ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

“Now We Can Tell Tibetan Stories”: Portrait of the Filmmaker as an Old Friend

Françoise Robin

Abstract: Pema Tseden managed to make a certain ‘Tibetan dream’ come true: creating almost from scratch and fostering a Tibetan cinema without compromise under the vigilant and suspicious eye of the Chinese state. He proved that Tibetan cinema by Tibetans was not only possible, countering the usual narrative of backwardness attached by the state to Tibetans in the PRC, but also that it could be celebrated internationally. This essay is an overview of the author’s almost two decades of friendship and work with Pema Tseden on his films. It testifies to Pema’s constant engagement and commitment to making a Tibetan film scene emerge and discloses a few lesser-known aspects of his life and career. It is abundantly illustrated with photographs.

Keywords: Pema Tseden, Tibetan cinema, minor cinema, Venice Film Festival

Pema Tseden dedicated the second half of his brief life to materialize Tibetan cinema, and he also set high-quality standards for Tibetans and other filmmakers in the PRC (see Duzan in this issue of Yeshe). It is my privilege to have a mutual friendship and professional collaboration with him for over twenty years. Personal memories can be as boring as an endless slide, watching the evening upon a friend’s return from a trip. Verging on the anecdote is always a risk. With that possible pitfall in mind, I have focused here on glimpses, snapshots, and snippets, through which readers will, or so it is hoped, get a better idea of the Tibetan cinema scene that Pema strived to establish from nascency, and also know him better as a person.

Pema Tseden and I met first in Xining in 2002 when I was in the third year of my Ph.D. in contemporary Tibetan literature. I found his writings intriguing and interesting, somehow different, setting him apart from other writers. They were more contained, more subtle, more enigmatic. A short story in particular, “Let’s go to Tsethang” (Tib. Rtse thang la ’gro, published in the early 2000s), had struck me: a group of young Amdowas, traveling to Lhasa and Tsethang (the cradle of Tibetan empire), came across young Han Chinese Tibet-enthusiasts.[1] Reflecting upon this short story, its content seems to indicate Pema’s early interest for introducing Tibetan culture from a Tibetan perspective to an open-minded Han Chinese intellectual and artistic audience. We thus met through a mutual friend of his—the tightknit intellectual scene in Amdo, as in most places in Tibet, makes contacts very easy. Pema Tseden, a quiet, peaceful, and thoughtful young man, struck me then as someone more eager to share his hopes and dreams about Tibetan cinema than his literary career. He even mentioned that he was aiming at the Cannes Film Festival someday. Not knowing that he had already engaged into cinema, I was taken aback and, I must confess, thought he was totally unrealistic. I should have known better: he was a man of few but carefully weighed words. Since that first encounter, we met regularly. In 2005, an international delegation of PRC filmmakers visited France for the celebration of the hundred years of Chinese cinema. He was of course the only Tibetan member. After his first feature film The Silent Holy Stones was shown, a French woman commented to him: “This is not real Tibet!” He smiled recalling that moment, which comforted him in his mission. As he often declared, people had been nurtured by Western-centred and Sino-centred (mis)representations of Tibet on screen and his mission was to rectify that. Moreover, his native place Amdo was still marginal at that time. Most outsiders interested in Tibetan matters had been little exposed back then to Amdo or Kham: Tibet was Lhasa or Central Tibet. So, although that French watcher’s remark was preposterous, it did touch upon a serious question for Pema: given Tibet’s vastness and variety of regional customs and languages, what type of “Tibet” was he to represent?

One year later, in July 2006, he organised a public, open-air screening of that same film, next to Kou monastery (Tib. Ko’u dgon), in Chentsa (Tib. Gcan tsha, Malho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai). Silent Holy Stones had been shot there, a choice partly due to Gangzhun (Tib. Gangs zhun, aka Sangye Gyatso, Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho, who contributes to this issue). Gangzhun, his university friend turned producer-in-the-making, was native from that area, knew the lama at the monastery, and had facilitated contacts between Pema and the monastery. We shared a car to reach the location and had time to discuss leisurely the difficulty of being a Tibetan filmmaker in the PRC. At that time, he was just embarking upon that new path, which he knew well was fraught with difficulties. He had to first build a Tibet-centred visual identity, which meant contesting what had prevailed until then, i.e., both Western preconceptions and a thoroughly Sino-centred filmic representation of Tibet.[2] Also, he was aware of having to tread a very fine line as a freelance Tibetan filmmaker: he was particularly watched by the authorities while also being celebrated by them. He somehow always managed to satisfy both sides through his films: the Tibetan side by making world-quality, Tibet-centred films that indicated, often between the lines, the quandaries of being a Tibetan in the PRC; and the official Chinese side, who could claim that Tibetan culture was flourishing inside the PRC, taking his films as a proof of vitality and thus contradicting gloomy descriptions of Tibet under China as a hell on earth, a description that came from exile Tibetan circles or Western pro-Tibetan ones. Pema as far as I remember was already teeming with projects and had many more films in mind.

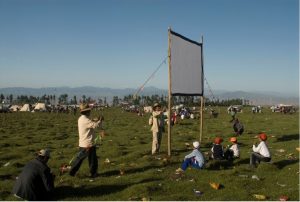

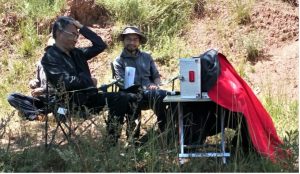

The Silent Holy Stones being a 35mm film, we needed to climb up winding mountain paths leading to the screening area. The staff, hands full of movie reels, screening equipment, and projector borrowed from nearby Rebkong film theatre, reached a vast plain. They set up a large piece of cotton, hung between wooden poles, which served as a makeshift screen. Before dusk, more and more people gathered, seating on the grass. An ornate Tibetan tent was also erected, to receive and entertain important guests.

Preparation for the open-air screening of Silent Holy Stones, Chentsa, Summer 2006 ©Gilles Sabrié

Preparation for the open-air screening of Silent Holy Stones, Chentsa, Summer 2006 ©Gilles Sabrié

The evening was bright, warm, and clear; the atmosphere jolly and festive. The screening provided a welcome and unusual source of entertainment at a time when mobile phones, videos, films, and TV series were still a rarity in rural areas. Hundreds of people, often whole families, saw for the first time a film about their own life, in their own language on a screen. For Pema, it was a way of celebrating with that local community the feat of having succeeded in making his film. But, on a larger scale, he was giving them what he felt was long overdue: a filmic representation of their culture, from the inside, and to which they could easily relate.[3] Some in the audience were thrilled to be represented in a rather faithful way on screen, while others could not see the point of seeing their own, uneventful life, portrayed in a film—an involuntary indication that Pema’s goal had been fulfilled, that of being as close as possible to a certain Tibetan reality. He held to that mission until the end, declaring in 2021: “I hope our films could be authentic enough for Tibetan people to recognize their own everyday lives when they see it. Previous films shot in Tibet may tell stories in a Han Chinese way of thinking.” [4]

An enthralled audience watching Silent Holy Stones, Chentsa, Summer 2006 ©Gilles Sabrié

In 2008, Pema came over to France for the second time. He was hopeful that his second movie The Search would be shortlisted at the Cannes Film Festival. Xu Feng, a partly French-based Chinese professor of cinema (see his essay in the present issue), introduced him to the late Pierre Rissient, a producer and discoverer of Asian independent cinema in France.[5] Pierre Rissient was very enthusiastic about The Search but strongly suggested that Pema cuts thirty minutes off the film, which was almost three hours long. Pema complied reluctantly—it was like “cutting the hands of one’s child” he said. Despite this sacrifice, and much to his dismay, The Search failed to be selected by the Cannes. I was witness to the phone call that a furious Rissient made to the person in charge of the final selection in the Cannes Festival: he basically told him they were idiots. Pema looked quiet, but his hopes were certainly shattered inside.

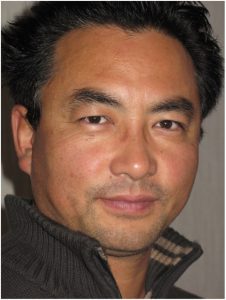

Pema Tseden, 2008 ©Françoise Robin

In the summer of 2009, we had tea with his friend and director of photography Sonthar Gyal on the roof terrace of a Tibetan teahouse overlooking the Jokhang Square in Tibet’s capital, Lhasa. Both Pema and Sonthar Gyal were taking part in a documentary film about Samye Monastery (Tib. Bsam yas dgon pa) – Sonthar Gyal told me later that Pema had trouble with the altitude already in Samye. We discussed at length their film tastes, and I remember thinking it was wonderful to spend time in the historic heart of Lhasa, discussing Ingmar Bergman’s movies with such a distinguished and knowledgeable company, with a view to the Jokhang.

In 2011, we met again in New York, this time for the Third International Conference on the Tibetan Language, hosted and organised by the Latse Library. One afternoon, along with Dukar Tserang, the sound engineer who worked with him at the beginning before embarking upon his own film career, we prepared for the evening’s talk, which both of them had been invited to give.[6] That was necessary due to my limited command on Amdo dialect. For a reason I cannot remember, during the talk at Latse, I deviated from what we had agreed upon and dragged him towards unplanned questions. He was upset. But I now understand his reaction: he was still struggling to fulfil his difficult mission—establishing a Tibetan cinema—and he needed to master most aspects of that mission. That evening, someone asked him why his movies were slow, lacked spectacularity, and may not be that attractive to more popular audiences. He explained that Tibet was a rural area, sparsely populated, and lacked cinema halls. He explained that no producers would engage funds in comedies that appealed only to the Tibetan taste. Instead, he had to develop scripts that could appeal to the Chinese as well as international audiences while being true to Tibet.

In early July 2012, thanks again to Xu Feng’s efforts and good connections in the French film scene, Pema was invited to the La Rochelle Film Festival (FEMA), a well-established festival, that offers a combination of promising directors and repertoire films. Every year, a section is dedicated to the cinematography of a ‘minor’ or less-known national cinema. Tibet not being a country, the section was framed as an introduction to Pema’s filmography. He had just finished Old Dog, which he showed to a packed theatre, and he also showed his early films.

Catalogue of the La Rochelle Film Festival (FEMA), 2012

The few days in La Rochelle were spent in meetings and conversations with the public, and several interviews, during one of which he declared: “I do not think cinema can save a culture, but it can contribute to its memory.”[7] It is also in La Rochelle that he shared an interesting story about his childhood. He has already recalled that early period in “Three Photographs from my Youth,” published in Yeshe:

[M]y paternal grandfather […] was convinced that I was the reincarnation of his uncle. His uncle was a Tibetan Buddhist monk of the Nyingma school who owned many volumes of sutras and was rather well educated. My grandfather said that it was thanks to his uncle that he could recite some Buddhist scriptures and understood some Nyingma rituals, and he was grateful for this. Supposedly, when I was very young, I spoke about some things that had to do with his uncle, and that was why my grandfather was so sure that I was the reincarnation of his uncle.[8]

What Pema did not write in this piece, originally published in China, but which he confided to me in La Rochelle, is that his grandfather had another ‘proof’ that unmistakenly confirmed Pema as the reincarnation of his own uncle. Surprisingly for a boy from a monolingual, rural background, Pema excelled in the Chinese language. The grandfather found an explicatory Buddhist logical frame: just as his uncle had learnt smattering of Chinese because he had spent years – and died – in a Chinese labour camp,[9] so could Pema express himself at ease in the Chinese language on account of a karmic residue (Tib. bag chags) from his previous life. The great Amdo Uprising in 1958 was, and still is almost seven decades on, a topic that cannot be discussed openly in the PRC despite the immense trauma it left on a whole generation. During the festival, another instance of partial disclosure of reality occurred. One memorable evening, we had dinner with Michel Piccoli (1925-2020). Piccoli had adored Old Dog and asked technicalities about the particularly gripping and tragic last scene: how had he filmed it? With what camera? Piccoli’s enthusiasm was quite a compliment, coming from a famous French actor who had played under such illustrious directors as J.-L. Godard, F. Truffaut, and L. Bunuel to name just a few. Pema, after answering Piccoli’s question, revealed that the censorship authorities had not approved the tragic ending. Despair was not allowed. But Pema had found a smart way to circumvent that order and satisfy the authorities as well as his own artistic imperatives. A few years later, Pema confided the complexity of finding topics that were both meaningful for him and that accorded with the imperatives of the censorship bureaus, as they would always scrutinise every film project in the PRC, especially when emanating from ‘minorities’ with a reputation of being unruly. He said:

Tibet is filled with brilliant stories. In the beginning, you don’t know whether it’s a historical film, a fairy tale, a realistic story because Tibet is just full of excellent stories. It’s a real reservoir. But not everything is allowed. When you are involved in cinema, you realise that little by little. At first, you think, “there, that’s no problem”. You can pick your script like that. It’s easy. But then problems arise.[10]

Pema Tseden in La Rochelle, July 2012 ©Pascal Couillaud

Our paths kept crossing, in yet another place. In August 2014, he presented his film Sacred Arrow, at the Beijing Sports Film Festival. Pema always harboured mixed feelings about his fourth feature film, although it was a favourite among many Tibetans. It had been commissioned by authorities in Chentsa, where he had shot Silent Holy Stones. They hoped to boost tourism by introducing highlights of the area to a wide public: stunning scenery, archery competition, as well as Dorje Drak Monastery (Tib: Rdo rje brag),[11] reputed as a site that holds the bow having pertained to the regicide Lhalung Pelgyi Dorje (Tib. Lha lung dpal gyi rdo rje, 9th c.).[12] This time, compromise was not demanded by the whims of censorship but was necessary to fulfil the sponsors’ hopes for a popular movie. They did not intervene in the script.

Until Balloon (2019), and even for Snow Leopard (2024), finding enough capital to make films was a challenge for Pema. Having a sponsor for Sacred Arrow was a welcome respite. This movie stands aside in his filmography for lacking his high aesthetic standard and above all the open ending that characterises his otherwise more complex films. In fact, he seldom mentioned this film in his cinematography. But it deserves attention for two reasons: it is often mentioned as a favourite among Tibetan audiences (it can be considered a ‘popular movie’), and it was the first film in which Pema succeeded in bringing together actors from Amdo, Kham and Utsang, the three traditional regions of Tibet. This was his way of pushing the limits and encompassing all areas of Tibet in his filmography: being an Amdo Tibetan director filming in Amdo with Amdo characters was fine, but being able to bring Tibetans from all regions, despite dialectal and logistical obstacles, was another dream of his, which he fulfilled. Sacred Arrow’s screening in Beijing was a success: Beijing-based Tibetan intellectuals such as the Gesar epic specialist Jampel Gyatso (Tib. ’Jam dpal rgya mtsho) or the writer Rangdra (Tib. Rang sgra), as well Sonthar Gyal were among the audience, and shared their feelings in the Q&A session that followed. A Han Chinese lady, marvelling at Pema Tseden’s talent as a filmmaker (his fame was still limited then) and at the richness of Tibetan traditions that he had managed to convey in his film, compared favourably Pema’s film with Uyghur films. In the evening, with a handful of friends, we had dinner at Makye Ama, a hype Tibetan restaurant in Beijing. Pema’s son Jigme Trinley (b. 1997) joined us. It was my first encounter with Pema’s only child, who was soon to follow in his father’s steps. Jigme had been brought up in Beijing: his mother, Yudrontso, worked as a medical practitioner, and his father was busy establishing his cinematographic career in the capital city. Jigme had thus been educated in a Chinese-language schools, while speaking Tibetan at home. Back then and still now, Beijing offers no provision even for a bilingual Tibetan-Chinese education.[13] Tibetans living in Beijing, sometimes highly educated in the Tibetan language and learned in Tibetan civilisation, as they work for research institutes or publishing houses, are left finding solutions to enable their children access to some tuition in Tibetan (private courses, holidays back in the “phayul”, i.e. at the grandparents’, etc.). This is why Pema and Yudrontso sent Jigme in 2013 for one year to the “Jigmed Gyaltsan Welfare School,” a famous Tibetan private vocational high school in Amdo located in Golok (Tib. Mgo log), whose success lies in “combining the traditional and the modern in the education systems in Tibet. This approach effectively incorporates the essence of Tibetan traditional culture and has absorbed the essentials of the modern science curriculum.”[14] They may have been among the first Chinese-city-dwelling Tibetan intellectuals who had taken up that step—and may have set a trend, as more and more Tibetan parents, worried by the lack of anchoring in Tibetan culture of their children brought in a pure Chinese and Sinophone education system, made a similar decision in later years. Skipping out of the Chinese curriculum system was not devoid of consequences for Jigme since he would have to double one class when back in Beijing. That type of calculation is brave in the context of the hyper competitive Chinese school system and is a good indication of the priorities of Jigme’s parents: sacrificing one year in the highly competitive education system to ensure their son’s rootedness in his ancestral culture and language, rather than uprooted social mobility. Young Jigme was thus back from Golok, with a vastly improved Tibetan fluency, after almost one year of full immersion into a nomadic, remote, Tibetophone environment over two thousand kilometers away from Beijing. He was interviewed that afternoon by the Tibetan-language channel of Qinghai Radio on the topic of his experience. His father was proud. Since then, Jigme has maintained his level of spoken Tibetan. Pema’s wish was for him to receive higher education for one year in Tibetan literature at Lanzhou Northwest Nationalities Institute. Unfortunately, the Tibetan language was scrapped recently from that top university which had nurtured so many intellectuals we know today, including Pema Tseden.[15] Jigme could still register at the National Minzu Institute in Beijing, but Tibetan taught and spoken there is mainly Lhasa or “common” Tibetan, which Jigme does not master.

Sonthar Gyal (left) and Pema Tseden (right), Makye Ama Tibetan Restaurant, Beijing, August 2014 ©Françoise Robin

It is now a commonly established fact that 2015 was a turning point in Pema Tseden’s career: Tharlo was shown in the Venice film festival [as all his subsequent films: Jinpa (2018), Balloon (2019), and (Snow Leopard) 2023]. His initial vision, that of forging a quality Tibetan film scene, had paid off: his films had gained international visibility and recognition.

Yangshik Tso and Pema Tseden in Venice for the world premiere of Tharlo ©Anne-Sophie Lehec

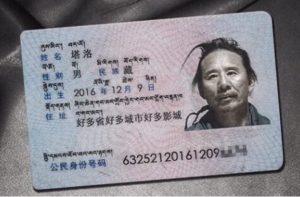

He was widely acclaimed among Tibetans as the first Tibetan ever to be shortlisted at the prestigious film festival. It is hard to imagine the pride felt by a community downtrodden in the PRC as backward and in need of patronising support and development.[16] The aesthetic, radical aesthetic choice that characterised Tharlo (austere black and white, slow takes, limited dialogues with recitations of Mao Zedong’s speech at the beginning and the end), may have puzzled some Tibetan audience but pleased the international audience.[17] Briefly, Tharlo tells of a simple sheep herder, brought up in revolutionary times, with a pure heart, who is required like all citizens of the PRC to have his ID made. Although he fails to see the point of obtaining such a document, he goes to town to start the procedure. There, he meets a hairdresser. Without spoiling the plot, suffice to say that Tharlo faces problems with having his ID; it never materialises. But someone anonymously circulated the ID (see figure below) on social media, with the date of birth corresponding to the date of the release of the film.

Name: Tharlo

Gender: Male

Ethnicity: Tibetan

Date of birth: 2016/12/9

Residence: Many provinces, many towns, many cinemas

(source: WeChat)

Pema Tseden had gone a long way from his beginning, naturalistic, quasi-ethnographic years, and his artistic vision had come to full bloom. In 2017, I interviewed Pema on the reception of Tharlo among Tibetans and Chinese:

At the end of 2016, Tharlo was shown in China, Xining, and Tibetan towns such as Labrang, where there was a cinema. I travelled to accompany the screenings. After a week, the film was distributed in Chinese cinemas in Beijing and Shanghai. It benefitted from a real distribution in many cinemas in China. This is perhaps the first time that a film in Tibetan has been distributed for real, commercially, in China. The film has therefore given rise to a fair number of critical reviews. There have been several interpretations: Chinese film buffs and film specialists have generally been very appreciative, understanding that the film is not just about Tibet or Tibetans. Some Chinese said that they too, in the countryside, were familiar with the phenomenon depicted in Tharlo: “It’s happened to us too, or it’s happening to us. This situation exists now. We have similar situations”, they said. Among Tibetans, several opinions circulated: some said that the film did a good job of showing the changes in the lives of Tibetans, or that it did a good job of representing Tibetans. Then others said that the film was not good, that it was not right to show Tibetans in this light. Some Tibetans said that the film was a love film, others that it showed loneliness. Still others said it showed the human condition. Reactions were very diverse, particularly among Tibetans. Whatever the case, the film remained on screen in Xining for 1 month. [Tibetan] people came from all over the place where we hadn’t been able to show the film, from small villages, monasteries, etc., which didn’t have cinemas. Some didn’t even know how to buy cinema tickets (laughs). And everyone understood the film in their own way… In Chinese cinemas, the film sold one million tickets. That’s not much in China, but it’s a lot for a Tibetan film. Tharlo was selected by around thirty international festivals. But I was not able to attend all of them. It won fifteen to twenty awards. At the Taipei Golden Horse Festival in Taiwan, it won several awards (screenplay, direction, photography, etc.). This certainly enabled the film to be released on Chinese screens. It went to Venice and even though it didn’t win any prizes there, that also helped to get the film released on Chinese screens. It was shown in arthouse cinemas in China, but not in the commercial cinema networks. Finally, several cafés in Tibet are now called “Café Tharlo”.”

That same year, Lhapal Gyal (Tib. Lha dpal rgyal), Pema’s ‘spiritual son’ in cinema, was shooting his debut feature film Wangdrak’s Rain Boots with Pema as the executive producer. With Chime-la (Professor Hoshi Izumi), a seasoned translator of contemporary Tibetan literature from Tokyo University, we asked Pema if we could join the team, to which he agreed.

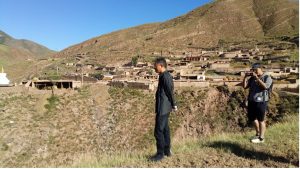

Pema Tseden in Chumar (Tib. Chu dmar), his son Jigme behind him, August 2017 ©Françoise Robin

A driver fetched us in Xining and took us to the school which had been turned into the headquarters of the film in Chumar (Tib. Chu dmar, Hualong District, Qinghai). Two bunk beds had been arranged for us in the women’s dorm.

The dorm for women and children staff hired for Wangdrak’s Rain Boots, August 2017 ©Françoise Robin

The classroom turned into women’s dorm, make up and costumes room, August 2017 ©Françoise Robin

Pema Tseden and Lhapal Gyal during Wangdrak’s Rain Boots shooting, August 2017 ©Françoise Robin

In the few days spent there, we realised how Pema’s presence mattered: he would give advice, make suggestions, offer solutions. Lhapal Gyal told me that with Pema around, actors and staff were more focused and obedient.

Morning session: Pema Tseden gives instructions to the film staff in the courtyard of the school rented as a base, to host the film crew, August 2017 ©Françoise Robin

Pema sharing thoughts and giving instructions to his crew, in a family courtyard used for one of the scenes, August 2017 ©Françoise Robin

It was during a car trip at that time that Pema confided to me how much he still resented not having been selected for the Cannes Film Festival back in 2008. If only festival organisers in the world could understand that being able to set a Tibetan cinema was almost miraculous, that behind the level of professionalism on the screen was a constant bricolage and manoeuvring between money, technology, and politics, maybe they would have considered Pema’s films a little differently. After a few days, Chime-la and I returned to Xining. Pema had arranged for a car to drive us back, and to our surprise had even booked a hotel and a meal at a vegetarian restaurant in Xining. That was one of his other many qualities: he was always considerate to others.

Pema Tseden would usually choose winter to shoot his films since, as he told me once, colours on the Tibetan plateau were so bright in the summer that film watchers, engrossed with the spectacular sceneries, may be distracted from the plot or characters. But in 2018, when I reached Xining again, Pema was about to shoot his next film and he agreed to my request to spend a few days on location. He sent Akang, his cousin-cum-driver-cum-facilitator, to fetch me at the bus station in Thrika (Ch. Guide). From there, Akang went to buy medicine for Pema, who was already suffering from diabetes, and then took us to Pema Tseden’s home village in Dzona (Tib. Mdzo sna), not far from the Yellow River. The shooting of Balloon was to start within a few days, so I was first taken to Pema’s headquarters, a small official and disused compound that he had acquired. Ever since Jigme, now a young adult, had enrolled at the Beijing Film Academy and required less parental supervision, Pema and his wife Yudrontso had returned to Xining, true to Pema’s initial commitment to establish a cinema environment in Tibetan areas.[18]

Courtyard of Pema’s headquarters in Dzona ©Flora Lichaa

The small compound had dorms for the team, along with a common kitchen in which Pema’s aunt operated as a cook with a smiling authority.

Pema’s aunt preparing lunch, August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

Meals were served in the courtyard on long tables. Pema’s office and bedroom were on the second floor.

Front view of Pema’s headquarters in Dzona, July 2018 ©Flora Lichaa

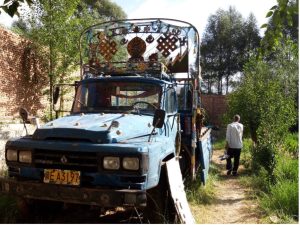

This apparently banal place was in fact full of surprise. During my first lunch there, I heard “O Sole Mio” played at full blast. It was rather unusual to hear this music in Tibet – rather, one hears popular Tibetan songs most of the time. I soon learned that it was the main song of Jinpa (in Jinpa, the song is heard both in Neapolitan and Tibetan, as Pema commissioned a translation of the lyrics; it is interpreted by one of the only Tibetan tenors with an international career, named Dorje Tsering[19]). The team was in a jolly mood, celebrating the recently received news that the film had been shortlisted in the Orizzonti program at the 75th Venice Film Festival (he was to receive a prize for the best screenplay). The truck used in Jinpa’s shooting was also there, in the front courtyard.

Jinpa’s truck, July 2018 ©Flora Liccha

I was also surprized by the opportunity to meet Takbum Gyal (Tib. Stag ’bum rgyal) in these headquarters. He is a celebrated writer whom Pema Tseden had translated into Chinese (see P. Schiaffini-Vedani’s article in this issue). Takbum Gyal was revising the script with Pema.

Takbumgyal (left), Pema Tseten (center, seated), Rabten (center, standing), Kunde (right), Dzona, August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

Jinpa, Pema’s iconic actor, was also present, rehearsing his part along with Sonam Wangmo (Tib. Bsod nams dbang mo), who had played the part of the flirtatious tavern owner in Jinpa. In idle moments, he played the flute or joked with the crew, lending a hand when needed. Sonam Wangmo, an elegant actress and dancer from Lhasa, was now to perform the part of an Amdo peasant. She did not master Amdo Tibetan. Pema had appointed two Amdo language trainers, who were from the area where the plot of the film was to take place.

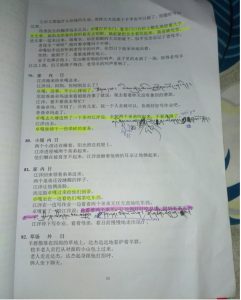

Sonam Wangmo (right) transcribing her lines from the Chinese script into Amdo Tibetan with the help of actor Jinpa (left), and language instructor and staff Loden (middle), August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

Original script of Balloon in Chinese language annotated in Tibetan by Sonam Wangmo, August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

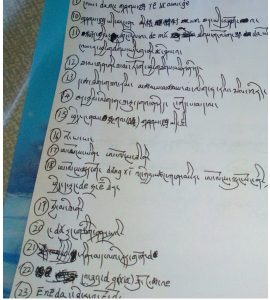

Transcription by Sonam Wangmo of her lines for Balloon, August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

The biggest surprise was yet to come. Loden, one of two language instructors of Sonam Wangmo, himself a budding young filmmaker (see Brigitte Duzan’s article in this issue), asked me if I wanted to go with him to fetch some meat from a freezer located in one the rooms of the compounds. He opened the door, and we entered… the photo studio of Tharlo.

Loden in Dzona showing the props of the photo studio in Tharlo, August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

Then Loden led me with a smile to another room on the ground floor, next to Jinpa’s truck: we entered the hairdresser salon, which plays such a big part in Tharlo.

Writer Takbum Gyal showing props from the salon used in Tharlo , August 2018 ©Françoise Robin

A still of the hairdresser salon from Tharlo

Next to Pema’s private quarters, on the second floor, was the “police station” of Tharlo. Big Chinese letters “Serving the people” could still be read on the wall. There was now a ping-pong table in the middle of the room. I realized that most of the interior scenes from Tharlo were created from scratch in this small compound, Pema’s makeshift cinema studio.

The recreated police station, in Pema Tseden’s headquarters, Dzona

After a few days of rehearsals and preparations, the team moved 200 kilometres north to the shores of the Kokonor Lake in Dabzhi (Tib. Mda’ bzhi) to start the shooting. Spending three days with the team enabled me to witness the hyperactivity that characterises such unique moments of crystallization of projects after months of intense preparation. The overall mood was concentrated and relaxed at the same time. Everyone was crammed in bunk beds, in an atmosphere not unlike that of summer camps. Pema had a room for himself, trying to preserve and maintain some serenity and concentration, conducive to good work. He was addressed by his team as “Gen-la” (professor, teacher). They worked hard but with a joyful and friendly atmosphere, with little tension despite the intense schedule. Almost two decades of dedication and inspiration had yielded good results. Back in the early 2000s, Pema had dreamt of a Tibetan cinema that could stand on its feet. Talent, efficiency, commitment as well as a team spirit had borne fruit.

2019 was the last year we were to meet, and fortunately, we had three opportunities to do so. He came over to France with his wife and son. He received for Jinpa the Golden Cycle, the most prestigious award at the Vesoul FICA Asian Film Festival. He happily mixed with French admirers and friends at our university, Inalco, where he was a regular visitor.

Pema Tseden (front, right) signing autographs after the screening of “Silent Holy Stones”, Inalco, February 2019 ©Françoise Robin

Pema Tseden presenting The Silent Holy Stones (2005) at Inalco, Paris, February 2019

The Pema family in the Paris underground, February 2019 ©Françoise Robin

Pema took advantage of that trip to Paris to visit the Cannes Film Festival Paris office, where he had secured a meeting with Christian Jeune, vice-head of the Cannes Film Festival. In the waiting room, Pema confided that he knew his films stood little chance: no terrorism, no violence, no sex, no migration. Christian Jeune welcomed Pema and his family, with a big smile on his face, on the top floor of the building. Although Pema’s films had never been selected at the Cannes Film Festival, he had become an indispensable member of the great world cinema family.

Pema’s family and Christian Jeune (2nd right), vice-head, Cannes Film Festival headquarters, Paris, February 2019 ©Françoise Robin

In July, Pema and I met again, this time on the occasion of the 15th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, held in Paris. Although not a scholar in Tibetan Studies, he was our guest speaker. He accepted our invitation despite his busy schedule—a sign that Tibetan Studies mattered to him. Due to technical problems, we had to show Old Dog instead of Jinpa–a choice that he did not approve of, given the tragic ending of Old Dog always created a steer among the public. Before the screening, he delivered a speech about the importance of maintaining a high standard in Tibetan Studies. He had many university friends in that field and could interact with scholars at ease, always keen to learn new things and deepen his knowledge. His calm demeanour and determination struck many in the audience, who met him for the first time.

Pema (right) and his translator (author of this essay, left), during the plenary session of the 15th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies. July 2019, Paris ©Olivier Adam

During a cruise on the River Seine, 15th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, July 2019, Paris ©Olivier Adam

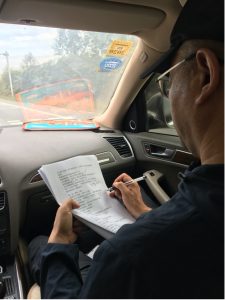

In August of that year, Lhapal Gyal (director of Wangdrak’s Rain Boots) was shooting The Great Distance Delivers Crane (it was to be released in 2021). Pema, who was the executive producer, shared his car with me from Xining to the shooting location. He worked for most of the car ride.

Pema annotating a scenario on the way between Xining and Dabzhi, August 2019 ©Françoise Robin

As on Wangdrak’s Rain Boots shooting, the mood was active, relaxed, and dedicated. The team comprised of, quite stable from one year to the other, a group of young Tibetan-Chinese and Tibetan (mostly) men, all eager to contribute to the emergence of a Tibetan cinema, and several of Pema’s relatives and old friends, equally keen to give a hand.

Pema Tseden in discussion with the staff of Lhapal Gyal’s second film The Great Distance Delivers Crane, August 2019 ©Françoise Robin

We met again one last time in Venice that year, where he was with Jigme Trinley and received an award for Balloon.

Pema Tseden (2nd right), Jigme Trinley (2nd left), a producer from The Factory (right), the author (left), September 2019 ©Françoise Robin

That was the last time we were to meet. He was due to come to France again to preside over the jury of the Vesoul FICA Asian Film Festival in March 2020 but was unable to attend due to the pandemic. During the three years that followed, communication and circulation were difficult between the PRC and the rest of the world.

On 7 May 2023, I joined for an afternoon tea a friend in a Tibetan restaurant in Paris. I slightly erred on my way there and found myself almost in front of the building where I had seen a furious Pierre Rissient, back in 2008, yelling at the then head of the Cannes Film Festival upon learning that Pema’s The Search rejection. I finally made it to the restaurant, intensely thinking of Pema. In the evening, I went to see Howard Hawk’s The Big Sleep, shown at the prestigious French Cinematheque, in the same room as Pema’s Old Dog had been shown back in 2017 during a retrospective dedicated to “News Voices of the Young Chinese Cinema.” At 7:54 pm I took a snapshot of one of the first images of the film, intending to send it to Pema the next day, as a gentle way to say hello. Almost at the same time, he was collapsing on his knees, somewhere in Nakartse, a small Tibetan town. Little did I know that he had entered into his own big sleep…

Screenshot at French Cinémathèque, May 7, 2023, 7:54 pm ©Françoise Robin

The next morning, at around 10:00 am in France, the unbelievable news of his passing reached us. As the People’s Republic of China had opened again to tourism recently, I made a point of returning to Xining and to ask Pema Tseden’s friends what had really happened. Since May 8, rumours were abuzz, but more than rumours, there was silence. Communication is not easy between the PRC and the rest of the world, and it was also too painful a topic to broach over WeChat. Many emails and messages of condolence from friends in France, Europe, and the world had reached my email box, and I wanted to know from first-hand witnesses what had happened to someone only 53 years of age (54 in Tibetan years) and at the apex of his magnificent career. I arrived in Xining in late July 2023. Tsemdo, Pema Tseden’s faithful assistant, agreed to share with me details about what had happened even though it was still painful for him to revive those moments. We met in Pema’s office, Mani Stones Pictures, in the hype western quarter of Xining, the newly developed and hype area where things happen. Tsemdo is now the legal representative of Mani Stones Pictures.

Room with a view: Pema Tseden’s office, Xining, August 2023 ©Françoise Robin

Pema’s room, his tea set untouched, his projects, everything was in neat order. Posters of Pema’s films, some awards, Pema’s films DVD copies and books—a testimony to his busy life—was being stored and archived.

Tsemdo, in Mani Stone Pictures office, Xining, August 2023 ©Françoise Robin

Tsemdo took me to a Tibetan restaurant nearby (where a sign said “It is very good to know many languages, but shameful not to know yours”), and we sat for a good two or three hours. He had been with Pema until his last breath and is a trustworthy witness. I will summarise here our conversation, which he allowed me to share, complementing the already detailed information provided in Dhondup T. Rekjong’s biography.[20]

In December 2022, the PRC government yielded to internal pressure and abruptly eased its harsh anti-COVID measures, mainly strict lockdown. Like many others in the PRC, Pema, who suffered from chronic diabetes and hypertension, caught Covid rather badly. He recovered, but his lung and respiratory functions were possibly undermined, one of the usual aftermaths of COVID-19. For Tibetan New Year, Pema, his wife Yudontso, and their son Jigme, as well as a few Tibetan friends, visited Pema’s mother, an elderly sick woman, in Dzona. Pema then returned to Hanzhou, where he held a position for three years as a professor at the School of Film Art, China Academy of Art (CAA).[21] Hangzhou, on the eastern coast of China, lies at a very low altitude. In April 2024, Jigme Trinley began shooting Karma and the Path (Tib. Las dang lam), his second film after One and Four (Tib. Gcig dang Bzhi, 2021), this time in the Tibet Autonomous Region. It was a road movie, taking place in the Tibet Autonomous Region, in locations far apart (Lhasa, Shigatse, Everest Base camp) and with a substantial crew (over one hundred and twenty people). As was customary, Jigme and his father collaborated, and Pema planned to visit his son and the crew at the site of the shooting. On May 1, Pema flew from Hangzhou to Lhasa. Instead of resting for a few days to get accustomed to high altitude, as most travellers do, Pema, the ever-busy person, immediately drove to Nakartse, a small town by the Yamdrok Yumtso lake (Tib. Yar ’brog g.yu mtsho) at an altitude of 5,200m. Life on a shooting site is extremely busy and people were working tirelessly. Pema, when not on location, worked from his hotel room, revising a script, answering emails, evaluating projects, helping students, reading, etc. Normally, an assistant took care of Pema’s basic needs (food, health, sleeping arrangement), as Pema would tend to neglect these material aspects of life when he was busy on a shooting. Unfortunately, during these last few days, he was by himself. On May 6, Pema went to the Yardrok Yumtso Lake to accompany Jigme, who was directing a few scenes there. At 9:00 pm on May 7, Damchö (Tib. Dam chos), one of the actors in Jigme’s film, asked Tsemdo if Pema could have dinner with him, but Pema had already had dinner and was busy working on a new script. He was fine at that point in time and had taken a walk with one of the Chinese technicians of the crew. On May 8 at 3:00 am, Pema asked Tsemdo to take him to the hospital, as he was feeling unwell. Tsemdo immediately arranged for a car to wait for them at the entrance of the hotel. In the meantime, Pema left a second message to Tsemdo, asking him to bring him oxygen; altitude sickness is common at such an altitude and the crew had kept some in case of need. Tsemdo grabbed two bottles of oxygen downstairs and rushed up to Pema’s room. He saw that the bottle that was already in Pema’s room was empty. He gave oxygen to Pema who, at that point, could talk and walk. Tsemdo helped him downstairs, they entered the car waiting for them and reached the dispensary in a matter of minutes. Upon arrival, although Tsemdo had phoned ahead to request a doctor to be ready, no one was at the gate. Pema got out of the car by himself although he was weak and quiet. He vomited and collapsed. It was a little past 3:30 am, and at that point, Jigme, who was staying at a different hotel, had reached the hospital. The doctor finally opened the hospital door and tried to revive Pema for forty minutes but to no avail. Tsemdo and Jigme tried to have Pema flown by helicopter to Lhasa, but none would take off before dawn. An ambulance with Pema, Jigme, and Pema Dorje (Tib. Padma rdo rje), Pema’s relative who was working on the film, rushed to Lhasa, over 175 km from Nakartse, and Tsemdo, Jinpa and others followed in their cars. They reached the Lhasa People’s Hospital, but Pema was declared dead by the Lhasa doctors at 7:57 am. The consensus is that he suffered from chronic ailments (diabetes, hypertension), had overworked himself over the last two decades, had reached Nakartse too quickly, coming from Hanzhou which is at sea level, had suffered from a lack of oxygen, and after-effects from Covid affected his lung functions. His body was brought to a friend’s home in Lhasa. Incredulous and devastated friends and relatives phoned one another, and many flew to Lhasa to pay him a last visit. On May 10, his body was driven three times around the Jokhang, the holiest of the holiest in the Tibetan world. Then Pema was cremated, and his ashes were brought back to his home village.

A screenshot of a picture of family, friends, and colleagues, gathered in Pema’s hometown on May 13, 2023 (Source: WeChat)

There Tsemdo ended his recollection and summarized: “When he was with us, we never worried. We knew we could call him. This is over.” Other friends, whom I also met last summer in Amdo, told me that when friends and family gathered on the 49th day of Pema’s passing, authorities warned them not to come in numbers and not to share much content on social media. As one friend lamented: “We were his closest friends. Others in Beijing, Chengdu, and elsewhere, all were allowed to gather at their will.”

On the 49th day of Pema’s passing, at Ko’u Monastery (Chentsa), where he had filmed Silent Holy Stones (Source: WeChat)

Like Pema Tseden’s numerous friends, I still find it hard to believe that he is not among us anymore. In a way, the way he left us, so suddenly, echoes the ending of his short stories and films: an open ending, leaving the audience full of questions, and busy elaborating on how to interpret the narrative. An abrupt, undecided ending. What made him leave so quickly, as if in haste? Did he overwork himself? Did he make room for the next generation? What will be his legacy? Will the new generation, which he has fostered, keep the flame and make films? He was optimistic when he said in August 2018 in Xining:

There aren’t many professional Tibetan films yet, but I’m optimistic. We have no economic base, but despite everything, we’ve been able to make several professional films that have been judged good enough to find their place in international cinema, in festivals, and that’s very satisfying. We can now tell Tibetan stories at festivals, on the same level as other films.

To be in the same category as other films, from an artistic point of view, even if there aren’t many of us, is a huge source of satisfaction. All it takes is a handful of these professional Tibetan films. In China, a thousand films are made every year, but that’s not many compared to the total population. Moreover, few of these films find their way onto the screen. Finally, very few of these films are arthouse films, and the number of arthouse films in China is declining. That Tibetan films can be at par with Chinese films in terms of professionalism is a source of satisfaction.

In September 2023, Jigme, Jinpa, and Tseten Tashi came to Venice for the world premiere of Snow Leopard. The team had not recovered their luggage and had to buy suits in Venice at the last minute. The film was very well received among the audience, many of whom were not aware of the tragic passing away of Pema Tseden a few months before. The team was dignified and very moved. Under our friend Mara Matta’s guidance and flair, we took a harassed team to a secluded restaurant with a nice courtyard under the shade of trees, in the Jewish Ghetto. We ordered plates of meat and beer—except for Tseten Tashi, who is a vegetarian. The team could at last relax. Jigme struck me as being as strong as a rock. I asked him how he was coping. He said, “Fine. Sometimes I dream of my father. He tells me—Don’t worry. Everything will be alright.”

Father and son, Paris underground, February 2019 ©Françoise Robin

Works cited

Barnett, Robbie. “Close Encounters of the Filmic Kind: Visualising the Chinese Arrival in Tibet”, in R. Barnett, B. Weiner & F. Robin (eds.), Conflicting Memories. Tibetan History under Mao Retold. Brill, 2020, pp. 141-203. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004433243_007

Frangville, Vanessa. “’Minority Film’ and Tibet in the PRC: From ‘Hell on Earth’ to the ‘Garden of Eden’”. Latse Journal (7), 2012, pp. 8-28.

Frangville, Vanessa. 2020. “’Unity within Diversity’: The Chinese Communist Party’s Construction of the Chinese Nation”, in C. Froissart and J. Doyon (eds.), The Chinese Communist Party: A 100-Ye Trajectory. Australia National University Press, pp. 349-372.

Lhashamgyal. “Tibetans of Beijing”, Asymptote, no date of publication. https://www.asymptotejournal.com/nonfiction/lha-byams-rgyal-tibetans-of-beijing/

Padma Tshe brtan, Bslu brid. Mtsho sngon mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2009.

Rouzhuo (Rigdrol) Jikar. “Syncretism of Tradition and Modernity in Education: A Case Study of a Tibetan Vocational School in Qinghai”, American Behavioral Scientist 2024 68(3): pp. 355–371 DOI: 10.1177/00027642221134839.] https

Weiner, Benno. The Chinese Revolution on the Tibetan Frontier. Cornell University Press, 2020.

Yeh, Emily. Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development. Cornell University Press, 2013, 344 pp.

Yeung, Jessica and Wai-ping Yau. “The Films and Fiction of Pema Tseden”, in Tharlo, Short Story and Film Script, J. Yeung (ed.). MCCM Creations, 2017, pp. 6-57.

Notes

[1] It can be found in Padma tshe brtan 2009: 284-298.

[2] On China-made films about Tibet, see Barnett 2020 and Frangville 2012.

[3] It is now well established that Pema was the first filmmaker in the PRC who insisted upon having full-fledged Tibetan characters performed by Tibetans (not a common feature in the early 2000s) and in the Tibetan language (most PRC Tibet-related films were systematically dubbed into Chinese until then).

[4] Quoted in https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2023/05/remembering-pema-tseden-a-giant-of-filmmaking/

[5] The UNESCO “Fellini Prize”, awarded to personalities who have contributed to the cinema, was granted to him in 2002 for introducing Asian cinema to the Western world. He produced Jane Campion’s The Piano Lesson as well as Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry.

[6] The 2011-2012 issue of Latse Journal was dedicated to Tibetan cinema: https://issuu.com/tracefoundation/docs/latse_issu/1 It includes one article by Pema Tseden about young Tibetan filmmakers, already signalling his attention to the next generation.

[7] https://www.sudouest.fr/thematiques/archives/article9348232.ece

[8] https://yeshe.org/three-photographs-and-the-days-of-my-youth/

[9] Many Amdo men underwent the same fate after the massive anti-Communist uprising that engulfed Amdo in 1958. For a fine historical study of that period, see Weiner 2020.

[10] https://yeshe.org/pema-tseden-the-master

[11] Not to be confused with its synonym on the Tsangpo River, in Central Tibet, where the “Northern Treasures” Nyingma tradition flourished.

[12] Lhalung is the monk who killed in 842 Langdarma, the supposedly anti-Buddhist Tibetan emperor, and then escaped all the way to Amdo.

[13] More generally, no Tibetan-language primary and secondary language education is available in regional capitals outside the TAR, despite substantial Tibetan populations living in towns like Xining, Lanzhou, Chengdu, and repeated requests. Lhashem Gyal the Tibetan writer, and friend of Pema Tseden, has written an essay about the quandary of Tibetans living in Beijing (Lhashamgyal no date of publication)

[14]Rouzhuo 2024: 368.

[15] The wave of de-ethnicization of “ethnic” higher institutes of education has gone unnoticed in the West, but has been confirmed by at least three different reliable sources. This reflects “accelerated assimilationist trends […] emphasising a Han-centred definition of the Chinese nation” (Frangville 2020: 350) since the 2000s and, increasingly so, since Xi Jinping’s access to power in 2012.

[16] On the “gift of development” imposed by the Chinese authorities to Tibetans, as well as the trope of backwardness that often accompanies it, see Yeh 2013.

[17] J. Yeung’s monography about Tharlo provides an excellent introduction and filmic analysis of the film, co-written with Wai-ping Yau.

[18] At almost the same time, Sonthar Gyal had also established “Garuda” (Tib. Khyung), a cinema base in his hometown, Bardzong (Tib. ’Ba’ rdzong, Gad pa sum rdo District, Qinghai). For details, see Robin 2017 (https://highpeakspureearth.com/poem-this-is-how-we-quietly-work-by-gangshun-with-accompanying-essay-by-francoise-robin/). According to Sonthar Gyal, in 2023, it had become a fully-equipped studio and training centre (for sound engineer, light, photography, make-up, editing, props, color grading). It was holding training sessions with professional instructors coming over from Eastern China, and young trainees being sent for further study in mainland China. Sixty persons had registered officially as film-related staff in Bardzong, which represented the highest proportion in the whole of Qinghai (personal communication, July 2023, Xining).

[19] On whom see http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/eyesoftibetan/2015-07/14/content_21709840.htm

[20] https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Pema-Tseden/13816

[21] For a tribute to Pema Tseden emanating from the school, see https://en.caa.edu.cn/news/1032.html

Françoise Robin is a Professor of Tibetan language and literature at Inalco. She specializes in Tibetan contemporary literature and cinema, as well as the emergence of feminism in Tibet. She met Pema Tseden as early as 2002 in Xining, when doing fieldwork about young promising writers. She accompanied him at some festivals as a translator and subtitled most of his films into French. She has also translated a selection of Pema Tseden’s short stories (Neige, 2016), along with Brigitte Duzan. She is the guest editor of the present volume of Yeshe

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities