ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’: An Unfortunate Conceptual Blind Spot for the Tibetans

Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy

Abstract: This article seeks to understand why Tibetans, especially from exile, have not engaged with the concept of ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’ (ICH), a concept that has become dominant in cultural policy not only in the West, but also in the People’s Republic of China since the mid-2000s. It is the written version of a presentation made for Tibetan artists and bureaucrats in Dharamsala, attempting to sum-up the genealogy, aims, language and logic of UNESCO’s categorizations of culture, contextualizing the UNESCO heritage nominations in a comparative worldwide survey. It then explores the political, linguistic and cultural reasons explaining the relative blind spot of ICH among Tibetan communities, before moving to the specific challenges faced by ICH-nominated traditions and artists in Tibet.

Keywords: Intangible Cultural Heritage, UNESCO, cultural categories, concepts of culture, public culture

Introduction

This paper is a polished version of a talk that I delivered in Dharamshala on 8 November 2019, in the days following the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA)’s 60th Anniversary Conference. It was specifically intended for an audience of Tibetan artists and bureaucrats, rather than international scholars. I was asked to give an overall presentation of the concept of ‘intangible cultural heritage’ (ICH), because it refers to policies aimed at preserving songs, dances, dramas and cultural practices–not unlike what TIPA has been attempting to do for six decades–and because some traditions of Tibetan performing arts have been inscribed on UNESCO’s representative list of mankind’s ICH, giving them a new international visibility.

The phrase ICH remains obscure for nearly all Tibetans in exile – actually, as we will see, for most Tibetans in Tibet as well. The terminology has been ubiquitously used in the cultural policies of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since 2006, and it has given rise all over the country, and especially among the so-called ‘ethnic minorities’ (Ch. shaoshu minzu), to a massive output of lavishly funded state programs, festivals, museums, academic conferences, books, DVDs and commercial by-products for tourism. Conversely, the concept is never used in official discourse in exile and is virtually ignored in colloquial speech—a noted exception being Tibetan scholars and artists concerned with cultural loss and preservation who have been trained at colleges in the West. More critically, in 2009, the inscription of three Tibetan artistic practices on UNESCO’s ICH Representative List, endorsing the PRC’s applications and placing them under the umbrella ‘heritage of China’, hardly raised an eyebrow among Tibetan exiles.[i] A few years later, the ICH concept did somewhat percolate among some exile Tibetans, in discussions about Tibetan medicine, but the term ICH was immediately dismissed: Tibetan physicians felt that medicine could not be adequately included in the category of ICH.[ii] The issue grew despite them, however, as the PRC and the Indian government entered a tug-of-war over the nomination of Tibetan medicine (termed ‘sowa rigpa’[iii] in the application) as a global UNESCO ICH. The Indian government stepped in to defend what it saw as an ‘Indian’ heritage, officially because of Buddhism and because of all the non-Tibetan physicians practising this medical system in the Himalayan fringes of India–more practically because of the huge economic stakes involved in the local production and global consumption of Tibetan medicine, stakes that are unmatched by the less-sellable ‘performing arts’. Eventually, in 2018 China won the inscription of the “lum medicinal bathing of sowa rigpa” as a ‘Chinese’ world heritage.[iv] At that juncture, once again, there was no officially reported response among Tibetan exiles, from either physicians or politicians.

In Tibetan areas of the PRC, despite the pervasive mobilization of ICH terminology by the government in the management of Tibetan culture over the last 15 years, and its ever-presence in official discourse, the idiom remains obstinately abstract for the great majority of Tibetans, even for those who are involved in ICH… and sometimes even for the local Chinese administrators in charge of the programmes. Why has this strategic concept, with so much political, economic and mediatic leverage, been left in the shade of ignorance by Tibetans? In this paper, I will propose that this obliviousness, which is actually far from being limited to Tibetans, can be attributed to a number of reasons, chiefly political, but also linguistic and cultural.

The main purpose of this paper is to clarify what the concept of ICH is about, its genealogy not only in Western thought, but decisively in East Asian views. I will also look at the implicit understandings of ‘culture’, ‘cultural transmission’ and ‘identity’ that it carries, as well as its significance in cultural policy and management in Tibetan areas of the PRC – again, this is not specific to Tibet, as it extends all over China, but the implications are more critical among the so called ‘ethnic minorities’. The following sections will present a compilation of broad ideas, never losing sight that ICH is actually layered with complexity among Tibetans, who have diverse levels of knowledge about, and different types of engagement with the concept. It cannot be easily spurned as yet another rhetorical tool of Sinicization and cultural assimilation in the hands of the PRC government. Occasionally, it does allow for manoeuvring and promoting Tibetan culture by astute stakeholders.

Genealogical overview: Heritage vs. cultural heritage

I apologize for my adopting a somewhat pedagogical tone here, but since ICH seems so remote for many Tibetan audiences, I will work to deliver a brief genealogy of the Western concept by setting it first in a very general historical and cultural context (see also Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 2004). As is well known, ‘the West’ is not culturally homogeneous: from a European’s point of view, people hailing from different European countries feel strongly that they have different cultures and histories, not to mention different languages. Tibetans in this part of the world[v] have been mostly exposed to an English-speaking educational background derived from the British colonial empire and its aftermath. It is important to underline that the concept of ‘heritage’ that will concern us here does not stem from this cultural background, but first emerged in France (where UNESCO headquarters are presently located). After retracing the genealogy of the concept, I will move onto its use and understanding by UNESCO.

The basic idea behind the notion of ‘heritage’ is that from the 18th century onwards, some European States have decided that selected collective realizations were of outstanding collective value because of their emblematic relationship with collective history or their sheer rarity, and that they should not belong to a private party, or to the ruler, but rather to all community members equally. Their custodian would be a public body, to ensure (what would later be called) their ‘preservation’ (U.S. terminology) or ‘conservation’ (U.K.), so that they could be passed down onto future generations.

Because of this specific focus on public stewardship and transmission, it is distinct from ‘collecting’, a millennia-old practice that consists in planning thematic collections of objects for either hoarding or exhibition purposes. Already in the 3rd millennium BC, for example, the royalty and elites of Mesopotamia ostensibly collected objects of luxury (Thomason 2005). In ancient Egypt, Ptolemy II (3rd century BC) and his successors collected books from all over the known world in the famous library of Alexandria. In Asia as well, successive Indian and Chinese political rulers have repeatedly constituted their own private collections. Closer to our time, but before the formation of the modern nation-state, we learn that during the Italian Renaissance, the Medici family in Florence (15th century) became the private patrons of a huge collection of art masterpieces and supported the local painters in their ground-breaking renewal of the aesthetic codes of Western art. From the 16th century onwards, with the intensification of colonial pilfering, several members of the European royalty and some European scholars developed a new hobby, that of piling up the strange natural and ethnographic objects brought back from the conquered lands into ‘cabinets of curiosities’, also known as Studiolo in Italy or Wunderkammer in Germany. These objects formed collections that would become precursors of the modern ‘museums’ from the 19th century onwards. This brings us to the period of industrialization and the development of the bourgeoisie, when a larger number of people started private collections for leisure, often focusing on home decoration items.

The idea of public ‘heritage’ is thus quite distinct from collecting and it seems that it emerged in France in the late 18th century, in the wake of the massive destructions of the French Revolution in 1789.[vi] There had been one or two forerunners in France a century earlier, who catalogued the surviving Catholic monuments, manuscripts and art pieces of the Middle Ages, fearing their quick disappearance, but without any public service to bring together or protect these objects. This process is also set in a wider cultural shift, that had been taking place over the previous two or three centuries: from the Italian Renaissance onwards (15th century), with the rediscovery of the vestiges of the Greek and Roman antiquity (5th century BC to 5th century AD), new ideas about Europe (perhaps more aptly, the Mediterranean)’s rich past emerged, a past that was at the same time glorious and non-Christian, disputing the Catholic religion’s total grip over knowledge and attitudes over the last millennium. New ideas about history, and about what we would today call ‘identity’, had thus been brewing for some time in Europe when the French Revolutionaries engineered the demolition of the Ancien Régime. As early as 1789, the properties of the fallen monarchy and Catholic clergy were put under the protection of the ‘Nation’. “Belonging to no-one but owned by all”, they became ‘national objects’, looked after by “all good citizens”. New legal tools were developed, such as new types of decrees and new institutions devoted to collecting and storing threatened artefacts. But the attention was primarily focused on books and manuscripts (for the instruction of ‘the people’), and paintings and sculptures (easy to carry around), neglecting architecture. From its inception, the idea of ‘heritage’ is thus closely linked to nationalism: the constitution of collections owned and managed by a specific community (the Nation-State) that shares (or is made to believe that it shares) a common symbolic relationship to these objects.[vii]

The idea that some human realizations belong not to a Nation in particular but rather to the whole of humanity, is a much later development. It slowly emerged in the mid-20th century, after the devastation of the Second World War, first with the founding of UNESCO in 1945, then with the signing of its landmark ‘Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage’ in 1972 (implemented in 1975, signed by 193 States). This was the culmination of decades of lobbying to force States to take responsibility (that is, to invest money and devise institutional programmes) to actively protect remarkable items located within their borders.

Four important comments need to be made here. First, we see that the idea of ‘heritage’ evolved. The former implicit understanding of ‘heritage’ as man-made, now branched off into a double conceptualization of heritage as either ‘cultural’ or ‘natural’. ‘Cultural’ heritage referred to material artefacts such as architecture (churches/temples, palaces, mansions), art pieces (paintings, statues, medals, trophies), coins, manuscripts, working tools, and more generally, all aspects of material culture (cloth, weaving, jewels, home decorations…). ‘Natural’ heritage referred to outstanding features of the landscape or remarkable zones of biodiversity (in flora and fauna) and geological diversity (unique rock formations). To make matters more complicated, some sites have been deemed “mixed’, both cultural and natural, such as Machu Picchu in Peru, or Mount Emei in China.

Second, the notion of heritage claims to address valuable elements of mankind as a whole, but as with other universalist concepts (such as human rights), it is rooted in Western thought and its political model of liberal democracy. However, non-Western signatories of the Convention very soon stepped into the game, and although they do not hail from democracies, they have seen a keen advantage at applying for the various global labels offered by UNESCO. The boosting of the tourism industry is certainly not unrelated to this development.

Third, the very idea of ‘heritage’ in the West came up as a sort of nostalgic look at the past, when it was already ‘too late’, that is, when the cultures supporting these objects were in a great part defunct. Moreover, this nostalgia is imbued with a nationalistic flavour, in the sense that these traditions on the verge of being lost are deemed essential in the shaping of a national bond and belonging. It may be the case that Tibetans feel that their traditions are lively enough that they do not need an objectifying label such as ‘heritage’. But the very idea of the creation of (what would later be called) the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts in 1959 draws exactly from that same double logic of nostalgia and nationalism.

The last remark is of crucial importance for the Tibetans: UNESCO, like other less emblematic institutions devoted to heritage protection,[viii] is intergovernmental. That means that UNESCO, as its first two letters indicate (United Nations) is a dialogue platform between governments. Although the issues are in principle discussed for the good of mankind as a whole, the actual working of this institution (nominations, regulations for the management of heritage items, financial support) happens at the level of States. Cultural regions or stateless diasporas, even those (formerly) seeking self-determination are not internationally recognized governments and therefore are not heard in this assembly, unless they can secure a representation by a full-fledged State submitting an application concerning their tradition (see for example flamenco, recognized at UNESCO as a Spanish heritage, but actually a tradition of the Roma, also known as gypsies, a stateless diasporic community).

Over time, the notion of heritage continued to evolve and broaden. The initial success of the Convention in the 1970s unleashed a passion for the past, especially in the context of rapidly changing industrial societies. Gradually, nearly every mark of human activity has been able to qualify for a ‘heritage’ label: cities as a whole (250, among which Bhaktapur and Lalitpur in Nepal; Jaipur, Vellore, Ahmedabad and Gwalior in India; or Chengde, Lijiang, Macau, Pingyao and Suzhou in China), landscapes (114, among which the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka in India, the mount Wutai in China, or the Orkhon valley in Mongolia), run-down industrial factories, ecological systems, everyday design objects, flowers, and even genetic codes… Two interwoven factors explain this popularity and enlargement: globalization and nostalgia. Celebrating unique local features on the world stage boosts pride, nationalism and regionalism; it secures a worldwide recognition that can be decisive in less affluent countries, especially those where cultural self-esteem has been severely damaged by decades of colonization or dependency. Heritage labels appear as promising new yields through tourism, new avenues for self-affirmation, new ways to fight against the erosion of cultural diversity.

On the other hand, with the rapid ecological and cultural changes brought about by globalization, heritage is valued as a dear memory of days gone by. In this nostalgic contemplation of what the world once was—as well as imagined spaces of what could have been were it not for the vicissitudes of historical realities in the case of former empires (consider Mongolia as a case in point, as well as the maritime Portuguese empire)—and in a context of growing uncertainty vis-à-vis the future, the past appears to be not only a meaningful landmark but also a potential economic resource (Logan 2002, Harrison 2010).

‘Intangible’ cultural heritage

As the notion of ‘cultural heritage’ developed at UNESCO to encompass broader aspects of culture, the connection between culture and collective identity appeared stronger (Ashworth 1994). The most recent development of cultural heritage is the creation of another subcategory: ‘intangible’ heritage, hinting at the non-material dimensions of cultural production and transmission. This is probably the most challenging idea to receive acceptance from Tibetans. An important element to keep in mind is that this extension, or concept, of the ‘intangible’ is not solely ‘Western’.[ix] It is inspired from East Asian conceptions as well: Japan (who joined UNESCO only in 1991) pushed to reform UNESCO’s understanding of ‘culture’[x] to include what it called ‘intangible’ aspects of culture and notions of ‘authenticity’ closer to its values (‘excellence’, or ‘being outstanding’ mattering more than perpetuating an unbroken lineage of practice). In 1993, South Korea also recommended to UNESCO its ‘living human treasures’ system, where important performers are enticed to transmit their knowledge to the next generation in exchange of a title and stipend. UNESCO’s ICH terminology and programmes thus emerged from critiques stemming from East Asia.

The ICH programme took shape gradually. Throughout the 1980s, there were discussions at various UNESCO meetings to include aspects of ‘folklore’, such as music, storytelling or carnivals in the definition of cultural heritage. These ‘living’ traditions were recognized as being as important as, if not more important than, material artefacts (monuments, art works,…) in the shaping of collective identity and a feeling of belonging. In 1997, UNESCO launched its first program labelled ‘Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’, which proclaimed a total of 90 masterpieces over the course of three meetings (2001, 2003, 2005). This first batch of proclamations include, for example: kunqu opera (2001), guqin music (2003) and Uyghur muqam music (2005) in China ; Drametse Ngacham in Bhutan (2005); Kutiyattam Sanskrit theatre (2001), Vedic chanting (2003) and the Ramlila Ramayana Performance (2005) in India; as well as the morin khuur music (2003) and the urtiin duu long song (2005) in Mongolia.

This first programme was met with strong criticism by some member states: the ‘Masterpieces’ project was thought to promote an elitist notion of culture (the vocabulary was then toned down from ‘outstanding’ to ‘representative’ examples of community culture); it did not have much administrative or financial support; a community-based participatory approach was put forward as the best way to safeguard intangible culture; and finally there was a growing concern about the ‘cultural rights’ (a subcategory of human rights) of the performers involved. These criticisms led to another reform, culminating in 2003 with the signing by 178 States of the ‘Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage’, which took effect in 2006.

The first system of ‘proclamations’ was replaced with, and included into a dual list system: the ‘Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ (most elements), and the ‘List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding’ (fewer elements in a dire condition; China has nine such inscriptions, including the Qiang New Year Festival in 2009 and the Meshrep of the Uyghurs in 2010). Since 2008, UNESCO has held annual (rather than biennial) meetings to make new inscriptions. A third category put forth by UNESCO is the ‘Register for Good Safeguarding Practices’, which allows States, communities and other stakeholders to “share successful safeguarding experiences and examples of how they surmounted challenges faced in the transmission of their living heritage, its practice and knowledge to the future generation” (UNESCO website). Out of the 25 items in this category,[xi] China was inscribed in 2012 for its ‘Strategy for training coming generations of Fujian puppetry practitioners’. Altogether, as of 2020, there are 584 items from 131 countries inscribed on UNESCO’s three ICH lists (see statistics in the next section). The Convention explicitly lists the five “domains” of ICH:[xii]

- Oral history, oral traditions and expressions, including language;

- Performing arts;

- Social practices, food, rituals and festive events;

- Knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; and

- Traditional craftsmanship.

As we see, the scope is much larger than songs and dances, although the first two domains of this list certainly hold the largest number of items. Carnivals and community rituals feature in the third domain. The concept of ICH also stretches to include, in the fourth and fifth domains, systems of knowledge. The knowledge and wisdom concerned here can be spiritual, as with the beliefs and practices of Amazonian shamans in Colombia (2011) or young men puberty initiation rituals in Mali (2011) and Kenya (2018). It can also encompass scientific knowledge, as with acupuncture (2010) and the abacus from China (2013); or a cross-over of spirituality and science with yoga (India, 2016) and taijiquan (China, 2020). This is why Tibetan medical knowledge, although very practical and material from a local physician’s point of view, is eligible for the ICH category.[xiii] Due to the political tensions between India and China, only part of the system was inscribed at UNESCO in 2018, but the full label awarded to China does leave the door open for further inclusion into the UNESCO inscription: “Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa, knowledge and practices concerning life, health and illness prevention and treatment among the Tibetan people in China”. China was not awarded the full nomination of sowa rigpa in 2020. With India stepping up its game, the future will tell how this story will unfold…

UNESCO Heritage nominations: Globally and in the greater Tibetan and Himalayan world

Before zooming in on those heritage nominations that are close to home for the Tibetan readership of this paper, let us first establish a general sense of what may be at stake by perusing UNESCO nominations’ statistics. World Heritage The following information stems from UNESCO’s website.[xiv] In total, there are 1121 items that have received the organization’s ‘world heritage’ label, during yearly assemblies that have been held uninterruptedly since 1978; and 167 State parties are involved in protecting heritage within their boundaries. This does not include ICH (180 signatory States), which is listed in a separate category (see Figures 4 and 5 below). One has to keep in mind that the various commissions dealing with ‘World Heritage’ (nominating cities, landscapes, sites,…) are regrouped under the ‘World Heritage Centre’ website, which is separate from the Intangible Cultural Heritage website.[xv]

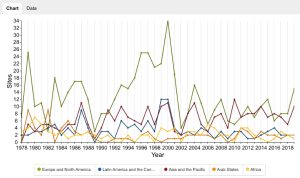

Figure 1 provides a longitudinal image of the number of world heritage ‘properties’ (UNESCO’s terminology) per year (up to 2019) and per ‘region’ (again, quoting from UNESCO’s terminology; these regions do not appear to make much sense from an anthropological, let alone historical, viewpoint). We can see a regular pattern of Europe and North America towering over the other regions (with a peak in 2000), followed by Asia and the Pacific, then Latin America, and leaving mere crumbs to Arab States and Africa.

Figure 1: Number of World Heritage properties inscribed each year by region (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/stat)

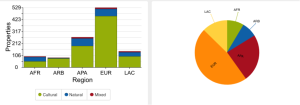

Figure 2 gives a more precise overview of the regional shares, where we see that Europe and North America account for nearly half of all properties. This figure also provides complementary information about which type of ‘heritage’ is entailed, and whether each is (from top to bottom) cultural, natural, or mixed. We see that, everywhere in the world, cultural heritage is the dominant form of heritage, but natural heritage items seem proportionately most numerous in the Asia and Pacific region.

Figure 2: Number of World Heritage Properties by region (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/stat). From left to right: Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and North America, Asia and the Pacific, Arab States and Africa.

Figure 3 gives an overall sense of world heritage properties. Out of 1121 items, 869 listings (77%) are cultural, while 213 items (19%) are natural and 39 are mixed. Of note here are the 39 items that are ‘transboundary’ (20 cultural, 16 natural, 3 mixed), i.e. co-managed by different States. In this last category we find, “Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor” (since 2014), involving the cooperation of China, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan; and the urtiin duu, the traditional folk long song genre jointly managed by China and Mongolia.

An important category is the one that lists 53 properties in danger (36 cultural, 17 natural), either because they are in countries torn by conflict (the Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan, all 6 items from Syria, the old city of Jerusalem…), or because of economic development (the historic centre of Vienna in Austria), or finally because of the shrinking of rain forests and wildlife reserves. No world heritage properties in danger have been noted in China, India, or Nepal. Many sites are, however, under close surveillance. Lastly, two properties have been delisted by UNESCO: the Dresden Elbe valley in Germany (cultural site listed in 2004, delisted in 2009 because of the construction of a modern four-lane-bridge in the middle of the site, ruining its historic value) and the Arabian Oryx sanctuary in the sultanate of Oman (natural site listed in 1994 devoted to a rare species of gazella, delisted in 2007 because of Oman’s decision to reduce the site by 90% to favour commercial ventures; the gazella is now nearly extinct because of poaching and habitat degradation).

Figure 3: Overall World heritage list (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/)

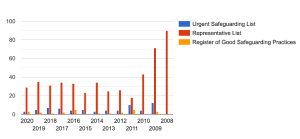

Figures 4 and 5 deal exclusively with Intangible Cultural Heritage. Figure 4 shows the evolution of the number of ICH labels since 2008 (chronologically, from right to left). It starts from 2008 onwards, the year when the first batch of UNESCO’s ICH proclamations (‘Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’) was replaced with the two-list system: the ‘Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’ and the ‘List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding’, plus the “Register for Good Safeguarding Practices’ (see section above).

Figure 4: Number of inscriptions on UNESCO’s ICH list, reading chronologically from right to left. (https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists?multinational=3&display1=inscriptionID&display=stats#tabs)

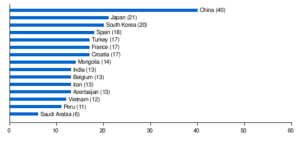

Figure 5 presents the Intangible Cultural Heritage listings per country, as per 2019. With annual nominations since 2008, there are now overall 584 elements inscribed, representing 131 countries. As we can see, East Asia, and especially China, are towering over the statistics. These 584 elements comprise 492 items on the ‘Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity’, 67 items on the ‘List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding’, and 25 items on the “Register for Good Safeguarding Practices’. It is interesting to note that out of the 67 items in need of urgent safeguarding, 7 are from China (including textile or printing techniques, as well as the Qiang New Year Festival and the Uyghur Meshrep for non-Han peoples); and 7 are from Mongolia (including various music traditions, the epic, a folk dance style, long song and calligraphy).

Figure 5: Number on inscriptions on UNESCO’s ICH lists per country (https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists?text=&multinational=3&display1=inscriptionID#tabs)

After this statistical portrayal of overall UNESCO listings, let us take a closer look at heritage inscriptions hailing from the greater Tibetan and Himalayan region, to bring the paper closer to familiar terrain. I shall divide the findings from the UNESCO website by using the cultural, natural and intangible categories of UNESCO.

- The first and only cultural heritage designation in Tibet is perhaps its most famous: the Potala palace in Lhasa, inscribed in 1994, then extended to include (strangely under the same label) the Potala Palace, the Jokhang and the Norbulingka palace area – three of the most revered pilgrimage sites, but which are scattered across the Tibetan capital.

- Five remarkable natural heritage designations include, chronologically: the Sichuan Panda sanctuaries in China (Wolong, Mt Siguniang and Jiajin Mountains; in 2006); the transboundary site named ‘Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor’ (co-managed by China, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, 2014), the Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area (in Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014), the Khangchendzonga National Park (Sikkim, India, 2016), and finally the Qinghai Hoh xil (in Qinghai province, China, 2017), made famous after Lu Chuan’s popular movie Kekexili Moutain Patrol (可可西里, 2004), about Tibetan vigilante rangers protecting wild antelopes.

- There are six listings in the ‘Representative list of Intangible Cultural Heritage’ category. First, the Bhutanese Drametse ngacham (2005) looks to me very close to the tsechu, or 10th day ritual monastic dance on the Tibetan side of the border. Then, three traditions were promoted simultaneously in 2009 for China: the Gesar epic, Tibetan Opera or ache lhamo, and what is called by UNESCO ‘Regong arts’, referring to the thangka painting tradition of Sengeshong, a village inhabited by ethnically Monguor people (土族Tuzu in Chinese), speaking Wutun (a language mixing Mandarin, Mongolian and Tibetan), in the vicinity of Rebgong in Qinghai. Fifth, the ‘Buddhist chanting of Ladakh: recitation of sacred Buddhist texts in the trans-Himalayan Ladakh region’ was proclaimed for India in 2012 and covers Tibetan Buddhist chanting from all sectarian lineages in Ladakh, virtually undistinguishable from Tibetan standard religious practice. Finally, as mentioned before, China won the listing of the ‘lum medicinal bath of sowa rigpa’ in 2018. As of 2020, the governments of India and China are once again fighting for a recognition of the whole tradition of ‘sowa rigpa’ under their sole tutelage for UNESCO’s next round of ICH inscriptions.

A particular view of ‘culture’ embedded in the ICH concept

One of the possible reasons why ICH is a conceptual blind spot for Tibetans is that it carries an implicit understanding of ‘culture’ that may feel remote to Tibetans as they relate to their own notion of ‘culture’ (rigne). As I have tried to show above, ‘cultural heritage’, and in particular ‘intangible cultural heritage’ are intrinsically linked to an instrumental, more precisely nationalistic, view of culture (Harrison 2010). Flamenco for gypsies in Spain, acupuncture and taijiquan in China, ache lhamo or the Gesar epic for Tibetans… these are metonyms, or illustrative vignettes of ‘culture’, sometimes of ‘invented traditions’ (Hobsbawm & Ranger 1983), that are so well-known across the whole social spectrum of a community, and encapsulate so many cultural referents at once, that they serve to ‘represent’ the whole nation in the eyes of outsiders (Smith 2006). In the age of The Society of the Spectacle (Debord 1970), culture has become a matter of spectacle, representation, ‘exhibition’ (Denton 2005, 2014), rather than a deep source of history, knowledge, or wisdom that informs the individuals who grow in it, or with it. Culture has become politicised and reified in essentialised and simplified images that shape collective identity and a sense of belonging. Folk music and dance, although they seem anecdotal and ‘not serious’ in Tibetan society, actually constitute the common language in which nations see and relate to each other. Folklore has played a crucial role in the constitution of the ways in which nations are recognised as legitimate (Bronner 1998, Hafstein 2007, Harrison 2010, Brosius and Polit 2011).

This politicised ‘catalogue’ view of culture is also remote from how anthropologists understand culture: as ever adaptive and organically articulated in the multiple layers of the lives of people (Kurin 2004, Arizpe 2013). This is actually one of the many criticisms that ICH programmes have received over time, by academics as well as by stakeholders (Smith and Akagawa 2009, 2019). It can be worthwhile to evoke briefly here other frequent criticisms of ICH policy. First, although ICH programmes try, in principle, to sustain the whole context (economic and social dimensions of artistic and ritual traditions) that give life to an ‘intangible’ tradition, the recurrent effect of ICH proclamations is that they, in effect, isolate the practice from its context, and lead to its further endangerment. Second, it is unclear how States and institutional bodies can safeguard a cultural practice by force, particularly if there is insufficient interest from local practitioners. The last three criticisms (#3, 4 and 5) are the most significant for Tibetans. Third, ICH labels boost tourism and cultural industries, inducing an increased commodification, but the benefiters of the boon are often intermediaries or third parties, so that the original communities producing these ICH practices often end up economically marginalized. Fourth is the crucial issue of cultural ownership. At the level of UNESCO, States are considered the legitimate custodians, managers, and safeguarding agents of the ICH practices proclaimed within their borders. But the issue is sensitive for so-called ethnic minorities, who often end up further dispossessed of their own history and culture. Fifth, it is not because an item is proclaimed as ICH that it is effectively protected by the designated State. There have been stories of irresponsible attitudes of States in the handling of their heritage properties. But there are certain designated tools to make them accountable: States have to send yearly reports to UNESCO on the measures taken and their effects. In case of mismanagement, ICH awards can be revoked, as mentioned above about the Dresden Elbe Valley in Germany and the Arabian Oryx sanctuary in Oman.

To conclude this brief overview, I shall reflect on three possible reasons for Tibetans’ difficulties with the concept of ICH: linguistic, cultural and political. First, merely from the point of view of language, ‘intangible culture heritage’ is an opaque neologism for Tibetans, that has moreover two homophonic spellings .[xvi] Ngöme rigne shülshag (often shortened to ngöme shülshag) is a translation from the Chinese (feiwuzhi wenhua yichan 非物质文化遗产), but two spellings are found : the first two syllables are either spelled mngon-med (unseen, unmanifested) as is found in the first wave of PRC documents in the early 2000s,[xvii] or dngos-med (non-material) in later documents, and this seems to be the standard spelling used in Tibetan publications in the PRC nowadays. The Chinese expression is itself a translation of the English, itself stemming from Japanese ideas that are not immediately clear to an English audience. It is fair to say that in this long line, the meaning got a little lost in translation. Ngöme, ‘non-material’, has connotations of ethereality and transience that do not sit well with how performing cultures are lived and felt among Tibetans.

Second, cultural reluctance to the concept of ICH can be seen in two ways. On one hand, despite strong assaults on Tibetan culture that some authors have termed ‘cultural genocide’ or ‘assimilation’, aspects of Tibetan of culture are still felt by Tibetans as being very strong and alive. Tibetans do not easily identify with a nostalgic contemplation of ‘culture’ in terms of the ways in which it is embedded in ICH and UNESCO objectified conceptions. For most Tibetans, culture is not (yet) something distant, staged, or at least it is not only that. On the other hand, another cultural reluctance may concern the very notion of ‘culture’. ICH presupposes a democratic, or rather a ‘people’s view’ of culture, where ‘culture’ is that everyday life content which is shared by most people. This differs from an elevated and exclusive conception of ‘culture’ (rig gnas) by Tibetans, that carries connotations of virtuous knowledge transmitted by role models. The idea of honouring ‘simple’ singers, dancers or ache lhamo performers as cultural heroes of the community seems odd to most conservative Tibetans. Prestigious seats at official functions are meant for ‘cultural heroes’ that inspire devotion and respect, such as lamas, politicians, and more recently (in exile) resistance fighters who bravely confronted the enemy. In a deeply religious and perhaps exclusive diasporic society, where the very survival of the community rests upon keeping the culture homogenized and extolling role models, the idea to give money, titles, and public acknowledgement to ‘simple’ TIPA artists (if we consider Tibetan exiles) seems at best out of place, if not outright unacceptable. Finally, the third possible reluctance I see of Tibetans with the ICH concept is political. For those who are informed, they know that UNESCO is a cenacle of recognized independent States, and that Tibetans, not having this legitimacy, do not stand much of a chance to be heard, so why bother?

Intangible cultural heritage in the PRC, with a focus on Tibetan areas

After this broad discussion about ICH on the global stage, let us now turn to see how it translates within the PRC in a more detailed way. After the radical socialist decades (1949-late 1970s) when traditional cultures were summarily condemned as ‘backward’ or ‘feudal’ and largely destroyed, the Party-State made a U-turn and started promoting selected traditions. China joined UNESCO and its Conventions in 1985, thereby appropriating the overall value frame of world heritage, an opportunity to show China’s outstanding contribution to humanity and earn international recognition and respect (Hevia 2001, Bodolec 2014).[xviii] However, it selectively appropriated values that were congruent with the CCP’s understanding of ‘people’s culture’ (fostering identity and social cohesion) and how it should remain under the tutelage of the State (Maags and Svensson 2018). But, especially since China’s signing of the ICH convention in 2003 (ratified in 2006), it allowed people to celebrate again their country’s cultural past, leading to a Chinese ‘Renaissance’ of sorts. A renewed historical valuation of the original ‘Middle Kingdom’ was developed and promoted. The State’s push for heritage, whether natural, material-cultural or intangible-cultural, met with very enthusiastic support in the society, resulting in a ‘heritage fever’ (遗产热 yichan re) that has been ongoing for the last 15 years (Yan 2016, 2018). Heritage has since given rise to a huge amount of academic research both in China and in the West. Publications in China tend to extoll the beauty of local traditions and present the researchers as guides for the development of local heritage projects. Publications in the West, by Chinese or Western researchers, tend to be critical of the instrumentalisation of the notion by the government and the adverse effects brought about by heritage labels. The government strategically cultivated the heritage fever for both political and economic reasons. It sought to enhance its legitimacy, both nationally (Blumenfield & Silverman 2013, Yan 2016, Maags and Svensson 2018) and on the international stage (Bodolec 2014, Yan 2016), and it aligned heritage discourse with other political slogans such as Hu Jintao’s ‘harmonious society’ (2010), and Xi Jinping’s ‘Chinese Dream’ (2013) and ‘Revitalize China’s Cultural Confidence’ (2016). Together, they build a seamless narrative continuity that also restates a Han-centred ‘multi-ethnic State’, where ethnic minority traditions are merely decorative. In this way, heritage policy legitimized afresh the extant ethnic minority policies, for example in Tibet (Shepherd 2006, 2009, 2013). Apart from its interests in social stability and ethnic governance, the government also fostered through ‘heritage’ the development of tourism and cultural industries, a frenzy that would occupy a huge place in consumption and in the media. The heritage craze, at the confluence of State and civil society support, allowed for the rejuvenation of the nation with a refurbished but glorious Chinese past (Zhu & Maags, 2020). Research in the West also denounces the commodification of heritage-ized traditions in watered-down or kitsch displays (Shepherd & Yu 2013, Saxer 2012, Zan & Baraldi, 2012). Fewer studies show how heritage policies can occasionally empower local groups (Oakes 2012, D’Evelyn 2018, Rees 2018), through cottage industries, and local cultural performances staged for domestic tourists, trading on their ICH recognition.

Amidst the plethora of discussions on heritage in China, this short section will be limited to intangible cultural heritage, already a layered and complex set of knots. As noted above, the phrase ICH has been translated literally from English into Chinese as feiwuzhi wenhua yichan (非物质文化遗产), a neologism commonly abbreviated to feiyi. As with the other East Asian countries (Japan, South Korea) that had pushed for UNESCO to include immaterial dimensions of culture, China’s own understanding and implementation of ICH emphasises the ‘outstanding value’ of specific traditions (thereby ranking traditions), rather than assessing their ‘authenticity’, a criterion that appears so essential in Western conceptions. In order to understand the pervasiveness of the ICH system in China, it is important to keep in mind that, after the PRC signed the UNESCO ICH Convention in 2003, it launched its own parallel national ICH program in 2005, taking effect in 2006. On the ground, to the people involved in China, it is this national programme, rather than UNESCO’s proclamations on the global stage, that are most meaningful. In Tibetan areas of the PRC, some artists I met were unaware that their traditions had also been inscribed at the international UNESCO level, and only knew about the Chinese system. The PRC aims to be a very centralized State, but the national ICH programme has been launched through a variety of national and local agencies, not through a potential centralized ‘Office for Heritage’, for example: ICH terminology appears in the official documents hailing from the departments of propaganda, culture, education, tourism and economy, all with specific budget lines and promotion teams devoted to ICH. There are, however, devoted ICH offices (generally subsidiaries of departments of culture), which organize the official identification process of ICH items. This identification follows closely the administrative levels of power of the PRC State: nominated items can receive either a county-level award, a prefecture (or municipality[xix])-level award, a province-level (regional-level in the TAR) award or, for the most prestigious and ‘outstanding’ traditions, a national-level ICH award – some items can also be pushed up the administrative ladder, if they are deemed more valuable and, most importantly, if bureaucrats are willing to engage in persistent lobbying. Each level of adjudication has its own identification commission, and there is apparently a lot of corruption when trying to get a promotion to the next administrative level. The higher up in the ladder, the higher the stipend for the performers and the heavier the duties to represent publicly one’s tradition—through countless interviews in the official media, for example, or by sitting at various functions. Furthermore, given the significant commodification of ICH items for tourism and consumption purposes, the private sector is heavily involved in ICH promotion. Therefore, ICH procedures in China (including Tibet) navigate in a grey zone involving both State and private actors (see also Thurston 2019-a-b), adding to its analytical complexity.

Given my area of specialization, I will discuss here more specifically those ICH items associated with the performing arts and in Tibetan areas. Academic research on the processes and effects of heritage in Tibet is still scant: Shepherd (2006, 2009, 2013 (& Yu), 2014, 2017) offers foundational critical reflections on the political use of ‘heritage’ to further the marginalization and dispossession of Tibetan culture, discussing mostly the Potala. Mountcastle (2010) builds on similar critical lines, not based on fieldwork but looking at how the notion of culture is constructed differently in the policies of UNESCO and the PRC State.

Saxer (2012) and Wojahn (2016) have discussed heritage policy. Schrempf (2016, 2017) has looked at medicine, while Gauthard (2011) and Thurston (2019 a-b) have observed Gesar bards in Qinghai, as did documentary filmmaker Donagh Coleman (with Lharigtso) with the informative documentary A Gesar Bard’s Tale (2014). Wojahn (2016) and Henrion-Dourcy (2016) have considered ache lhamo, while Harris (2012) and Sangye Dondhup (2017) provide useful discussions of ‘heritage’ in Tibet. As I have not been granted access to undertake a detailed ethnographic research on this topic in Tibetan areas of the PRC (especially the Tibet Autonomous Region, TAR), here I will make brief points stemming from well-known public information and informal interviews with Tibetan ICH stakeholders carried out in China outside Tibetan areas. As mentioned before, the ICH concept has been yet another tool of culture management for the government, magnifying the effects of previous cultural assimilationist policies and State interventions into ‘folk culture’. ICH programmes came about in a situation where performing arts traditions had already been heavily reworked through State-run programmes during the previous six decades.[xx]

Five chronological periods can be singled out, not distinct from each other, but rather dovetailing with each other, since the effects of the previous periods continue to run into the next period. They can be summarized very briefly (see Henrion-Dourcy 2019 for more details). First, radical Maoism (1949-end of the 1970s) brought an ideological purge of superstition, religion, and elite culture and propelled new socialist categories of culture, such as folklore (minsu 民俗) and popular (minjian民间, from the ‘space’ of the people) art. New state institutions were created (song and dance teams), and national and regional surveys (1950s) produced an inventory of local traditions. The first phase of folklorization involved separating form from content (old melodies with new lyrics, for example), the sanitization of references to religion, and the creation of professional troupes. Second, the ‘reform and opening’ period (1980s onwards) saw the expansion of State institutions devoted to performing arts and folklore, the production of a new scholarship and a new wave of inventory classification, as well as, for ethic minority regions, the classification of some of their traditions in the derogatory ‘living fossil’ category (huohuashi 活化石), implying their inferiority vis-à-vis the more advanced Han culture. A second phase of folklorization involved the reintroduction of local ‘traditional’ content into performing arts genres, but extracted it from its cultural and social context, and refashioned with a standardized ‘ethnic’ (minzu 民族) flavour elaborated in conservatories in big cities on the East coast. Furthermore, traditions needed to be ‘improved’ (an idea and set of practices stemming from the USSR), for example by shortening the show and setting it on a proscenium, and by reinforcing training in conservatories (including ballet dancing, bel canto singing, and recorded music). This period also saw the branching off of performers into either State or amateur troupes (continuing their practice with no financial support from the State and keeping a somewhat more ‘traditional’ aspect to their performances).

The third period saw the accelerated economic development and mass tourism (mid 1990s onwards), which is also the period of the “Disempowered development of Tibet” (Fischer 2012, 2015). This led to a commodification of culture and a disempowerment of Tibetans’ in representing themselves in their own terms. There was a further removal of artistic forms from their cultural and social context: the Tibetan aesthetics in State troupes becoming very superficial and blended with recognizable overall ‘ethnic’ (minzu) characteristics (costumes, type of singing, music). This was also the period of the first attempts at performing style hybridization (in State troupes only), for example mixing Tibetan and Chinese operatic styles. Unsupported amateur troupes started to feel an economic pressure to adopt the State troupes’ style to become more popular and profitable.

A fourth period saw the emergence of the ICH programmes (from 2005 onwards), which will be described more in depth in the following section. I will just close this historical review here by mentioning what I see as a fifth period in cultural management in Tibet, that of the cultural securitization initiated by Xi Jinping since his ascent to power in 2012. He has personally paid a lot of attention to the performing arts and, for his ‘Revitalize Chinese cultural confidence’ campaign (2016), he decided to allot astronomical budgets for ‘culture’. Combined with new infrastructural undertakings and new technologies, this is the period of the construction of major ‘all-in-one’ cultural-cum-community centres in the TAR, which serve, at once, as exhibition halls, rehearsing and performing venues, training centres for non-professionals, and hotspots for local economic production. In addition, this fifth period features an increased hybridization of performing styles with Chinese performing traditions, including among amateur troupes (see Henrion-Dourcy, 2019).

I shall remain focused in this paper on the implementation of ICH programmes and summarize a few general observations I have made on their effects in Tibet proper (especially in the TAR). A layer of complication, when it comes to implementation, emerges from the challenges proposed by a longstanding official motto to foster ‘cultural preservation’ (wenhua baocun文化保存, translated into Tibetan as rigne sungkyob), which has become increasingly popular in Tibetan society during that period (especially after 2008) and has since given rise to numerous private local endeavours (sometimes, small museums, including medicine or Gesar exhibition halls in monasteries), grassroots projects, and even translocal movements[xxi]. The situation on the ground is thus quite complex, with the line between government policy and local society initiatives to revitalize and preserve local traditions becoming blurred.

The most striking consequence of the official ICH programme is the huge amount of government money that has been sprinkled onto various offices and private entrepreneurs through multiple programmes. From 2005 to 2018, the government spent 300 million yuan (45 millions US$) on ICH in Tibet (TAR only), mostly coming from the central government (195 million), but also from the TAR government (80 million) and the city, prefecture and county-level governments (25 million).[xxii] For ache lhamo alone, 23 million yuan was spent, plus 2 million for equipment given to troupes and 4 million for the production of over a hundred books and dozens of DVDs. New massive infrastructures have been built, such as the Opera Art Centre and Tibetan Opera Exhibition Hall in Lhasa. Numerous exhibitions have been held, shows in Eastern China cities, academic conferences (…mostly in Beijing); work and business forums such as ‘China Tibetan culture forum’, ‘Tibetan cultural heritage day’, or ‘Primitive banquet’, and other minzu culture fairs featuring ten minutes of ache lhamo. Budget spent for the Gesar epic is less important in the TAR, but more substantial in Sichuan and Qinghai provinces, where the epic is more popular: many museums, Gesar centres and performances have been supported either by the State or private interests.

As for the State support to performers, it is allotted to either troupes or individuals along the four-tier-administrative structure of the national ICH programme.[xxiii]

- At the national-level ICH awards, there are in total 89 Tibetan awards from TAR (as of 2019), out of which 7 are for ache lhamo troupes[xxiv] and 3 for individual ache lhamo performers dubbed ‘cultural inheritors’ (chuanchengren传承人, translated into Tibetan as gyüzinpa)[xxv], each category receiving a yearly stipend that varies according to the reputation and past awards of the troupe/performer. In 2016, the basic amount was increased from 10 000 to 20 000 yuan a year, for either a troupe or an individual;

- At the regional-level ICH awards: there are in total 460 Tibetan awards from TAR, out of which 11 are for ache lhamo troupes and 27 for ache lhamo ‘cultural inheritors’, with both categories receiving a yearly stipend that increased from 5 000 to 10 000 yuan in 2016;

- At both the prefecture/municipality-level and at the county-level ICH awards: the nominations are numerous and garner a lesser yearly stipend.

Beyond figures, I will share here some comments about the effects of ICH made by some Tibetans, referring mainly to ache lhamo. I will keep these general so as to make unidentifiable those who shared this information. First, most rural performers, who are generally not educated (in formal schools), do not understand the underpinnings of the concept of ‘intangible cultural heritage’ but retain a rather positive attitude towards ICH, which they construe as bringing them material benefits (money, costumes, equipment, occasions to perform, status and value in the eyes of the State, etc.). They also recognize that ICH garners more visibility of Tibetan traditions that are disappearing fast from rapidly modernizing rural areas, after decades of marginalization and hardships. The ICH program has indeed allowed the revitalization of derelict traditions in remote parts of the countryside and has brought more awareness about ‘tradition’ among the youth. Only educated and urban stakeholders voice that the ICH programme also brings more State control into artistic practice; and that there is a lot of fluff in promised returns, but little meaningful action taken where it is needed. There seems to be an unspoken yet important hierarchy between the performers and the (urban, educated) bureaucrats managing the ICH programmes (Maags 2016, 2018, 2019), who can be either Tibetan or Chinese. Calling ICH ‘yet another tool to milk the government’, observers have voiced that ICH boils down to a competition between bureaucrats for their personal benefit, rather than a meaningful way to safeguard traditions for the benefit of the local people. Nominations, especially in the regional-level or national-level ICH categories, are scant and pit bureaucrats against one other; accusations of bribes and corruption are frequent. Some bureaucrats, especially non-local government employees, want to increase the number of prestigious ICH nominations in their jurisdiction to pad up their personal rap sheet (and hope for a job transfer closer to home) and/or attract attention and pride onto their district. Other allegations include bureaucrats diverting the money allotted by the government to distant rural troupes, these not being aware of the ICH system (the file being sent by bureaucrats in their name) and ignoring the fact that they are entitled to receiving a yearly stipend. Other observations include how the real economic beneficiaries of the ICH boom are private media companies (often young tech-savvy Chinese flying in from the Eastern coastal regions), paid a lump sum of money to shoot promotional clips, or long documentaries about traditions they do not know much about, nor care to understand in depth, reduplicating stereotypes provoking disappointment for the local Tibetans involved.

Let us now move to consider the structural consequences of the ICH programme. The first one hints at the new hierarchy that has emerged between nominated and un-nominated performing traditions (such as small-scale community rituals or very local lesser known performing styles). Only ICH-labelled traditions receive economic support and are offered occasions to play, which leads unlabelled traditions to die out more quickly.

Secondly, ICH does indeed enhance visibility, give opportunities to perform (for example at State-run festivals) and sustain, to some degree, the continuous practice of art traditions; but troupes are often limited to performing a short vignette of their style (20 minutes or less). When preparing their troupes for such snippets, troupe directors confess a frustration at not being able to pass down a full tradition to the next generation. A majority of these rarefied translocal art traditions require an immersion into a whole system of knowledge and cultural references to be understood and appreciated, but only a series of ‘postcard-like’ excerpts are allowed to be ‘displayed’ for public consumption and entertainment (and approval). Therefore, in the long term, the ICH programme falls short of its core objective of safeguarding and cultural transmission, and unless careful interventions are negotiated, often manage to do little more than pass on simplified and stereotyped images. Third, the lucrative aspects of the ICH programme have provoked stark interpersonal conflicts between performers, now brought into competition with one other over money, recognition and ‘outstanding-ness’. Interestingly, the strife experienced by some tends to be expressed as bitterness over varied claims of ‘authenticity’, which is often not considered important in the Chinese ICH system: in their eyes, the ‘authentic’ lineage holders of a tradition should be awarded more money and recognition than talented newcomers to the style (also see Zhu 2015, 2019). It is a sad evolution, as the world of ache lhamo performers was until recently a tight community filled with a remarkable degree of solidarity.

Conclusion

I hope that this cursory presentation on ICH or ‘intangible cultural heritage’ will help Tibetan readers gain a better grasp of the genealogy and meaning of the concept and, most importantly, its implications. It is critical that ICH does not remain a conceptual blind spot. On the global stage, ICH is an exercise in public relations. International identity politics are now done through ‘spectacle’, and the representation of one’s nation through simplistic reified images. The crucial aspect of UNESCO’s conception of culture is that these cultural expressions are a ‘property’, an entity that is owned and managed by a State presenting itself as the legitimate custodian of that heritage.

At the level of the PRC, ICH is a crucial notion in understanding the current predicament of Tibetan culture. While definitely allowing for more visibility of folk traditions in the public and media spaces, generating more income, and offering some possibilities to safeguard and sustain cultural traditions, its actual implementation is typically fraught with complications. ICH programmes have reinforced both ancient and new hierarchies of knowledge, power and money and fostered an ever-pervasive State interventionism into the management of folk culture. The staggering budget poured into traditional culture brings about radical transformations in the name of preservation, and economic marginalization in the name of empowering local communities. But many artists and observers in the performing arts try to stake their claim to these choreographed cultural forms and, at the same time, manoeuvre within the system to try and salvage their traditions in between the dotted lines defined by their duties. I will leave the last word to one of these Tibetan cultural custodians, who perceptively remarked:

The government wears the clothes of ‘culture’ to do politics.

We Tibetans wear the clothes of ‘politics’ (obedience, loyalty) to do culture.

Transliteration of the Tibetan terms

Drametse ngacham dGra-med-rtse rnga-’cham

Khangchendzonga Gangs-can mdzod-lnga

gyüzinpa rgyud-’dzin-pa

lhakar lhag dkar

lum lums

ngöme rigne shülshag dngos (sometimes mngon)-med rig-gnas shul-bzhag

phake tsangma pha-skad gtsang-ma

rigne rig-gnas

rigne sungkyob rig-gnas srung-skyobs

Re(b)gong Reb-gong

Senggeshong Seng-ge gshong

sowa rigpa gso-ba rig-pa

tsechu tshes bcu

Chinese terms in pinyin and characters

chuancheng ren 传承人

feiwu (zhi) wenhua yichan 废物 (质)文化遗产

shaoshu minzu 少数民族

wenhua baocun 文化保存

Bibliographic References

Jo-sras-ma bKra-shis tshe-ring, 2019, “rGyal-spyi’i Bod kyi zlos-gar sgyu-rtsal zhib-’jug bgro-gleng tshogs-chen thengs dang-po dang stabs-bstun bzhugs-sgar Bod kyi zlos-gar tshogs-pa ngo-sprod mdor-bsdus dang ’brel-ba’i re-’dun zhu ’bod-tshigs gsum”, in Programme, 1st International Conference of Tibetan Performing Arts, Dharamsala, October 28-30, 2019, pp. 5-15.

Andris Silke and Florence Graezer-Bideau, 2014, “Challenging the notion of heritage?”, in Tsantsa, Vol. 19, pp. 8-18.

Arizpe Lourdes (ed.), 2013, Anthropological Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage. London: Springer.

Ashworth, G.J. 1994, “From History to Heritage – From Heritage to Identity”, in G.J. Ashworth and P.J. Larkham (eds.), Building a New Heritage. London: Routledge, pp. 13-30.

Blaikie Calum, 2016, “Positioning Sowa Rigpa in India Coalition and antagonism in the quest for recognition”, Medicine Anthropology Theory, Vol. 3 no. 2, pp. 50-86.

Blumenfield Tami & Helen Silverman, 2013, Cultural heritage politics in China. New York, Springer.

Bodolec Caroline, 2014, “Être une grande nation culturelle : Les enjeux du patrimoine culturel immatériel pour la Chine”, in Tsantsa, Vol. 19, pp. 19-30.

Bronner Simon J., 1998, Following Tradition: Folklore in the Discourse of American Culture. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Brosius Christiane & Polit Karin M., 2011, Ritual, Heritage and Identity: The Politics of Culture and performance in a globalised world. London: Routledge.

Brumann, Christoph, 2014, “Heritage agnosticism: A third path for the study of cultural heritage”, Social Anthropology, 22 (2), pp. 173-188.

Coleman Donagh and Lharigtso, 2014, A Gesar Bard’s Tale. Documentary movie, 82 minutes.

D’Evelyn Charlotte, 2018, “Grasping Intangible Heritage and Reimagining Inner Mongolia: Folk-Artist Albums and a New Logic for Musical Representation in China”, Journal of Folklore Research, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 21-48.

Debord Guy, 1970, The Society of the Spectacle. Detroit: Black and Red Books.

Denton, Kirk A., 2005, “Museums, memorial sites and exhibitionary culture in the People’s Republic of China”., in The China Quarterly, Vol. 183, pp. 565–586.

Denton, Kirk A., 2014, Exhibiting the Past: Historical Memory and the Politics of Museums in Postsocialist China. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press.

Fischer Andrew 2012, The Disempowered Development of Tibet in China: A Study in the Economics of Marginalization. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Gauthard Nathalie, 2011, “L’épopée tibétaine de Gesar de Gling. Adaptations, patrimonialisation et mondialisation”, Cahiers d’Ethnomusicologie, n° 24, pp. 171-187.

Gerke Barbara and Sienna Craig, 2016, “Naming and forgetting. Sowa Rigpa and the territory of Asian medical systems”, Medicine Anthropology Theory, Vol. 3 no. 2, pp. 87-122.

Hafstein Valdimar, 2007, “Claiming culture: Intangible Heritage Inc., Folklore©, Traditional Knowledge ™”, in Regina Bendix, Carola Lipp, and Brigitta Schmidt-Lauber (eds.), Prädikat HERITAGE. Münster: Wertschöpfungen aus kulturellen Ressourcen. Studien zur Kulturanthropologie / Europäischen Ethnologie, pp. 75-100.

Hafstein Valdimar, 2018, “Intangible Heritage as a Festival; or, Folklorization Revisited”, in Journal of American Folklore, 131 (520), pp. 127-149.

Harris Clare, 2012, The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harrison Rodney, ed., 2010, Understanding the politics of heritage. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Henrion-Dourcy Isabelle, 2016, “Heritage in bondage: On the (exc)use of ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’ in Tibet”, Presentation, Meeting of the ACHS (Association of Critical Heritage Studies), UQAM, Montreal.

Henrion-Dourcy Isabelle (ed.), 2017, Studies in the Tibetan performing Arts. Special issue, Revue d’Études Tibétaines, Vol. 40.

Henrion-Dourcy Isabelle, 2019, “Quelques voies de renouveau pour le théâtre traditionnel tibétain depuis les années 2000”, L’Ethnographie, Vol. 1, Special Issue « Renouveau et revitalisation des arts scéniques asiatiques : Discours, pratiques et savoir-faire » (ed. Nathalie Gauthard). Online:

https://revues.mshparisnord.fr/ethnographie/index.php?id=79

Hevia James, 2001, “World Heritage, National Culture, and the Restoration of Chengde”, in Positions: East Asia cultures critique, Volume 9, Number 1, pp. 219-243.

Hobsbawm Eric and Terrence Ranger (eds.), 1983, The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Barbara, 2004, “Intangible Heritage as Metacultural Production”, Museum International, 56 (1-2), pp. 52-65.

Kurin Richard, 2004, “Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in the 2003 UNESCO Convention: a critical appraisal”. Museum International, 56 (1–2), pp. 66-77.

Logan William, 2002. “Globalizing Heritage: World Heritage as a Manifestation of Modernism and the Challenge from the Periphery” in David Jones (ed.), 20th Century Heritage: Our Recent Cultural Legacy. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide, Australia, pp. 51-57.

Maags Christina, 2016, “Replicating Elite Dominance in Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding: The Role of Local Government–Scholar Networks in China”, in International Journal of Cultural Property, Vol. 23, pp. 71-97.

Maags Christina, 2018, “Creating a Race to the Top: Hierarchies and Competition within the Chinese ICH Transmitters System”, in Christina Maags and Marina Svensson, eds., 2018, Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 121-143.

Maags Christina, 2019, “Struggles of recognition: adverse effects of China’s living human treasures program”, in International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25 (8), pp. 780-795.

Maags Christina, 2020, “Disseminating the policy narrative of ‘Heritage under threat’ in China”, in International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26 (3), pp. 273-290.

Maags Christina and Marina Svensson, eds., 2018, Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Mountcastle Amy, 2010, “Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage and the inevitability of loss: A Tibetan example”, Studia Etnologica Croatica, 22 (1), pp. 339-359.

Oakes Tim, 2012, “Heritage as Improvement: Cultural Display and Contested Governance in Rural China”, in Modern China, Vol. 39-4, pp. 380-407.

Rees Helen, 2012, “Intangible cultural heritage in China today: Policy and practice in the early 21st C.”, in K. Howard (ed.), Music as Intangible Cultural Heritage: Policy, Ideology, and Practice in the preservation of East Asian traditions. London: Routledge.

Rees Helen, 2018, “Intangible cultural heritage in contemporary China: the participation of local communities”, in International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24 (5), pp. 570-572.

Sangye Dondhup, 2017, “Looking Back at Tibetan Performing Arts Research by Tibetans in the People’s Republic of China: Advocating for an Anthropological Approach”, in Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, vol. 40, pp. 103-125.

Saxer Martin, 2012, “The Moral Economy of Cultural Identity: Tibet, Cultural Survival, and the Safeguarding of Cultural Heritage”, in Civilisations (61-1), pp. 65-81.

Schrempf Mona, 2016, “Tibetan medicine / Sowa Rigpa as intangible cultural heritage –issues and developments”, Unpublished presentation made at the 14th IATS Seminar, Bergen (Norway), 22 June 2016. The powerpoint presentation is accessible on Mona Schrempf’s Academia page: https://www.academia.edu/28306347/Tibetan_Medicine_%E0%BD%82%E0%BD%A6%E0%BD%BC_%E0%BD%96_%E0%BD%A2%E0%BD%B2_%E0%BD%82_%E0%BD%94_and_Chinas_Intangible_Cultural_Heritage_Issues_and_Developments

Schrempf Mona, 2017, “Tibetan Medicine-Sowa Rigpa as Intangible Cultural Heritage – Latest news from India and China”, Blog of the European Association for Traditional Tibetan Medicine- EVTTM Yuthok, https://tibet-medicine.org/pages/topics/tibetan-medicine.php?lang=EN

Shepherd Robert, 2006. “UNESCO and the politics of cultural heritage in Tibet”, in Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 36 n° 2, pp. 243–257.

Shepherd Robert 2009. “Cultural heritage, UNESCO, and the Chinese state”, in Heritage Management vol. 2 n°1, pp. 55–80.

Shepherd Robert 2014, “Civilization-Making and Its Discontents: The Venice Charter and Heritage Policies in Contemporary China”, in Change Over Time, 4 (2), pp. 388-403.

Shepherd Robert, 2017, “UNESCO’s Tangled Web of Preservation: Community, Heritage and Development in China, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47 (4), pp. 557-574.

Shepherd Robert & Larry Yu. 2013. Heritage Management, Tourism and Governance in China: Managing the Past to Serve the Present. New York and London: Springer Press.

Smith Laurajane, 2006, Uses of heritage. New York: Routledge.

Smith Laurajane and Natsuko Akagawa (eds), 2009. Intangible Heritage. London: Routledge.

Smith Laurajane and Natsuko Akagawa (eds), 2019. Safeguarding Intangible Heritage: Practices and Politics. London: Routledge.

Thomason Alison K., 2005, Luxury and legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia. Hampshire: Ashgate.

Thurston Timothy, 2019-a, “The Tibetan Gesar Epic Beyond its Bards: An Ecosystem of Genres on the Roof of the World”. Journal of American Folklore, 132 (524), pp. 115-136.

Thurston Tim, 2019-b, “Heritage with and without the State: Observations on the Gesar Epic in Yushu”, presentation in Chris Berry, Anup Grewal (conveners), “Understanding the Tibetan Cultural Renaissance Inside the PRC”, Workshop, U. Toronto, April 2019.

Wojahn Daniel, 2016, “Preservation and Continuity: The Ache Lhamo Tradition Inside and Outside the Tibet Autonomous Region”, Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, 37, pp. 534–550.

Yan Haiming, 2016, “World Heritage and National Hegemony: The Discursive Formation of Chinese Political Authority”, in William Logan, Mairead Nic Craith and Ullrich Kockel (eds.), A Companion to Heritage Studies. London: Blackwell, pp.229-242.

Yan Haiming, 2018. World heritage craze in China: Universal discourse, national culture, and local memory. Oxford: Berghahn.

Zan Luca & S. Bonini Baraldi, 2012, “Managing Cultural Heritage in China: A View from the Outside”, in The China Quarterly, Vol. 210, pp. 456-481.

Zhu Yujie, 2015, “Cultural Effects of Authenticity: Contested Heritage Practices in China”, in International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 17, pp. 1-15.

Zhu Yujie, 2019, “Politics of scale: Cultural heritage in China”, in Tuuli Lähdesmäki , Suzie Thomas and Yujie Zhu (eds.), Politics of scale: New directions in critical heritage studies. Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 21-35.

Zhu Yujie & Christina Maags, 2020, Heritage Politics in China: The Power of the Past. London: Routledge.

Acknowledgement: This article was written in 2019, in the wake of TIPA’s 60th Anniversary conference, in Dharamsala. It was planned to be published in the conference proceedings, edited by Josayma Tashi Tsering and titled: Mig yid rna ba’i dga’ ston, A Feast for the Mind and the Senses. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Tibetan Performing Arts, October 2019. Due to Covid-19 restrictions between 2020-2021, and other unavoidable obstacles, there have been delays in the production of the four hefty volumes of these multilingual proceedings. They are well worth the wait, as this collection is set to become a classic reference on the topic, especially for the rich original materials brought forth in the articles in Tibetan or written by Tibetan scholars. Given the delay in production, the editor Josayma Tashi Tsering has given permission for the authors to publish their works in other outlets before the proceedings finally come out. Warm thanks are owed to him, since this text was fed by his input and numerous conversations we have had over the years. Finally, my gratitude goes to Colin Millard and Jeffrey Cupchik for their help in improving my idiosyncratic English, and to the anonymous reviewer for insightful constructive criticism.

[i] Actually, Tashi Tsering, the Director of Amnye Machen Institute, has tried on a number of occasions since 2003 to bring some awareness to exile Tibetans about the concept of ICH and its political implications, especially in the realm of performing arts. For example, during the first ever meeting of the Tibetan ache lhamo Association (Bod kyi a-lce lha-mo’i ’gan-’dzin lhan-shogs) held at TIPA in 2006, he mentioned the PRC’s moves to have ache lhamo recognised as an ‘ICH of China’ at UNESCO. He reiterated comments to the director of the TIPA on the need to make a public statement after China’s winning the proclamation in 2009. But his remarks never met with concern or attention (see Jo-sras bKra-shis tshe-ring, 2019, pp. 9-10).

[ii] I thank Mona Schrempf (personal communications 2019-20; see also Schrempf 2016 and 2017), for her useful comments and explanations, as she has done extensive research on the nomination of Tibetan Traditional Medicine as deserving of ICH status. All potential misunderstandings are my own. This is a vexed issue and there are several layers of complexity to be considered. The first issue rests in the tension between exile Tibetan physicians and physicians practising the same medical system in the Northern Himalayan borderland fringes of India, for example in Ladakh (see Blaikie 2016). The latter do not identify as ‘Tibetans’, so they use the term sowa rigpa, not ‘Tibetan traditional medicine’ (TTM), to describe their medical system, for example in their dealing with the Indian administration for traditional medicines, i.e. the ministry of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga and naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy). From 2014 onwards, as the Chinese government started pushing to have TTM inscribed as their own treasure on the UNESCO’s ICH representative list, the Indian government reacted by seeking to protect what it considered the legitimate heritage of its own people, seeing TTM as an extension of the Ayurvedic Medicine system. Yet the exile Tibetans initially did not want to be involved. At around this time, a Western anthropologist went to meet the director of the Tibetan Medical & Astro-science Institute (TMAI) in Dharamshala to give explanations about ICH and China’s intentions and suggested a joint multinational file application (India and China) for sowa rigpa at large to support its global recognition. It resulted in a quiet indifference. It was followed by a talk in front of the director of the Institute, the principal of the Tibetan Medical & Astro. Science College, teachers, students, and senior physicians in the Dharamshala area. On that occasion again, the presentation did not meet with concern. In another layer of complexity, it seems that the very term ‘intangible’ in ICH is rejected by exile Tibetans, maybe imagining in this term connotations of ethereality, or lack of seriousness. The quick rejection of the term ‘intangible’ can be seen in the following excerpt of a 2017 article in Phayul: “Tsering Phuntsok, the Registrar of the TMAI who has been with the organization for over 25 years, says the Tibetan traditional medicine is on the upswing and putting it in the same bracket as Qawwali, Nautanki, Kalamkari paintings, Durga Puja and listing it as an intangible entity is a no-brainer. “The Tibetan Sowa Rigpa tradition is a science, no less a science that has healed and continues to heal countless chronic and sometimes terminal patients over the years, how is it intangible? We’ve had discussions earlier as well and the Director has made it abundantly clear that categorizing Tibetan medicine as intangible will never be accepted by the Institute,” Phuntsok told Phayul”. In: Tenzin Dharpo, 2017, “Tibetan medicine nomination in UNESCO’s ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage List’ unacceptable: Senior TMAI official”, Phayul, 13 April 2017. http://www.phayul.com/2017/04/13/38921/ (last accessed 1 October 2020). Emphasis added.

[iii] Sowa rigpa is the Tibetan term designating medicine, literally, the ‘science of healing’. However, opting for this term in the application, instead of the standard English denomination of ‘Traditional Tibetan medicine’ (TTM), infuriated several Tibetan exiles, who felt this choice of words erased the ethnic group that produced this system of knowledge. But it is how Ladakhis and other ‘non-Tibetan’ physicians in the Himalayan regions of India designate their medical system. It is remarkable that both the Indian and Chinese governments, who carried the application, chose the same denomination in the Tibetan language.

[iv] On the nationalistic politics surrounding sowa rigpa, see Gerke & Craig (2016).

[v] As most exile Tibetans live (or were born and raised) in South Asia or in countries fashioned by the British empire (India, USA, Australia, New Zealand, and of course the UK), the Anglo-Saxon culture and the English language have decisively shaped how Tibetans not only think of themselves collectively and articulate their struggle, but also construe ‘the West’ (a reductionist word that is of course meaningless).