ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Remediating Uncle Tonpa: The Lives of a Tibetan Trickster in the People’s Republic of China[1]

Timothy Thurston

Abstract: In recent years, remediation—appropriating the techniques, forms, and social significance of other cultural forms in a new medium (Bolter and Grusin 68)—has provided indigenous and minority cultural producers around the world with a valuable way to connect traditional knowledge with emerging art forms. Narratives about tricksters in particular have figured prominently in this process, as they seem to simultaneously entertain their audiences and speak to the marginal conditions that many indigenous communities currently experience. One such figure is the Tibetan trickster Uncle Tonpa. Uncle Tonpa impregnates nuns and makes fools of nobles. He swindles the wealthy and gives to the poor. For the majority of Tibetan history, narratives about Uncle Tonpa’s exploits have circulated among Tibetan communities primarily in oral form. In recent years, however, tales about the Tibetan cultural hero have found new life in emerging media portrayals. During the Maoist period, Uncle Tonpa was drafted into the service of the Communist Party, which saw tales of the trickster’s egalitarian economic ethos as proof of a nascent Tibetan class-consciousness. However, since the 1980s, Uncle Tonpa has inspired authors and budding filmmakers in China’s constrained media climate. This paper examines how the remediation of traditional narratives reveals the trickster’s continued relevance for both governmental and vernacular attempts to influence the ongoing negotiation of Tibetan regional and ethnic identities in China.

Keywords: Trickster, Uncle Tonpa, Remediation, Tibetan folklore

Introduction

Trickster characters from cultures around the world—such as Native American tricksters Raven and Coyote, the Norse Loki, the Greek Hermes, Reynard the Fox from Western Europe, and West African trickster Kweku Anansi—have long intrigued folklorists. But these characters have entertained communities for far longer. Their simultaneous existence on the margins of society and their centrality to society defy easy explanations. Much North American study on tricksters examines the nature of the trickster characters that draw heavily on Native American folklore traditions. Radin views trickster tales as an “outlet for voicing protest against many often-onerous obligations” (152). Meanwhile, Babcock-Abrahams draws from Victor Turner’s concepts of liminality to argue that Trickster’s capacity for social inversion also holds the potential for reflective creation and, particularly, the creation of communitas (184-185). In these perspectives, Trickster offers productive possibility through negating what already exists. Ballinger critiques the suggestion that Trickster lives on the margins, concluding instead that “in spite of himself, Trickster encourages us to see the world through the collective social eye and thus to see beyond the individual self” (28). Simultaneously central and marginal, then, trickster narratives both defy and define. They serve the community both through inverse example and through imagining the world anew.

Tibetan oral tradition boasts a host of cultural heroes who sometimes resort to trickery in order to accomplish their goals. These heroes include out-and-out tricksters like Uncle Tonpa (T, a khu ston pa)[2] and Nyi chos bzang po,[3] buffoons like A rig glen pa, and devout warriors like Klu ‘bum mi rgod and King Gesar (both of whom may also use trickery to achieve their conquests). From among these many tricksters, Uncle Tonpa is arguably the best known (Kun mchog dge legs et al. 6). Indeed, if you spend enough time in, or reading about, Tibetan communities, you will inevitably learn about Uncle Tonpa, the legendary trickster who uses his wits to swindle and sleep his way through Tibetan society. For example, you might hear a friend tell stories about how Uncle Tonpa made a king bark like a dog, how he tricked a merchant off his horse, or how he was discovered in a nunnery after its residents began turning up pregnant. I have often heard young Tibetans—while together in school dormitories or when out with their friends—describe hearing Uncle Tonpa stories. Almost all are familiar with at least one of his exploits.[4]

While Orofino (Orofino, 105-7) traces the origins of Tibetan trickster tales to ancient Greece and Egypt, Tibetans generally accept that Uncle Tonpa was either a single historical figure (Ra se dkon mchog rgya mtsho, 92-96) originally from Central Tibet, or a ”theme-nickname” for the exploits of any number of quick-witted figures in history (Löhrer, 2). Though Tibetans across the plateau tell these stories, they are told most widely in Central Tibet.[5] In the 1960s, after centuries of oral transmission, Tibetan and Chinese intellectuals began to create textual versions of the tales, and several were published in the ensuing decades.[6] After decades of such publication, you are now much more likely to come across Uncle Tonpa in bookshops, where you may find a thin paperback or two detailing the trickster’s exploits. Some children’s sections even feature illustrated editions aimed at young readers. A far greater number of publications are out of print or hidden within larger volumes on “folk literature.” A search for Uncle Tonpa on the Tibetan search engine Yongzin.com brings up a number of hits, including links to a CGI cartoon series aired on Tibet television in 2018 (Ch, Xizang dianshi tai), an undated comic book series that tells the story of “Young Tonpa” (Chen), a 2021 music video from the sensational pop duo Anu, and a restaurant named after the cultural hero.[7] The proliferation of such Tibetan media from outside the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) also indicates that the trickster, and oral traditions more generally, have become important factors in political and intellectual discourses about socialism, heritage, and nationalism in contemporary Tibet.

What, then, happens when oral traditions are reimagined in new media? What social processes, contextual factors, and social actors contribute to this “remediation” of oral traditions? And how does this remediation of the Tibetan trickster tradition help us understand the changing spaces for the display of Tibetan cultural traditions in contemporary Tibet? To answer these questions, this article explores a variety of media related to Uncle Tonpa. These works are all produced outside the TAR and include a publication of traditional oral versions of Uncle Tonpa stories sponsored by the PRC government, a short story by Sinophone Tibetan author Alai, and a little-known film by director Klu rgyal rA ti. These media are selected for convenience, but also because they demonstrate the variety of stakeholders involved in remediating traditions, and the different ways they use trickster tales in their work.

Remediating Trickster

Whereas much previous research focuses primarily on the content of trickster narratives—with the trickster forwarded as a cultural hero who may be a “selfish buffoon” (Carroll, 106) or a clever hero (Klapp, 21)—and their function in traditional communities, Vizenor argues that the “trickster is a sign, a communal signification that cannot be separated or understood in isolation” (Vizenor 189; cf Squint, 107). Studying Trickster solely along the question of plots and Jungian archetypes, then, is not enough. Instead, tricksters must be studied diachronically and dialogically with attention to, for example, events, media, and audiences as part of a broader ongoing cultural phenomenon.

Vizenor is primarily interested in the interplay between oral and literary traditions. And yet, the proliferation of affordable digital technologies has brought new means of expression to these traditions, and many indigenous cultural producers now re-create their traditions in digital media. In particular, cultural producers often deploy Trickster narratives in their media creations. For example, Hearne (98) writes about Cherokee groups who produced the clay animation film The Trickster (2003). Other indigenous directors have also mobilized trickster narratives in new media creations to preserve vanishing narratives, and to transmit cultural knowledge to a new, media-savvy generation. When native, indigenous, and minoritized cultural producers deploy the techniques, forms, and social significance of traditional tales in new media, they engage in acts of remediation (Bolter and Grusin 68).

The decontextualization of traditions, and their recontextualization in new media—as happens in remediation—also constitutes an act of control over traditions (Briggs and Bauman, 148). Additionally, remediation mobilizes the “affordances” of different media—the qualities of different media that render different actions or experiences possible—to reach broader, multilingual audiences that extend beyond the immediate event of the storytelling performance. This combination makes remediation a powerful tool for a variety of actors.

Governments and other powerful groups may remediate traditional materials for power, profit, and propaganda by shaping the contexts and content of appropriate expression, as we will see below. On the other hand, when indigenous cultural producers remediate tricksters, it may be an act of cultural healing and wresting back control over their own narratives. In this way, remediation provides a valuable tool for understanding how communities produce locally meaningful cultural phenomena under the influence of globalization (Silvio, 286) and dispossession. In illiberal contexts, native indigenous cultural producers often must harness trickster energy themselves as they navigate the ever-shifting constraints imposed on the language and contexts of remediated material, and access to the means of media production.

Government Remediations

In the years after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Uncle Tonpa was drafted into the service of promoting the new communist government’s policy goals. This undertaking was in accordance with Mao’s famous dictum from his “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art”: that all art and literature must “serve the masses.” In this climate, Uncle Tonpa’s egalitarian ethos was seen as proof of a nascent Tibetan class-consciousness. But this conclusion is only the result of considerable “processing,” defined as “the process by which some versions of stories are transcribed, translated, edited and released in print or electronic format” (Bender 232). This process frequently involves considerable compromise, amendment, and re-working, so that the final texts may appear quite different from the unique and emergent versions performed for specific audiences and in specific contexts. The introduction to one early collection of Uncle Tonpa stories—published in the 1980s by the Sichuan Province Folk Art Research Association (Ch, Sichuan sheng minjian wenyi yanjiu hui) —demonstrates how trickster texts had to undergo significant processing in both form and content before being deemed appropriate for publication in the PRC. This introduction, purportedly written in 1963, shows that processing addressed both the form and the content of the stories.

The introduction to this collection states that the editorial team worked with the support of cultural offices in Aba (T, rnga ba) and Ganze (T, dkar mdzes) prefectures to record over 300 tellings of Uncle Tonpa stories between 1961 and the writing of the introduction in 1963.[8] When tales overlapped, the editors write:

Regarding the same story told differently, when editing, we generally selected a comparatively complete version as the core, taking from the long to complement the short, enriched it through polishing; we also selected relatively complete versions for publication as independent pieces.

对于说法不同的同一故事,整理时,我们一般是选一种较为完善的说法为核心,截长补短,丰富加工;也有就选一种较为完善的说法独立成篇的。(Sichuan sheng 6-7).

In this way the editors narrowed 300 stories into 48 Chinese-language “complete” (Ch, wanshan) or “ideal” texts.[9] For some stories, editors recorded a combination of the names of the storytellers, collectors, and translators, but provided no further record of editorial decisions, nor any record of how tellings varied from one to the next. Additionally, the editors omitted Tibetan versions of the stories, and it appears that processing and translation flattened much of the flavor of Tibetan traditional speech—often full of double negatives, repetition, and nuance of evidentiality—into a number of short clauses that lack the expressiveness of the original.

To be worthy of publication, it was not enough to be an ideal text shorn of the more ribald material that forms a crucial part of the Uncle Tonpa character. Instead, collection, processing, and publication had to serve political goals, especially in the context of the Maoist period—when the tales were collected—and the early post-Mao period, when the collection was published. The introduction repeatedly emphasizes the revolutionary nature of the stories, as shown by the following quote suggesting that, taken together, Uncle Tonpa stories:

Express the irresolvable contradiction between the rulers and the ruled, the serfs and the lords; they reflect the suffering Tibetan peoples’ desire to break their fetters, to liberate themselves, and the unstoppable desire for a better life. The loves and hates of their class are completely clear.

表现出统治者和被统治者,农奴和农奴主两个对立阶级不可调和的矛盾;反映出苦难的藏族人民渴求打破枷锁,解放自己, 向美好生活的不可抑制的愿望, 阶级的爱憎是十分明显的。(Sichuan sheng minjian wenyi hui 3).

A reader more familiar with the Uncle Tonpa tradition may recognize that the editors reached this conclusion only after they excised all of Uncle Tonpa’s lascivious exploits and focused on only those stories that seem to reveal Tibetan class consciousness.[10] In this way processing and remediation also sanitized this collection of folktales in order to create a trickster who evidenced an anti-religious and class-conscious Tibetan ethnic group ready to serve revolutionary purposes during the Maoist period.

Through translation and textualization, this Chinese publication also broke the bonds of immediacy and emergence that are central to oral performance and made these traditional narratives available to new audiences. Uncle Tonpa was no longer in dialogue with only Tibetan audiences, but with a constellation of trickster legends from across the new Chinese nation. Similar state-sponsored collection and publication work encompasses other ethnic minority trickster characters such as the Uyghur Effendi (Ch, Afanti), the Miao epic hero Jang Vang, and the Da’ur Menggongnenbo. As Bauman and Briggs (148) write, removing an oral traditional text from its original performance contexts (decontextualization) and performing it in new contexts (recontextualization) is an attempt to exert control over the tradition; remediation asserts that the remediating agents have the right to speak the tradition. In the case of state-sponsored remediation of trickster tales, the act of crossing media from the oral medium that largely remains beyond the scope of state control to the print medium over which the state exercises tight control plays an important role in defining the corpus of folk literature within China’s borders.

Alai’s Uncle Tonpa in Sinophone Literature

In addition to government entextualizations, textual versions of cleaner Uncle Tonpa stories also feature in language textbooks aimed at foreign learners of Tibetan (Goldstein et al. 178-181) and Tibetan students of the English language (Tshe dbang rdo rje et al. 43-45). Picture books depicting some of the trickster’s exploits follow similar trends: displays of wit to temporarily upend the traditional Tibetan social structure and to get money and food for the powerless. Well-established authors of more serious modern literature, too, may choose to write about these sanitized exploits.

While government remediation controls Tibetan folklore tradition for the purposes of the state, government support for collecting and publishing trickster tales (and other forms of Tibetan oral tradition) also authorizes Tibetan cultural producers to creatively intervene in their traditions. In an otherwise restrictive cultural field, Tibetan cultural producers find in tricksters a character whose less ribald exploits provide both a valuable lodestone of Tibetan culture and a safe topic for publication.

Sinophone Tibetan author Alai, in particular, has drawn inspiration from Tibetan trickster narratives, embedding them in several works throughout the course of his creative career. Alai even devoted one of his early short stories entirely to a portrayal of Uncle Tonpa. Alai’s Uncle Tonpa is serious and angry. He is born into a landlord’s family but becomes an outcast after his abnormally large head causes his mother to die in childbirth. The early experience of rejection, and an ensuing hatred for those in power, seem to motivate his tricks.

Alai’s short story includes several famous episodes from the corpus of this legendary trickster’s exploits. At one point, Uncle Tonpa convinces a merchant to hold a pole up in the middle of Lhasa while he escapes with the merchant’s wealth, an account recorded in at least one other collection of Tibetan folktales (Sichuan sheng 84-86). In a second important episode, Uncle Tonpa steals Tibetan momo (T: mog mog) dumplings from a group of monks. In another version of this episode, Uncle Tonpa travels with four merchants, and the five of them must split cakes of tsampa (a traditional Tibetan barley-based food) among themselves. Uncle Tonpa convinces them to each split their cakes in half, and to give him half and take half for themselves (Sichuan sheng 167-8). In the end, Uncle Tonpa wins half of the food, while his dupes are each left with only half of what they started with.

In these episodes, Alai reaches into what Lauri Honko (18) calls the “pool of tradition,” the “‘pool’ of generic rules, storylines, mental images of epic events, linguistically preprocessed descriptions of repeatable scenes, sets of established terms and attributes, phrases and formulas which every performer may utilize in an imaginative way.” If the pool of tradition provides the source for some of the materials in the story, Alai also creatively imagines many other parts of the trickster’s character and his life.

Alai’s interest in the trickster is ongoing and appears in several of his published works. In his acclaimed novel Red Poppies, Alai’s mentally impaired narrator speaks of the trickster and culture hero Uncle Tonpa in passing (The Dust Settles). In his novel on the Tibetan epic hero, King Gesar, Alai, in an unprecedented move, even finds a place for the legendary trickster in the Tibetan epic (Gesaer wang).

In Alai’s signature work The Dust Settles (Ch, chen’ai luoding) —translated by Howard Goldblatt with the title Red Poppies—the main character is generally thought to be mentally impaired, but this character’s simple wisdom places his family among the most powerful of the Rgyal rong kingdoms until the People’s Liberation Army arrives. In a translator’s note, Howard Goldblatt and his partner Sylvia Li-chun Lin draw an explicit link between the idiot narrator and Uncle Tonpa, noting that Alai views “wisdom masked by stupidity” as a characteristic of both Uncle Tonpa and of his novel’s protagonist (Red Poppies). This portrayal of Tibet’s most clever and irreverent trickster as a simple person who occasionally wins a hand emphasizes perceived Tibetan marginality and backwardness. Notably in Red Poppies, the narrator’s simple wisdom is effective within Tibetan space but is powerless in the face of the Chinese state. And in Alai’s Song of King Gesar, the eponymous hero of the Tibetan epic seeks out the impoverished Uncle Tonpa and dialogues with him for a period of time, though the two ultimately walk very different paths. Though interesting to imagine how the two might interact, ultimately, there is little Uncle Tonpa can do at the cosmological level on which Gesar operates.

Alai’s continued references to the trickster are striking. When I asked Alai about his continued affinity for Uncle Tonpa during a conversation in 2010, he stated:

He is a pauper. He struggled with the wealthy, and then he won. And he’s powerless, he struggled with powerful people—kings, leaders—he struggled with them, and he won again. Moreover, the methods he uses are the part that makes folktales interesting…you look at the ways he wins, they are all special characteristics of folktales. The ways he wins aren’t complicated at all. I think that this basically represents the wishes or hopes of the folk. Actually, it also represents a type of folk wisdom.

他是个没有财产的人,他就跟有财产的人斗,然后他胜利了,然后他是没有权利的人,他就跟有权利的人:国王啊,领主啊, 跟他们斗,他又胜利了。… 而且你看他胜利的方法,… 它就是民间故事的特征。他胜利的方法一点都不复杂。…我就觉得这个差不多就代表,民间的这样一种期待或者一种民间的希望,其实也代表一种民间的智慧 。

Alai writes for a Chinese-speaking audience. In his capable hands, then, Uncle Tonpa stories are no longer the stories Tibetans tell themselves about themselves. Rather, the Sinophone Uncle Tonpa translates something that is undeniably Other to a national, and even international, audience. Alai’s Uncle Tonpa tricks his opponents but is neither irreverent nor funny. He is serious and angry but poses no threat to social order.

In portraying Uncle Tonpa as such, Alai fails to engage with Tibetan audiences. However, his defense of Tibetan intelligence and hope also refuses Chinese state discourse that emphasizes the “latent class sentiment” encoded in Uncle Tonpa narratives. Perhaps, then, Alai—who is half-Hui and half-Tibetan and hails from the Rgyal rong region on the periphery of the Tibetan cultural region—draws inspiration from the trickster character both to serve his writing and to help him negotiate his own controversial place as a Sinophone Tibetan author who is marginal to, and stuck between, both Tibetan and Chinese cultural worlds. Alai’s Uncle Tonpa allows the author to revel in his own marginal space and bolsters his own claims to present Tibet to Chinese audiences.

Uncle Tonpa, the Movie

So far, I have focused on remediation of Uncle Tonpa stories into print, but as Tibetans began to create and consume audiovisual media in the 21st century, cultural producers brought Uncle Tonpa into these new media as well. Claymation and animated versions of trickster tales introduce some of the trickster’s less risqué exploits to young audiences. There also exists at least one feature film made for all ages simply entitled “Uncle Tonpa” (Klu rgyal rA ti). This low-budget live-action film — released directly to DVD in 2014 and sometimes found in local media shops — is unique in how it combines traditional narrative, a novel narrative, and the director’s own artistic vision.

In the opening scene, Phuntsog, a local noble, comes across Uncle Tonpa as the latter pretends to nap in the grasslands. When the noble berates the trickster for being an idler, the trickster “wakes up,” apologizes, and talks about a beautiful woman in his village who could become the nobleman’s ninth wife. Phuntsog’s anger fades as his lust grows, but when Uncle Tonpa teases the noble for how many wives he has, Phuntsog becomes cross, dismounts, and chases the rascal. When the noble sits on a stone in order to catch his breath, he finds that Uncle Tonpa has glued him to his seat. When he stands up, his pants rip, exposing his backside to the elements.

After this initial trick, Uncle Tonpa works with a number of local people to stand up to the ridiculous demands of local nobles (one noble asks a man to get milk from male yaks, thereby also demonstrating his ignorance of pastoral lifeways), helps unite lovers, and cons a renowned warrior out of his horse and clothes. The film depicts several other of Uncle Tonpa’s famous tricks on a small cast of powerful opponents. But instead of treating each episode as self-contained, as often happens in the folktales, the film links many of the trickster’s exploits into a sequence of mutually supporting tricks. For example, when Uncle Tonpa tricks the warrior into giving up his horse and clothes, he gives the horse to Master Phuntsog as a wedding gift. Thereby excused from the wedding, Uncle Tonpa dresses as the bride so that the real bride can elope with her true lover. Additionally, while traditional Uncle Tonpa tales pit him against a generic group of leaders, Uncle Tonpa’s chief adversary throughout the film is a single, named character: Master Phun tshogs.

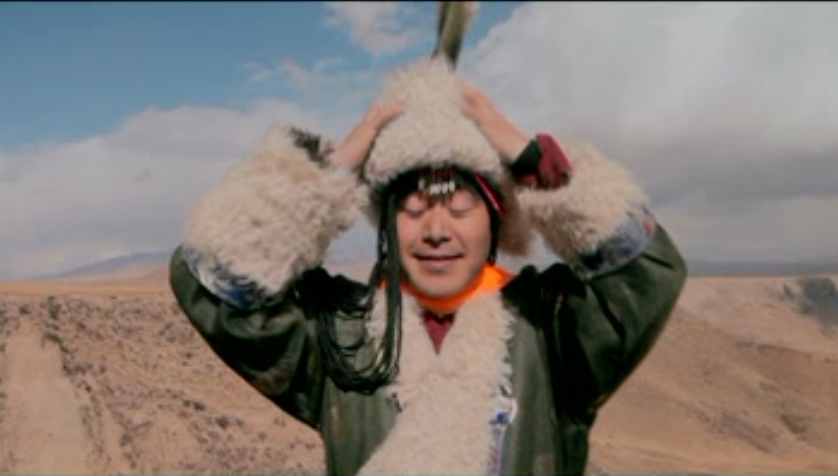

Figure 1: Uncle Tonpa dresses as the bride.

The film’s director, Klu rgyal rA ti, is an avid, but little known, filmmaker who works outside the more famous coterie of Amdo Tibetan filmmakers around Pad ma Tshe brtan. He hails from Bis mdo in Amdo, part of Qinghai Provinces’s Xunhua (T, ya rdzi) Salar Autonomous County. He directed this film as a recent graduate of the Beijing Film Academy and has written or translated several books on filmmaking into Tibetan. Though neither this film, nor any of his subsequent work, has previously featured in International Film Festivals — or been the topic of international scholarship — he has cut out a niche directing his own films and working with local governments in hopes of creating popular films that audiences will enjoy.

A few months after the film was released, I met with Klu rgyal rA ti to discuss his work. He confessed that his inspiration for the film came from a recognition that there was never enough Tibetan material to watch during the Tibetan New Year period. While there were television dramas based on folktales—namely Zhi bde nyi ma’s Pig’s Head Soothsayer (T, mo ston phag mgo)—there were no feature films in this category. Klu rgyal rA ti hoped that his film would fill this gap.

He then needed to write a script with a sufficiently compelling narrative. This task proved more difficult than he initially expected. He began with two different versions: one that he described as a “Mtsho sngon” (Qinghai Province) Uncle Tonpa, and one from the Tibetan Autonomous Region’s Nationalities Publishing House (T, bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang). Though he provided no further identification for these versions, he said that he found the former to be insufficient, so he selected to adapt the script from the version of Uncle Tonpa stories published by the Tibet Nationalities Publishing House. Note that although Klu rgyal rA ti is from Amdo, he preferred a version of the stories that comes from Central Tibet. This decision, however, presented its own issues; the written version was heavily literary (T, rtsom rig gi rang bzhin shugs che gi), emphasizing description and narration over dialogue. Additionally, the individual episodes were stand-alone stories. This combination made the stories ill-suited for a feature-length film and necessitated significant adaptation and interventions to link the episodes and add needed dialogues.

By the director’s own estimation, the script is about 40% of his own making, and the remaining 60% comes from the written stories. Within that 40%, Klu rgyal rA ti intervened in three areas. Firstly, he feels that film’s “way of telling the story” (T, gtam rgyud gyi brjod stangs) should emphasize conversation, whereas literary and oral versions often spend more time narrating situations and activities. Secondly, he created a plot that links the individual episodes into a broader story, adding names and identities to Uncle Tonpa’s opponents, and having some of them become the object of multiple tricks. Finally, he changed Uncle Tonpa’s location: whereas the stories frequently seem to take place in farming areas, the director placed his film in a pastoral area, because pastoral areas are “a characteristically Tibetan environment” (T, bod gi khyad chos gi khor yug).

The affordances of the filmic medium allowed Klu rgyal rA ti to imagine and tell the trickster’s stories in new ways. The composition and editing of different scenes, for example, helps to support the trickster’s inversion of social norms. In the first scene, for example, when the noble sits on his horse, low-angle shots emphasize the social and physical distance between Uncle Tonpa and the portly elite (see fig. 2). Once the noble dismounts, however, he enters Uncle Tonpa’s domain. When the noble chases Uncle Tonpa into a sunken bit of the grassland and struggles to climb out, the camera aims upward at the trickster as he teases the fallen noble (fig. 3).

Figure 2: Low angle shot of the elite “sku ngo phun tshogs’ berating Uncle Tonpa.

Figure 3: Uncle Tonpa turns the tables as Sku ngo phun tshogs scrambles after him.

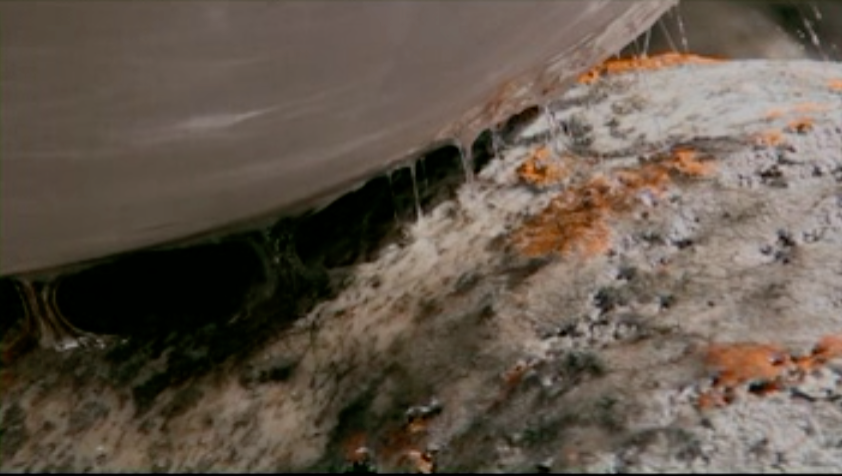

After teasing the portly master, Uncle Tonpa sits on a rock and daubs some clear material on it from a bowl that he pulls from the fold of his robe. Extreme close-ups show Uncle Tonpa pull the bowl out of the pocket of his robe and daub the clear material on the rock.

Figure 4: Uncle Tonpa daubs adhesive on a rock.

When the noble finally reaches the rock, Uncle Tonpa has already left. The local elite needs to catch his breath and takes a seat but finds himself stuck to the rock. Accentuating the absurd situation, another extreme close-up shows the noble straining to pull himself away from the rock. When he finally stands up, the pants rip, exposing his backside to the elements.

Figure 5: Sku ngo Phun tshogs finds himself stuck to the rock.

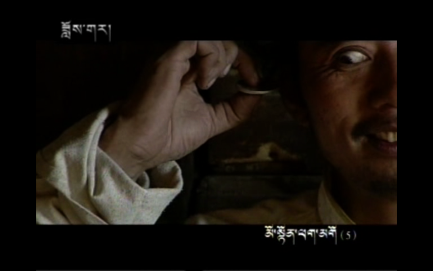

Throughout, the film uses close-ups and mid-length frontal shots when individuals speak directly into the camera. The camera does not linger on any of these moments; Klu rgyal rA ti avoids the sort of static long shots and documentary aesthetic for which Tibetan arthouse films by Zonthar rgyal and Padma Tshe brtan are famous (see, for example, Grewal). Even scene-setting shots rarely last more than a few seconds. Instead, the director frequently switches camera angles to focus on the speech, activities, and expressions of different characters. These visual strategies mimic the comedic language used in Tibet’s other major folktale-inspired Tibetan comedy: The Pig-Headed Soothsayer (T, Mo ston phag mgo), featuring the renowned comedian Zhi bde nyi ma. In particular, both films use extreme close-ups to create humorous effect. While arguably no other Tibetan actor can compare to Zhi bde nyi ma for physical comedy, the images depicting Uncle Tonpa rubbing adhesive on the rock (figure 4) and Phuntsok’s buttocks adhering to the rock (figure 5) are reminiscent of the extreme close-ups of Zhi bde nyi nma’s wastrel-turned-soothsayer (see figure 6 below).

Figure 6: Extreme close-ups of Zhi bde nyi ma’s face in “The Pig’s Head Soothsayer.”

In these ways, Klu rgyal rA ti’s film version of the tradition involves a double remediation: the legends are first published in written form, which in turn becomes the basis for re-telling as a feature film. While Chinese-language versions discussed above may make the tale available to Sinophone audiences, Klu rgyal rA ti’s film version avoids such steps. Rather, he creates only Tibetan language versions and goes out of his way to leave no doubt that the story takes place in Tibetan space. The only evidence of the broader Sinophone world is in the unclear, extradiegetic Chinese subtitles flitting across the bottom of the screen. Nevertheless, the influence of earlier remediations remains. For example, Klu rgyal rA ti emphasizes the trickster’s less ribald exploits. The director even avoids depicting tricks that target monks because the direct portrayal of Tibetan Buddhism (even a satirical portrayal) remains difficult in the PRC. Klu rgyal rA ti can speak back to a Tibetan audience, and even intervene in the traditional storytelling, but only within the state-imposed limits of acceptable cultural expression.

Conclusion

Across the world, remediation has become a powerful tool for different actors to control the representation of traditions and the groups that have sustained them. But these remediations themselves serve a variety of ends for the people participating in their production, and for the audiences to whom they are directed. In this article, I have discussed three different “remediations” of Uncle Tonpa coming from the Sino-Tibetan border regions of Amdo, Kham, and Rgyal rong, and how various cultural agents have deployed Uncle Tonpa stories in different media. These three examples are representative, rather than an exhaustive catalog of the remediations and entextualizations of Tibetan trickster narratives; they demonstrate just some of the ways that different stakeholders have used trickster narratives to their own ends. I have suggested that government-sponsored remediations have narrowed the range of possible expression, but that later remediations by Alai and Klu rgyal rA ti demonstrate how Tibetan cultural producers manage to find in tricksters the means to reach a variety of ends.

However, these efforts do not stop at trickster narratives. Official approval of the Tibetan epic of King Gesar, for example, has authorized the continued retelling and remediation of some Tibetan traditions (see, for example, Thurston and Lama Jabb). Additionally, with Northeastern Tibetan society facing the sorts of upheavals and dispossessions that some scholars have linked with Han settler colonialism (see Wang and Roche and McGranahan), it is perhaps unsurprising to see Tibetan and other minority cultural producers in China seeking inspiration in tricksters, and sometimes channeling that trickster energy in their own lives. In China, more broadly, many minority cultural producers have found inspiration in oral traditions. Nuosu (Yi) poets from Southern Sichuan, for example, frequently reference their epic heroes, religious traditions, and cosmologies in new poetic creation to tremendous effect (Bender, “Dying Hunters” 125), as has the Wa poet Burao Yiluo (Bender, “Echoes from Si Gang Lih” 108). However, while reference to vernacular and oral tradition is common among minority poets and authors in the PRC, the outright retelling of oral traditions is less common. Tibetan authors and poets, meanwhile, do more than reference oral and vernacular tradition. They retell them in various media. In the 20th and 21st centuries, they inject new life into select Tibetan folk narratives. However, the question remains: will these efforts be enough to sustain these traditions moving forward?

Works Cited

Abrahams, Roger D. “Trickster, The Outrageous Hero.” In Our Living Traditions: An Introduction to American Folklore, edited by Tristram Potter Coffin, Basic Books, pp. 170-179.

Alai 阿來. Chen’ai luo ding / 尘埃落定 (The Dust Settles). 1998. Renmin wenxue chuban she, 2006.

—. Red Poppies: A Novel of Tibet. Translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-Chun Lin. Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

—. “Agu dunba” 阿古顿巴 (Uncle Tonpa). Aba Alai 阿坝阿来 (Alai of Aba). Zhongguo gongren chubanshe, 2004, pp. 88-100.

—. Gesaer wang 格萨尔王. Chongqing chuban she, 2009.

—. Personal interview. 1 May 2010.

Aris, Michael. “‘The Boneless Tongue’: Alternative Voices from Bhutan in the Context of Lamaist Societies.” Past and Present, vol. 115, no. 1, May 1987, pp. 131–164.

Babcock-Abrahams, Barbara. “A Tolerated Margin of Mess: The Trickster and His Tales.” Journal of Folklore Institute, vol. 11, no. 3, Mar. 1975, pp. 147-186.

Ballinger, Franchot. Living Sideways: Tricksters in American Indian Oral Tradition. U of Oklahoma P, 2004.

Bauman, Richard. “The Remediation of Storytelling: Narrative Performance on Early Commercial Sound Recordings.” Telling Stories: Language, Narrative, and Social Life, edited by Deborah Schiffrin, Anna DeFina, and Anastasia Nylund. Georgetown UP, 2010, pp. 23-44.

—. “The ‘Talking Machine Story Teller’: Cal Stewart and the Remediation of Storytelling.” The Individual and Tradition: Folkloristic Perspectives, edited by Ray Cashman, Tom Mould, and Pravina Shukla. Indiana UP, 2011, pp. 71-92.

Bender, Mark. “Dying Hunters, Poison Plants, and Mute Slaves: Nature and Tradition in Contemporary Nuosu Yi Poetry.” Asian Highlands Perspectives, vol. 1, 2009, pp. 117-158.

—. “Echoes from Si Gang Lih: Burao Yilu’s ‘Moon Mountain.’” Asian Highlands Perspectives, vol. 10, 2011, pp. 99-128.

—.“Ogimawkwee Mitiwaki and ‘Axlu yyr kut’: Native Tongues in Literatures of Cultural Transition.” Comparative Literature: East and West, vol. 15, no. 1, 2011, pp. 82-103.

—. “Butterflies and Dragon-Eagles: Processing Epics from Southwest China.” Oral Tradition, vol. 27, no. 1, Mar. 2012, pp. 231-246.

Berry, Chris. “Pema Tseden and the Tibetan road movie: space and identity beyond the ‘minority nationality film.’” Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol. 10, no. 2, 2016, pp. 89-105.

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT P, 2000.

Briggs, Charles L. and Richard Bauman. “Genre, Intertextuality, and Social Power.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, vol. 2, no. 2, Dec. 1992, pp. 131-172.

Carroll, Michael P. “The Trickster as Selfish-Buffoon and Culture Hero.” Ethos, vol. 12, no. 2, Summer 1984, pp. 105-131.

Chen A Xiao 陈a晓. Xueshan, caodi, chuanshuo: shaonian Dengba de gushi 雪山,草地,传说:少年登巴的故事 (Snow Mountains, Grasslands, Legend: The Story of Young Tonpa). www.kuaikanmanhua.com/web/comic/182868/. Accessed 13 June 2022.

Gibbs, Levi S. “‘Forming Partnerships’: Extramarital Songs and the Promotion of China’s 1950s Marriage Law.” The China Quarterly, vol. 233, Mar. 2018, pp. 211-229.

Goldstein, Melvyn C. with Gelek Rimpoche and Lobsang Phuntsog. Essentials of Modern Literary Tibetan: A Reading Course and Reference Grammar. U of California P, 1991.

Grewal, Anup. “Contested Tibetan landscapes in the films of Pema Tseden. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol. 10, no. 2, 2016, pp. 135-149.

Hearne, Joanne. “Indigenous Animation: Educational Programming, Narrative Interventions, and Children’s Cultures.” Global Indigenous Media, edited by Pamela Wilson and Michelle Stewart, Duke UP, 2008, pp. 89-108.

Heimbel, Jörg. “On the Historicity of the Tibetan Folk Tale Hero A khu sTon pa [Version IIa].” 2008. www.akhustonpa.blogspot.dk/2008/03/on-historicity-oftibetan-folk-tale.html. Accessed 17 Aug. 2009

Heimbel, Jörg. “A khu ston pa Bibliography.” 2009. www.akhustonpa.blogspot.com/. Accessed 8 Aug. 2010.

Khedrup, Kelsang, editor. Tibetan Folkstories: Nyichoe Zangpo: Aku-Tonpa in Nedong. Paljor Publications, 2003.

Klapp, Orrin E. “The Clever Hero.” Journal of American Folklore, vol. 67 no. 263, Jan.-Mar. 1954, pp. 21-34.

Klu rgyal rA ti. Personal interview. 11 February 2015.

A khu ston pa ཨ་ཁུ་སྟོན་པ། [Uncle Ston pa]. Directed by Klu rgyal rA ti ཀླུ་རྒྱལ་རཱ་ཏི།, 2014.

Kun mchog dge legs, Dpal ldan bkra shis, and Kevin Stuart. “Tibetan Tricksters.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 58, no. 1, 1999, pp. 5-30.

Lama Jabb. “Currents of the Tibetan National Epic in Contemporary Writing.” The Many Faces of King Gesar, Brill, 2022, pp. 265-296.

Löhrer, Klaus. “The Quest for Aku Dönpa – The Master-trickster from Tibet’s Lhasa Region – IATS-version”

www.academia.edu/37464978/The_Quest_for_Aku_Tonpa_The_Master_trickster_from_Tibets_Lhasa_Region_IATS_version, 2013.

McGranahan, Carole. “Chinese Settler Colonialism: Empire and Life in the Tibetan Borderlands.” Frontier Tibet: Patterns of Change in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands, edited by Stéphane Gros, Amsterdam UP, 2019, pp. 517-540.

Orofino, Giacomella. “The Long Voyage of a Trickster Story from Ancient Greece to Tibet.” Tibetan Literary Genres, Texts, and Text Types: From Genre Classification to Transformation, edited by Jim Rheingans. Brill, 2015, pp. 73-85.

Ra se dkon mchog rgya mtsho ར་སེ་དཀོན་མཆོག་རྒྱ་མཚོ།. 1996. A khu bstan pa’i byung bar thog ma’i bsam gzhigs ཨ་ཁུ་བསྟན་པའི་བྱུང་བར་ཐོག་མའི་བསམ་གཞིགས། [Initial Thoughts on the Origins of Uncle Tonpa]. Gangs ljongs rig gnas གངས་ལྗོངས་རིག་གནས། [Tibetan Culture]. 30: 92-96

Radin, Paul. 1956. The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology. New York: Philosophical Library.

Rinjing Dorje. 1997. Tales of Uncle Tonpa: The Legendary Rascal of Tibet. Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press, Inc.

Squint, Kirsten L. 2012. Gerald Vizenor’s Trickster Hermeneutics. Studies in American Humor 3(25), 107-123.

Sichuan Sheng minjian wenyi yanjiu hui 四川省民间文艺研究会, ed. 1980. A kou deng ba de gu shi 阿叩登巴的故事 [Stories of Uncle Tonpa]. Chengdu: Sichuan Minzu chuban she.

Silvio, Teri. 2007. Remediation and Local Globalizations: How Taiwan’s “Digital Video Knights-Errant Puppetry” Writes the History of the New Media in Chinese. Cultural Anthropology. 22(2): 285-313.

Thurston, Timothy. 2007. Trickster and Outcasts in modern Tibetan Literature: An Examination of Folkloric Character Types in Alai’s Novels. Columbus, OH: MA Thesis.

–. 2019. The Tibetan Gesar Epic beyond Its Bards: An Ecosystem of Genres on the Roof of the World. Journal of American Folklore. 132(524), 115-136.

Tshe dbang rdo rje, Allie Thomas, Kevin Stuart, dPal ldan bKra shis, and ‘Gyur med rgya mtsho. 2006. Tibetan-English Folktales. Unpublished teaching material.

Vizenor, Gerald. 1990. Trickster Discourse. American Indian Quarterly. 14(3):277-87.

Wang, Ju-han Zoe and Gerald Roche. 2021. Urbanizing Minority Minzu in the PRC: Insights from the Literature on Settler Colonialism. Modern China. DOI:10.1177/0097700421995135

Yuan, Haiwang, Awang Kunga and Bo Li. 2015. Tibetan Folktales. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Notes

[1] A previous version of this article was presented as a paper for the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Folklore Society. I am also grateful for a fellowship from the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship, during which the paper was reworked into an article. My thanks go to the three anonymous reviewers of this article for their generous feedback, which greatly improved this article. Any remaining mistakes, infelicities, or omissions are entirely my own.

[2] With the exception of Uncle Tonpa, this article uses the Extended Wylie Transliteration System for Tibetan terms and pinyin for Chinese terms.

[3] For more on Nyi chos bzang po, see, for example, Khedrup 2003.

[4] From personal communications with young Tibetans from across the Northeastern Tibetan region of Amdo, the more ribald of the trickster’s stories are unlikely to be considered appropriate in mixed company.

[5] My thanks to an anonymous peer reviewer for pointing this out.

[6] See Heimbel (2009) for a more complete bibliography.

[7] Interestingly, the search returns no results with audio or video recordings of people telling stories about the trickster’s exploits.

[8] The introduction makes no mention about the delay in publishing, but the back pages suggest that the 1980 printing of the collection was its first printing. It is possible that publication was postponed during the turmoils of the Maoist period. A Tibetan version exists, but the author did not have access to it at the time of writing.

[9] With examples from Nuosu (Yi) and Miao epic traditions, Bender (Dying Hunters, 125) demonstrates that this is a common approach employed by collectors and folklorists in China.

[10] Gibbs (226) shows how Chinese folklore collectors in the Maoist period frequently excluded, minimized, and rationalized bawdy content in the collection of oral traditions.

Dr. Timothy Thurston is Associate Professor in the Study of Contemporary China at the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds. He is currently an UKRI Future Leaders Fellow researching language, folklore, and society in Northwest China. He holds both M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in East Asian Languages and Literatures from The Ohio State University. Prior to joining the University of Leeds, he completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Dr. Thurston has authored many academic papers and book chapters and he is now working on a book monograph tentatively entitled Satirical Tibet: Voice, Media, and Ideology in a Modernizing Amdo Comedy and the Making of Modern Tibetan(s). In addition to teaching and research, Dr. Thurston is Yeshe’s performance editor and the co-host of the podcasts New Books in Folklore and New Books in East Asian Studies.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities