel restrictions in place, the organization, curation, and promotion of the project had to be held completely online. Each collaborator had a defined role, but during the progression of our Zoom meetings and conversations on the group chat these were dissolved into a fully collaborative enterprise. During the installation of the exhibition, everyone took part in communicating with the artists, selecting the artworks and curating the exhibition, overseeing the development of visual materials for marketing, writing press releases, conducting email marketing campaigns, posting on social media, and planning advertising strategies.

The first step in organizing the show was an open call on social media and inviting some of the artists the collective was already in contact with. The theme for the exhibition “Transcending Boundaries” was chosen. Offering a broad interpretation of the theme, we received a large number of submissions from artists from both inside and outside Tibet. Once we received the submissions, the concept of transcending boundaries took shape. The theme was informed by the conversations taking place among us isolated in our houses during the Covid-19 crisis and how technology has come to substitute physical interactions with the world. Through this exhibition, the collective decided to take advantage of the digital and give space to the artists to transcend notions of geographical boundaries when thinking about the Tibetan experience: “from tangible boundaries of physical touch to personal borders which dictate feelings of identity and belonging, the exhibition surveys the extension of this word.”[vi]

The subsequent step was to choose the software for the exhibition. The vision was to create a three-dimensional space that replicated the experience of moving around a physical gallery but also took advantage of its digital nature to generate a space made specifically for the art. Tsewang Lhamo was in charge of this aspect of the curation and settled on the virtual gallery software “kunstmatrix”. This tool allows the curator to create one’s own personalised architectural exhibition space in three-dimensions and offers its online visitors a simulated version of a visit to the “real” galleries.[vii] However, as McTavish notes for the digital galleries of the Rijksmuseum, these are empty and the digital visitors do not so much “walk” through the space as occupy fixed positions in the centre of galleries and the walls rotate creating the illusion of moving their “head”. Visitors can relocate to another fixed location but their experience of the gallery remains constrained by the predetermined viewing positions established by the software designers. The visitor’s experience of movement is further restricted as the empty digital gallery is defined in exclusively visual terms.[viii] This is also the case for the “kunstmatrix” software and the space for the “Transcending Boundaries” exhibition was conceptualised as a single room with the artwork hung on its white-washed walls (Fig. 1).

Once the exhibition space had been established, in the following meetings we selected the artworks and discussed how the works could illustrate the narrative of transcending boundaries.

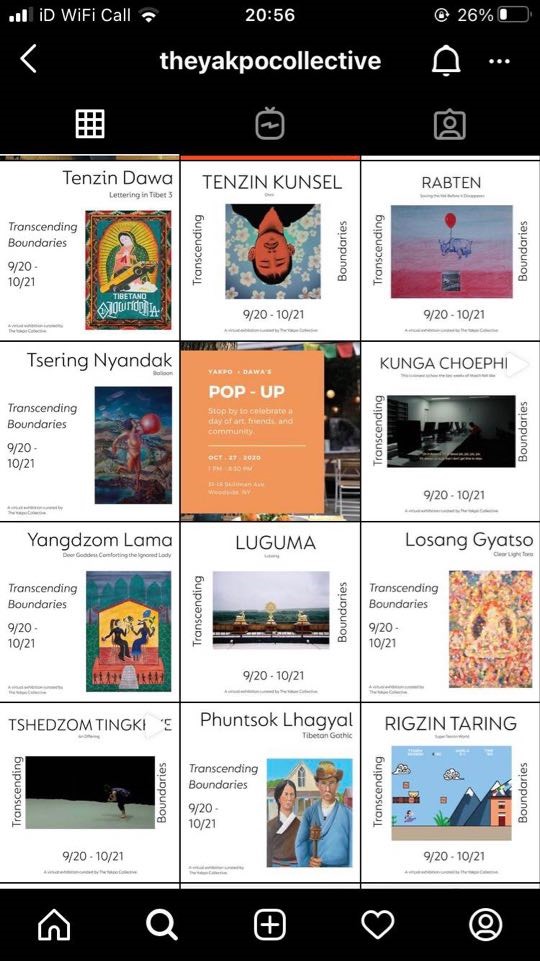

Out of over forty submissions, thirty-one artworks were selected by thirteen artists from the US, Canada, Europe, India, and Tibet: Khenzom Alling, Tsering Nyandak, Kunga Choephel, Yangdzom Lama, Losang Gyatso, Tenzin Dawa (Lettering in Tibet), Phuntsok Lhagyal, Tshedzom Tingkhye, Kalnor, Luguma, Tenzin Kunsel, Tenzin Rabten, and Rigzin Taring. The process of selection aimed to provide a wide range of interpretations of the theme of transcending boundaries from diverse perspectives, methodologies, and aesthetic languages. Furthermore, it was important to the collective to present a variety of mediums, and painting, graphic design, photography, collage, dance, and film were included in the show.

The artworks were inserted in the space in both thematic – societal, personal, geographical barriers – and visual clusters, without being fixed on creating a precise narrative the visitor had to follow. One of the major curatorial concerns when putting together the show was the political nature of the artworks in a Tibetan context. As the digital nature of the exhibition meant it was open to a much wider and international audience, conscious decisions were made about not putting overtly political works next to works produced by artists living in Tibet.

In addition to selecting artists and putting the show together, there were administrative and marketing duties to be fulfilled. After the exhibition was finally set up, the Yakpo Collective was concerned with its promotion and how to get people to visit a virtual exhibition. We circulated a number of promotional emails to museums and organizations related to Tibet. As the collective is still very young and not fully established among the Tibetan community or the contemporary art world, the bulk of its promotion took place on their social media. Two posters were created by the team: one main poster with details on the exhibition (Fig. 2), and a group of posters with the artworks of each exhibiting artist for them to publish and promote on their social media (Fig. 3). Two promotional videos in English and Tibetan were also published which explained the significance of the theme, the general layout of the digital space, and how to navigate it. All of Yakpo’s posts were shared by members of the collective, Tibetan, and art-related platforms, and on personal profiles.

The exhibition was launched on September 20, 2020. As part of my contribution to the exhibition, I wrote a blog post that was published on the Yakpo Collective’s website. For this project, I conducted interviews with some of the exhibiting artists to discuss what boundaries mean to them, and their experiences participating in a digital exhibition. Many of the artists, when reflecting on their involvement in the digital exhibition, emphasized how the digital format of the show presented them with the opportunity to transcend physical boundaries of isolation both geographical and mental and feel connected to a Tibetan community of creatives. Thus, the de-centralised nature of the internet permitted geographically dispersed people through social media to be introduced to each other, their work, and their networks.

It was a common feeling among the artists I interviewed that exhibiting beside artists from a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds served to both create a sense of shared identity and community and a place for everyone to reflect and define collaboratively on the development of Tibetan contemporary art. This engendered a distilled, world-creating environment for the Tibetan artists to inhabit. A part of this process is the collective’s role in creating a digital archive, a public resource of Tibetan artists and artworks. With the exhibition still visible on the website and I would argue, more importantly, its related posts on its Instagram page, the Yakpo Collective’s curatorial practices can control the trajectories of online circulation of Tibetan contemporary art and create a platform for Tibetan creatives to define a canon of their practice.

As shown, the experiences of the digital format of the exhibition revealed many positive aspects. However, in discussions with the members of Yakpo at the end of the exhibition, the digital nature lacked in its interactivity. Its format of an empty gallery meant that vising the exhibition was a solitary experience. McTavish argues that: “this isolation reinforces the notion that viewers should engage in singular encounters with artworks, focusing on them without distraction”.[ix] The consensus was that this limitation took away from the personal and emotional experience of visiting the exhibition. The lack of a connection with the physical works also affected the number of sales of the exhibited artworks. Thus, if on one hand, the digital produced a more intimate space for interaction and networking within the Tibetan creative community, on the other it negated an interactive exhibition experience and failed to produce revenue for the artists and the collective. As selling artworks is one of the main concerns of the collective who seek to help young Tibetan artists establish themselves and make an income out of their creative work, this was a major drawback.

To conclude, the data I collected while collaborating with the Yakpo Collective on the “Transcending Boundaries” exhibition raised many questions about digital curation, the role of social media, and the advantages and disadvantages it brings when discussing the art of geographically dislocated communities, such as the Tibetan community. With visitors from over thirty countries according to the analytics, the digital format of the exhibition made it possible for a much bigger and more international audience to come in contact with the Yakpo Collective’s project. The collective might still be young and not fully established whether in the Tibetan community or the art world, and it is difficult to ascertain its role in the grand scheme of Tibetan contemporary art however, I suggest that their use of social media is a fundamental step towards a collective storytelling of Tibetan experiences. This takes place through their collaborative approach as a collective. With everyone taking part in the curatorial decisions of the exhibition, the practice expanded and evolved beyond the conventional duties of a curator of selecting, organizing, and presenting artworks. In Yakpo’s case, a major component of the curatorial process was their significant employment of social media. Its main purpose might have been promotion, but the archival and public nature of Instagram has engendered the possibility of an explicit site of reconstruction for the Yakpo Collective to collaboratively narrate with the artists they platform their story of Tibetan contemporary art.

Finally, I would like to thank all the members of the Yakpo Collective for not only letting me be a part of this project but also for sharing their time and thoughts with me to discuss together their work and experiences as artists and as members of the collective.

Notes:

[i] Walton 2017: 151-152

[ii] https://www.yakpocollective.com/blog/tibetan-contemporary-art-the-new-wave

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] https://anti-materia.org/circumventing-the-white-cube

[v] Walton 2017: 161

[vi] https://www.yakpocollective.com/transcendingboundaries

[vii] https://artspaces.kunstmatrix.com/en

[viii] McTavish 2005: 232-233

[ix] Ibid. 233

Works cited:

McTavish, L. 2005. ‘Visiting the virtual museum: art and experience online’. In J.Marstine (ed.) 2005. New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell’s, pp. 203-225.

Walton, S. 2017. ‘Being there where?’ Designing Digital-Visual Methods for Moving With/In Iran’ in Salazar, N., Elliot, A., and Norum, R., (Eds.), Methodologies of Mobility: Ethnography and Experiment. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 148-171.

Wallerstein, W., 2018. Circumventing the White Cube https://anti-materia.org/circumventing-the-white-cube. (Accessed 14 February 2021)

The Yakpo Collective website https://www.yakpocollective.com/ (Accessed 14 February 2021)

Kunstmatrix website https://artspaces.kunstmatrix.com/en (Accessed 14 February 2021)

Isabella Cammarota has just completed her MPhil in Tibetan and Himalayan Studies at the University of Oxford.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities