ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

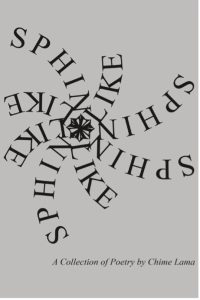

Sphinxlike

by Chime Lama

88 pages, 2024, $22.99, paperback

Finishing Line Press

Reviewed by Julie Regan

Modern Tibetan literature, which emerged in the contexts of cultural revolution and exile, has often rejected the Buddhist themes and aims of earlier genres of Tibetan literary works, using modern forms of poetry and fiction to extend the landscape of a free Tibet. Chime Lama’s Sphinxlike clearly aligns itself with this project of Tibet while also representing a fresh approach to the liberatory possibilities of Tibetan literature that reflects her unique background, including Buddhism.

Born neither in Tibet nor exile but upstate New York, where her father, Bardor Tulku Rinpoche, established a Tibetan Buddhist practice center, Chime Lama inhabits a new kind of Tibetan identity, which is also American. Many of the works in Sphinxlike wrestle with the problem of Tibetan identity from this further shore of exile she inhabits, as the title of the poem “Tibetan-American Anxieties” suggests. Yet others, such as “Capitalist Anxieties,” “Become a Ball, ” and “Thrill,” demonstrate the importance of a broad range of concerns that emerge in Chime Lama’s distinctly American context, such as the problem of money, the challenge of whiteness, and the thrill of new love.

Buddhist themes arise as a part of the ordinary life that is put under the lens of these poems. In “Bell of Cultivation,” for example, someone attempting to “look at the nature of the mind” chiefly recognizes, “I don’t know what I’m doing.” In “All My Pursuits,” each line in a list of seemingly altruistic accomplishments, including “having ‘studied’ the dharma,” is displayed as crossed out, except “all my pursuits have been selfish.”

Yet Sphinxlike is not ultimately interested in Buddhist answers so much as a kind of Buddhist method that challenges the poems’ characters – and its readers – to further questions.

As the title, Sphinxlike, highlights, this is not a book that will simply yield to interpretation. Chime Lama’s work is experimental in the best sense, which is to say that it invites the reader to try things, the way that the Buddhist teachers and experimental artists she evokes do. Her poems weave the Classical Tibetan she has learned as a translator, scholar, and practitioner into her English lines the way that Anglophone Tibetans in exile might mingle Hindi and colloquial Tibetan. And yet her Tibetan seed syllables scattered across the page, or organized in the shape of offerings, do more than create a sense of a Tibetan lived experience. They actively use Tibetan to shift the mind of the reader, in a way that hints at the power of such language in Buddhist contexts.

Lama also draws on her skills as a visual artist to create poems that invite her audience to read in new ways. The table of contents, for example, a spider’s nest of titles and page numbers in no particular order, suggests Lama is interested in provoking new ways of seeing more than helping readers find their way.

This shape-shifting continues in the body of the work. A poem in the shape of a circle-the-word puzzle seems to invite investigation, though its title proclaims “NO SECRETS HERE.” Meanwhile, concrete poems in the shape of diamonds or bells, or letters and lines exploding in all directions invite readers to find their own paths to the two (or more) truths they might reveal. For example, the poem that braids transcultural descriptions of a modern relationship (“My existence with you is beautiful. By that I mean sunshine rain in tokyo”) with traditional concerns of Tibetan Buddhism (“Will I give birth to a demon if I make love in the morning?”).

As if taking stock of her training as a scholar and a translator, Chime Lama sometimes hints at the possibility of interpreting the “sphinxlike” nature of a poem. For example, “Tibetan-American Anxieties: Wanting Sounds in a Barren Throat” plays with the scholarly apparatus of footnotes, which provide translations of the Classical Tibetan it includes. In another example, a poem composed of three Tibetan brackets containing the sounds of seed syllables is followed by a page of “Tibetan Concrete Poetry Annotations” to explain the traditional purpose of such syllables and what they do in this and other poems. While these details may add meaning, the fact that this seemingly explanatory page is also a poem complicates the Sphinxlike nature of the work, provoking further questions.

While some might find this kind of reading challenging, Chime Lama’s sense of humor and the playful quality of the work make Sphinxlike fun to read. Take the announcement she posts just before the first page:

Would the owner of the golden 1963 Peel P50 please move their car.

It is blocking the fire hydrant.

What is this about? The reader might ask, turning to the next page, only to encounter what appears to be a cute little creature, composed entirely of English and Tibetan punctuation marks.

Even more conventionally shaped poems don’t spell things out so much as invite the reader to explore tensions that must be experienced to be understood. “Talkie #1,” a kind of report on Tibet and Tibetans, for example, takes on the point of view of both insider (“Tibetans snore”) and outsider (“In Tibet there are dharma practitioners who really mean it.”), asserting clichés (“Tibet has many monasteries. Tibet has snow.”) as well as ominous contradictions (“Tibetan rivers drown people who cannot swim, and most Tibetans cannot swim.”)

Likewise, a poem titled “Summer in Tibet” is less the joyous homecoming one might expect than the challenge of taking on costumes and customs to gain access to a place where the narrator and her siblings “are not unwelcome.” While home in Woodstock is established “by divine decree” in “Talkie #2,” there are also challenges in finding a way to fit into American culture. As the “Old White female professor” in “Become a Ball” announces, “I really don’t think you have a place here.” “No one wants to read about your whatever-it-is culture.”

And yet Sphinxlike exposes the fallacy of such a statement by its very existence. Its publication by Finishing Line Press, not to mention the prior publication of dozens of its poems in a wide variety of literary journals, indicates that Chime Lama’s work is already being read by the wider audience the professor seems to deny, not to mention the significant audience of Anglophone Tibetans, Tibetan Buddhists, and scholars of Tibetan literature. It’s almost as if Chime Lama took the challenge to present that “whatever-it-is” that is her own Tibetan culture in all its complexity. For this is what her rejection of narrower interpretations in Sphinxlike allows her to accomplish.

Julie Regan is a scholar/practitioner of both Buddhism (Harvard University, PhD) and Literary Arts (Brown University, MFA). She has taught courses on Literature, Creative Writing, Buddhism, and Meditation at universities, including Hunter College, NYU, and La Salle University. Her short fiction, essays, and articles have been published and anthologized in literary as well as academic journals and books.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities