ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

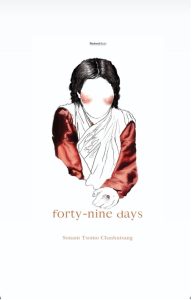

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang’s Forty-Nine Days of Bardo

Tenzin Dickie

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang is a Tibetan poet who writes in Tibetan, English, and Hindi. She has a degree in creative writing from Miami University. Her works have been published in Newtown Literary, Bridges (Villanova University), in a special issue of Cadernos entitled “Testemunho poético de tibetanos no exílio” (“The Poetic Testimony of Tibetans in Exile”) as well as Khabdha and TibetWrites. She was born and raised in Bir, Himachal Pradesh, India. Her debut poetry collection forty-nine days was published by Blackneck Books in November 2024. This interview was conducted over email in the fall of 2024.

Tenzin Dickie: Your debut poetry book forty-nine days is coming out from Blackneck Books later this year. I love the way you thought about this book and conceptualized it. Please tell us more about this book, and how this collection came about.

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: To be honest, I didn’t think this would turn into a poetry collection. The collection is about the forty-nine days of bardo after my mother passed away. When my mother passed away, I was in this uncomfortable/unfamiliar place where I didn’t know what I was supposed to do as my mother’s daughter. It was only me and my thought(s), and the only thing I knew to do was to write them down as each of the forty-nine days passed. I was writing the poems for myself—to see on paper what my feelings were during this very difficult time in my life. I want to thank Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, you, and Bhuchung D. Sonam for pushing me to finish this collection.

Tenzin Dickie: I know this book took you a long time, and you struggled with the writing because it’s a very painful subject. What were your struggles with the book and the material? What gave you the strength to write it and finish it?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: I wrote this book initially for myself. I didn’t revisit it for a long time because maybe a part of me wasn’t ready to face reality. Whenever I sat down to edit these poems, it was extremely difficult and I couldn’t really do it, since the pain was raw and a part of me felt guilty for not being there with my mother during her final days. As a community, I also feel as though most of us struggle with expressing our feelings and love to our loved ones.

The forty-nine days after my mother passed were the longest forty-nine days of my life. Somehow, the days just stretched into heavy nights and the nights never ended for me. After forty-nine days, I could finally see the light. Now, years later, it is still painful to return to these poems, but I am more accepting of the loss and know that there are many things in life out of our control; death being one, I am more at peace now and accept life and all its vicissitudes with a new sense of calm. But I miss my mother every single day. I also hope that anyone who lost a parent can find a sense of calm in my poems and learn that we all grieve and cope in different ways. We are all learning to be more human by going through these changes and pain.

Tenzin Dickie: Can you share one of your poems from the book?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: Sure, I am happy to. I was still going through the process of grieving and trying to make sense of the loss and what it felt like to be a daughter without a mother for the rest of my life, and as I got on the train, I saw this elderly Tibetan woman who reminded me so much of my mother. I wrote this poem on the train, talking to my mother in my mind.

This elderly Tibetan woman

Sat beside me on the R train

Her fingers on the rosary rotating

Reminded me of my mother’s hands.

She stared at me for a minute too long

I could see her from the corner of my eyes

Her eyes looking to find something familiar

She must have left behind—

My mother was the exact height as hers

She even had wavy hair like my mother

I wanted to say Tashi Delek to her

But ended up not saying it.

I can see her smile

In the window on the subway cart

In that moment, I felt what it would feel like to be riding the subway

With my mother.

Tenzin Dickie: You are that rare poet who writes tri-lingually, in English, Tibetan, and also Hindi. I think it’s amazing that you have enough mastery in three languages to write poetry in them. How do you choose what to write in which language? Can you speak to the experience of writing in different languages, and what that means to you?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: Ha ha! It’s not like that at all. I am blessed enough to know these languages, but I haven’t mastered anything yet. Whenever I think of a poem, whatever language it comes to me in, I write in that. I don’t like to translate my poems because I feel they lose the beauty of the language they were originally written in, with all its nuances. I think each language carries different meanings with certain words and often times when a word gets translated, it loses the very essence of that word in the previous language.

Tenzin Dickie: What art forms shaped you while growing up?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: Growing up in India, I think I was very influenced by Bollywood movies and music. In boarding school, I always loved reading stories; English, Tibetan, and Hindi used to be my favorite subjects. I used to write song lyrics and read them over and over again, but as I started to gain a sense of my own likes and interests, I felt very drawn to visual art. I love watching movies, especially ones with a good script. Recently I watched Past Lives, and the writing was brilliant. There are lots of good Korean movies and dramas that I feel are quite poetic in terms of the writing and the cinematography.

In India, I also read lots of Tinkle comics and short stories. At present, I read different writers and poets. Some of my favorites are Li-Young Lee, Rainer Maria Rilke, Gendun Choephel, Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, Kazuo Ishiguro, Gulzar Saab, and Lilly King. I often read many writers, and each writer has different things to offer; so I am always learning.

Tenzin Dickie: On your social media handles, you call yourself a poet under construction. Can you tell us more about the construction of your poet self, and what that means to you?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: I feel like I am under construction all the time. I feel so many things whether it’s love, heartbreak, laughter, joy. To be honest, I never thought of myself as a poet. I just find it easy to write words down to express myself best but since we live in a world of ‘titles,’ I guess I am seen as a poet. However, I simply consider myself as someone who likes to write; It’s as simple as that. But I must say that sharing your writing with everyone is the most vulnerable thing you can do to yourself. Especially with this upcoming collection, I feel like my heart is in my hands for everyone to see.

Tenzin Dickie: I also wanted to ask a question about moving from India to America, and getting used to your new life here, as a refugee and immigrant. What did you think of America? And what does that have to do with literature?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: I never had any plans to come to the States but thanks to a scholarship, I was able to go to college here and get an American education. Whatever I thought America was from the movies I watched growing up, when I arrived in Ohio in the middle of nowhere, it was so very different. I cried the first few weeks since I was by myself and very lonely but eventually it got better. As a refugee and an immigrant, I was constantly trying to fit in. I felt lost during the first semester but slowly adapted to the new environment. I had so many first-time experiences. I don’t want to think about the sad stories, but I will tell you a funny thing. When I first arrived here, I had no cell phone, and I wanted to call home, so I walked around the area and saw this gas station. I went in and the guy at the counter asked if I needed any help. I asked if he had STD… he looked shocked and said “No!” I stepped out and didn’t think anything of it. Months later, I realized what that meant. In India, we had STD phone booths— STD stands for Subscriber Trunk Dialing—with the word STD written on the outside of the booth. So, every time I think of this incident, I still laugh.

Tenzin Dickie: Your day job is at Tenzin Wangyal’s law firm, the go-to law firm for Tibetan immigrants in the US. What does this job teach you about life and art?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: As stressful as the nature of the job is, I feel rewarded when a case gets approved. This is my way of perhaps contributing to Tibetan society. And as a Tibetan, I think working at the law firm magnifies even more all the issues we face as stateless Tibetans with no proper documents such as marriage, birth, or death certificates, and our problems with the discrepancies with our names, or not having surnames and having to deal with all the FNU(S) NNG, LNU, NGN designations that the US embassy and or the USCIS would issue us. It’s so clear to me that the nature of our being and our citizenship is always called into questioned.

Tenzin Dickie: Maybe it’s too early to ask you, but I want to know. What’s your next project?

Sonam Tsomo Chashutsang: I have two projects lined up. I have a few poems already for the next book. It’s a collection of poems about people in Bir that I have known growing up but who already passed away; so each poem is titled after their names. Another project I am working on is with my friend Kesang, who did the beautiful cover for my book. Hopefully, these projects will come to fruition soon.

Tenzin Dickie is a writer, translator, and editor. She is Yeshe journal’s Interview editor.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities