ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Photographs from Tibet: Charles Bell or Rabden Lepcha?

Kunsang Kyirong

Abstract: In this explorative photo essay, the author focuses on an archival research trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum. Based on the research visit and some preliminary investigation, the author shares her insights into the photographic collection of Sir Charles Bell.

Keywords: Photography, Archives, Museums.

Fig 1: The author in the researcher’s area, the Pitt Rivers Museum, 2022.

I was introduced to the Charles Bell archival collection during a day trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum. As we enter the museum, we were immersed in a dense space packed with numerous glass display cases containing the archaeological and anthropological collections of the University of Oxford. We quickly made our way through the main floor, passing cases of ivory, bones, masks, trinkets, rope baskets, a taxidermied fox, and other items of mysterious provenance. Finally, we entered the researcher’s area and I put on a pair of white cotton gloves to view the materials I had previously requested to access. The assistant curator noted that this collection, besides a few other boxes, had been set aside to be thrown out by a college many years ago. Luckily someone went through these boxes only to realise that inside them existed some of the earliest photographs taken in Tibet, and that’s how they ended up in the collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum.

Charles Bell (October 31, 1870 – March 8, 1945) was a British diplomat who served as the Political Officer for Sikkim, Bhutan, and Tibet (1908 – 1918) and remains one of the most significant figures in Anglo-Tibetan history. As a scholar of Tibet, he amassed and left behind an extensive collection consisting of diaries, notes, and photographs. At the Pitt Rivers, I was given access to a selection from his photography collection, accompanied by a corresponding handwritten list. The photographs showed the range of societal access Charles Bell was privy to—portraits of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, aristocratic families, lay families, imprisoned people, and beggars with their tongues sticking out. Among these photos were some mundane and candid images of groups of people standing in laneways, often laughing and with messy hair; fruits being sold in the market; household items; and the gifts Bell received in Tibet. The man’s curiosity behind the camera is as remarkable as the societal range Bell could access and capture. In his book The People of Tibet, Bell meticulously describes his observations of the Tibetan people and their culture. He gives context to the photographs in his writings, which also amply illustrate his command of the Tibetan language along with his sensitivity towards Tibetan culture. He forwards critiques of other Europeans and, occasionally, the Japanese for stereotyping Tibetans as lazy. Instead, he writes about how the Tibetans are hardworking. How when the work is done, and there is nothing left to do, there is a sense of contentment. He writes, “They can stay doing nothing for a long time without falling into boredom or peevishness” (Bell 1928: 40). Bell’s observations still pertain to a point of view, how he chooses to portray those differences between self and other, whether the same as us with merely superficial differences or different from us with opaque differences, can be interpreted to the analysis he confronts.

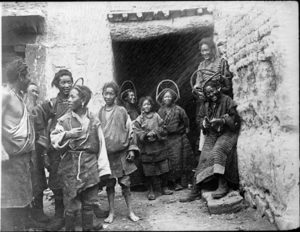

Fig 2: Sir Charles Bell or Rabden? Ten servants at Badu La’s house, near Shigatse 1904-1920. [Image Credit – Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Accession Number: 1998.286.85]

Fig 2 is a photograph of a group of children and adults. The working-class girls wear the Tsang headdress, which branches out, creating a semi-circle over the crown of the head. Bell noted that they were the household servants of a Tashi Lhunpo official. Many of them are caught with their mouths breaking into smiles, awkward, and avoidant of the camera. Three of them look towards the camera. The boy standing near the center sticks out, his expression is maybe perplexed, and he is the only one without shoes.

Fig 3: Sir Charles Bell, Rabden Lepcha, Gangtok, 1903-1921.

[Image Credit – Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Accession Number: 1998.286.6.1]

Bell’s activity is addressed in Photography in Tibet, authored by scholar and curator for Asian Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Prof Clare Harris. As the first historical survey of photography in Tibet and the Himalayas, the book details the historical relationship of photography in Tibet and how photographs “have played a role in defending, inscribing and imagining a place called Tibet” (Harris 2016: 13). Harris notes how the relationship of photography was never one of only orientalism. She introduces another relationship with Tibet and her early photographers, where the production and consumption of images were also made by Tibetans.

Fig 3, Bell’s working Sikkimese orderly, Rabden Lepcha, is captured in a portrait looking straight ahead. Lepcha was instrumental to many of Bell’s photographic achievements, and their relationship is one which was shared behind the camera. In Sikkim, the Lepchas are known as one of the country’s earliest inhabitants; their language is connected distantly to Tibetan. In The People of Tibet, Bell describes how Lepchas learned quickly and how Rabden Lepcha took Bell’s photographic work more into his own hands with each passing day. Most photographs in the collection are now attributed to “Charles Bell or Rabden Lepcha?” because there is no clear documentation of who took which photo.

Fig 4: Sir Charles Bell or Rabden? Kitchen utensils such as cooking pots, teapots, tea urns and water buckets in a house in Chumbi Valley, 1903-1921. [Image Credit – Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Accession Number: 1998.286.93.1]

Fig 4 has an arrangement of objects—saucepans, a tea kettle, a steamer, a tea churner, utensils, and a water bucket rest undisturbed. This image of a kitchen filled with household cooking supplies, shot from a low angle, has light illuminating the foreground. The question of where the camera is harnessed in space comes to mind when contemplating which photographer may have captured this still life. Since Bell was significantly taller than Lepcha, the heavy build of the wet plate camera would have possibly made it difficult to adjust and assist Lepcha’s point of view. Rabden being a novice to photography, one might assume that the photographs slightly off-center or out of focus were taken by him. The more I tried to decipher who took which photo, an increasing sense of futility surfaced.

The written accounts by Bell offer a context beyond the image and an insight into his subjective point of view. The ethnographer often starts from the point of difference; in one section, Bell writes about his lodging in various homes and time spent in a series of farmhouses. He describes one room as being above the sheep-yard with four to five hundred sheep. There had been heavy rain, and the air was warm, creating a large amount of black slime, which he describes as “like living on a manure heap” (Bell 1928: 52). Yet, from the roof, he watched the Tibetan children dance, whirling round and round, and in earshot were noticeable joyous conversations between an old man and some women from the household. Bell’s observations are sharp, as are the differences in experience. He notices that while an unpleasant smell rises from underneath his room, those around him go on smiling and are seemingly undisturbed.

Fig 5: Rabden Lepcha, Dorje Pamo on her throne at Samding Monastery, November 1920. [Image Credit – Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. Accession Number: 1998.285.137.1]

Bell has a chapter dedicated to the women of Tibetan society in his book The People of Tibet. He mentions how the status of women was relatively equal to that of men. A few differences pertain, but generally, any traveller would feel that “few things impress him more vigorously or more deeply than the position of Tibetan women” (Bell 1928: 147). He writes how they are at ease with men and how their equality of rights surpassed those of Western women at the time. This also pertains to religious life, where Bell described meeting Dorje Pamo – ‘The Thunderbolt Sow’ – the third highest ranking figure in the Gelug hierarchy after the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama. He described meeting the twenty-four-year-old religious figure at Samding Monastery, where she sat on the same throne that she used as her bed to sleep, residing in a monastery of only monks, and was intuitively able to tell the time of sunrise and sunset. Bell had made one previous failed attempt to photograph Dorje Palmo. However, Rabden Lepcha was later granted access by the Thunderbolt Sow herself.

In Fig 5, the photograph is dark and lacks exposure, but she can be seen from her seat staring onward, her face slightly sombre. What difference would have made if Bell took the photograph? And why might Dorje Palmo have requested Lepcha? Bell wrote how Palmo had commented on his language skills, being pleasantly surprised at his ability to speak to her in Tibetan. She is quoted as saying, “To talk to one who cannot understand and reply easily is like one simpleton babbling to another” (Bell 1928: 168). Yet, the ability to communicate was not enough to allow Bell to photograph her himself.

Bell’s book The People of Tibet offers the insights of a skilled ethnographer. He counts the details, the stacks of hay, and the types of crops and foliage, besides his sense of perspective, which carries forward the narrative in his book. There is often a retelling of stories, a set of observations, and a cheerfulness which is gleaned from an inward difference of perspective, tolerant to the circumstances. Lepcha’s observations and presence juxtapose an additional interiority. This is not articulated by Lepcha on paper but is suggested through some of the decisions made behind the camera and the subjects who request his point of view.

Before leaving the Pitt Rivers, the assistant curator asked me if I would like any images enlarged and printed for my travels. I chose one of Rabden Lepcha. Not much is known about Lepcha and if he continued to use his skills in photography throughout his life. Many of the photographs he and Bell captured are available to view on the Pitt Rivers website in their digital Tibet Collection. Their work exists amongst many other photographic works taken by various colonists and ethnographers and is available to browse.

Works Cited

Harris, Clare. 2016. Photography and Tibet. London: Reaktion Books.

Bell, Charles. 1928. The People of Tibet: London: Oxford University Press.

Kunsang Kyirong is a filmmaker and animator working in Toronto. Her practice explores themes of memory and immigration, often through a hybrid method that integrates documentary elements within fictionalised narratives. Her work has been screened at festivals such as the Festival du Nouveau Cinéma, Vancouver International Film Festival, Ottawa International Animation Festival, and Dharamshala International Film Festival. She is currently working on her first feature film, ‘100 Sunset’.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities