ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

“Instashrine” as Heterotopic Space

in Gonkar Gyatso’s Buddha’s Picnic

Melissa Kerin

Abstract: Unlike any of his previous work, contemporary artist Gonkar Gyatso, creates a fully immersive and haptic experience through his installation, Buddha’s Picnic, a space in which shrines, picnics, Mahjong, and beer irreverently collide. The focus of the installation is a small and brightly decorated shrine-like construction that Gyatso places on a diagonal axis along a 25 x 28 foot expanse of green plastic turf laid out over the majority of the gallery space. Lights blink and layers of sound spill from the brilliantly collaged shrine-like structure constructed from mass-produced and electronic devotional objects. Gyatso explains: “I’m interested in exploring this idea of the instant, how everything has to be made and displayed quickly, like Instagram. Here is Instashrine.” By positioning Instashrine as the center piece of this interactive installation, Gyatso provocatively juxtaposes time periods, traditions, locations, and sounds to interrogate preconceptions about Tibet, Tibetans, and Buddhist practice, as well as to highlight complex social relations and historical moments related to life in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. The space Gyatso creates is akin to what Foucault would call a heterotopia, a space that exists outside conventional sites and rules, and effectively refracts, inverts, and even destabilizes normative principles and spaces. Gyatso invites his viewers into this space, to eat, lounge, play, and to consider the nested set of complex socio-political concerns and identity questions pulsing from the Instashrine and thrumming throughout the whole installation.

Keywords: altars, collage, heterotopia, readymade, shrines

Though his face was slightly pixilated from the poor Skype connection between Lexington, VA, in the U.S. and Chengdu, China, it was clear that contemporary Tibetan artist, Gonkar Gyatso, was searching to explain his then very strained relationship to shrines. “The more I try to figure out the shrine, the more I feel outside. I don’t really practice Buddhism, I don’t have a specific lineage. I feel an outsider, emotionally disconnected from the shrine. When I was working on the Buddha’s form I felt in love with it: the form, the colors. But this is different.”[1]

Indeed, this installation project, Buddha’s Picnic (2018),[2] was quite different from anything Gyatso had constructed before. Much of his earlier work relied on the rigid structure provided by the iconometric measurements of the Buddha.[3] In these two-dimensional works he combined pop art and kitsch with precisely rendered forms of Buddhas scored by measurement lines (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Buddha in Our Time, 2008, 155×122 cm mixed media collage on fine paper, courtesy of the artist

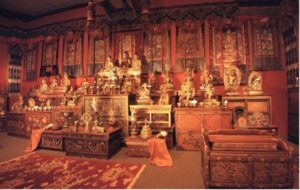

On one level, Gyatso depicts the silhouette of the Buddha, but within that he creates endless minutia of juxtaposed images and pairings. The structure and two-dimensionality of these iconometric images contrast with the endlessly idiosyncratic and flexible forms of shrine assemblages that simultaneously attracted and stymied Gyatso. Moreover, he began to associate the shrine with the large, immoveable, imposing spaces found at Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and even Western museums where a certain shrine type has become common within displays of Tibetan art (fig 2-3).[4] Eventually, however, Gyatso experienced a critical shift in his ideas about shrines after seeing a photograph of a shrine in a Tibetan nomadic context. In a telephone conversation, Gyatso said “I saw a photo of nomads bringing the altar outside, I thought, that would be the perfect setting.”[5]

Figure 2: Main shrine at Pelkor Chode Monastery, Gyantse (Tibetan Autonomous Region), photo by Melissa Kerin

Figure 3: “Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room” from the Alice S. Kandell Collection as presented at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, photo by Melissa Kerin

Seeing shrines of nomadic communities opened for Gyatso a new conceptual arena. He combined open grasslands and decadent picnics with a small-scale, mobile shrine onto which he layered his playful, collaged aesthetic. This ultimately yielded Buddha’s Picnic, an installation that premiered at Washington and Lee University’s Staniar Gallery in February 2018 (fig. 4). The focus of the installation was a small and brightly decorated shrine-like construction that Gyatso placed on a diagonal axis along a 25 x 28 foot expanse of green plastic turf laid out over the majority of the gallery space. Blinking lights and layers of dissonant sound spilled from the brilliantly collaged shrine-like structure assembled from mass-produced and electronic devotional objects (fig. 5). He explained: “I’m interested in exploring this idea of the instant, how everything has to be made and displayed quickly, like Instagram. Here is Instashrine.”[6] By positioning Instashrine as the center piece of this interactive installation, Gyatso provocatively juxtaposed time periods, traditions, locations, and sounds to interrogate preconceptions about Tibet, Tibetans, and Buddhist practice, as well as to highlight complex social relations and historical moments related to life in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. I suggest that the space Gyatso created is akin to what Michel Foucault would call a heterotopia, a space that exists outside conventional sites and rules, and effectively refracts, inverts, and even destabilizes normative principles and spaces. Gyatso invited his viewers into this space, to eat, lounge, play, and to consider the nested set of complex socio-political concerns and identity questions pulsing from the Instashrine and thrumming throughout the whole installation.

Figure 4: Buddha’s Picnic Multimedia installation by Gonkar Gyatso, photo by Kevin Remington

Figure 5: Detail of Buddha’s Picnic

The paper is organized around four interrelated topics. The first explicates the artist’s conception and organization of the fully immersive installation. I then focus on Instashrine at the center of Gyatso’s installation and frame it within the concept of Foucault’s heterotopia. After unpacking the meaning of the shrine’s visual vocabulary, I place Gyatso’s Instashrine within the larger scope of his artistic milieu to show how his concept and image of shrines have evolved over the last 15 years.

Buddha’s Picnic: Conception and Organization

In Gyatso’s first sketches he aligned the outside, nomadic world with the concept of picnicking, a much loved activity among most Tibetans no matter their standing or occupation (figs 6-7). A picnic in Tibetan is commonly referred to as linga (Tib. gling ga), which also carries the meaning of garden or park. The word thukdro (Tib. thugs spro) is frequently used as well, though this conveys the double meaning of banquet and happiness. Thus, picnicking and feasting are symbols par excellence of relaxation and abundance within the Tibetan cultural context: representing a space where people have time to play games, drink, talk, and eat. By bringing the shrine into the social environment of the picnic, Gyatso effectively removed it from its expected sanctified environs of monastery and museum. He said that without the picnic, the shrine itself as a topic for the installation was too severe. “The picnic makes it a more welcoming feeling for the shrine.”[7] And indeed the welcoming feeling is enhanced by the way Gyatso invites the viewer into the space with cushions and trays overflowing with snacks.

Figure 6: Sketch of Buddha’s Picnic by Gonkar Gyatso, 2017, photo by Melissa Kerin

Figure 7: Sketch of Buddha’s Picnic by Gonkar Gyatso, 2017, photo by Melissa Kerin

It was not until Gyatso arrived in Lexington, Virginia that he fully conceptualized the installation’s layout. Walking through the gallery space as the green plastic grass was being rolled out, Gyatso immediately decided that the focal point of the installation, the Instashrine protected by an open umbrella, would be in a corner of the room, hidden from immediate view (fig. 8). He wanted it to be a surprise for viewers who, from the gallery’s glass doors, could only see an expanse of green grass and perhaps hear a hint of the music emanating from the not-yet-seen shrine.[8] Inside the installation, the tall, 6-foot umbrella, with a wide canopy of yellow and green, commands the space. Under it sits the readymade altar measuring roughly 30 inches tall. This area comprises the first of three interactive zones.

Figure 8: Gonkar Gyatso installing Buddha’s Picnic, february 2018, photo by Melissa Kerin

The second zone lies just outside this protected altar area. Gyatso placed two brightly colored, traditional Tibetan carpets opposite one another. Strewn on these are cushions covered with synthetic material decorated with bold and whimsical designs of fruit and doughnuts. The food theme continues with heaps of packaged Chinese snacks and biscuits, candy and dried meats piled onto six red trays painted with floral patterns. Canned and bottled beverages neatly surround these assemblages of food. Gyatso organized this picnic area with systematic precision, carefully measuring and placing carpets, cushions, trays, foil-wrapped food stuff, and bottles of drinks until he created a powerful composition straddling intended symmetry and carefree happenstance (fig. 9). Connected to this picnic area, but constituting its own zone by virtue of its placement, elevation, and lighting, is the game area, with a bright green Mahjong game board and pink plastic game pieces scattered atop the surface. Unlike the rugs and trays placed directly on the ground, Gyatso perched the game board on brown cardboard boxes. Placed around the Mahjong board are pastel-colored plastic stools decorated with decals of bears and puppies inviting the gallery-goer to sit and play (see fig. 4).

Figure 9: Buddha’s Picnic detail: Trays full of snacks and drinks, photo by Kevin Remington

All three zones work together to create a wholly immersive environment, inviting gallery visitors to come in from the edges, take off their shoes, and walk through the installation with grass under foot, and to lie on the carpets, eat snacks, and play Mahjong. Gyatso does not offer, however, any single message or interpretative frame for the whole experience. Rather, visitors are meant to interact with these zones on their own, and in so doing, they come away with endlessly divergent interpretations and experiences. For instance, visitors started to leave offerings on the altar, such as lipstick, a safety pin, buttons, and a flower, among many other objects. That visitors left traces of their presence at the installation reminds one of the very lived quality of actual shrines as organic and interactive sites where people give offerings and make physical contact with the shrine itself.[9] Though the Instashrine functioned quite similarly to a real shrine for some gallery visitors, it is important to stress that Buddha’s Picnic does not contain an authentic, consecrated shrine space. Rather, it is an invented and superficial space full of plastic and carefully constructed collaging, along with sonic layering, which initially seduces the visitor with its disarming playfulness. After visitors are relaxed and sated, there are deeper levels of engagement awaiting anyone willing to think past the allure of a colorful playground-like environment. Embedded throughout the installation are moments of dissonance, audible and visual, that allude to layers of socio-religious paradoxes and complexities. I refer to this mash-up as a purposeful creation of a heterotopic space, one that pushes against utopian images and consequently brings together many locations, realities, and time frames into one space.

Heterotopia of Instashrine and Its Surrounds

While heterotopia was not a concept Gyatso used when creating his installation, it is a useful frame for analyzing and interpreting the artist’s dense and layered assemblage, which compresses and challenges time and location, and is full of contradiction and inversion.

Foucault’s initial thoughts about heterotopic spaces, a term he coined and first defined in his 1966 book The Order of Things, were more of a starting point than a closed definition of heterotopic spaces. Foucault first uses the metaphor of language to express his ideas of heterotopia’s power to undermine and invert syntax–taken broadly as normative structures. Foucault explains how heterotopias do not fit in “ordinary cultural spaces”[10] and yet they still respond to and reflect conventional realities. Later, in 1967, Foucault’s lecture “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” further elucidates the idea of heterotopias and outlines six different principles by which they can be described and assigned meaning, providing a useful outline for thinking about spaces or experiences that could be understood as heterotopic.[11]

Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias.[12]

Scholars of various disciplines have since worked and reworked this very malleable concept as it can relate to a wide spectrum of spaces and human engagement within. In essence, the concept has lived well beyond Foucault’s initial and rather short-lived discussion of heterotopia.

Foucault explains that heterotopias are “something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted.”[13] Indeed, Gyatso’s installation creates such a counter-site laden with images and sounds—religious, commercial, political, celebrity. In so doing, Gyatso creates visual and audible adjacencies that point to fraught histories and speak to complex relationships between Tibet and other cultures, such as India, China, and countries in the West. But his visuals also undeniably suggest a cheeky irreverence that creates both comic relief and destabilizing uncertainty for the viewer. For instance, Gyatso pulls together the sacred spaces of mandalas and shrines with the secular amusements of Mahjong and picnics in ways that are not only playful and humorous, but confounding and troubling.

The following is a full analysis of the Instashrine and its surroundings, giving special attention to the iconography of the piece, and how the visual vocabulary and its placement intentionally create micro-relationships and mash-ups. At various points of this analysis I return to the ways in which heterotopia is a productive and appropriate concept for thinking about this piece as it compresses, upends, and resists normative spaces of and separations between sacred and secular, Buddhist and political, quotidian and celebrity.

Under an Umbrella

The viewer first notices a poignant pairing of symbols under the umbrella protecting the Instashrine. Strings of small flags hang from the ribs of the open umbrella. Some feature the national flag of the People’s Republic of China, a red flag with a large gold star in the upper left corner with four smaller stars around it in a semicircle (fig. 10). It is a potent and clear symbol of communist China.[14] The other strings of flags are colorful Tibetan prayer flags with Tibetan prayers printed on them. One flag is political, the other religious; one a symbol of expansion into and occupation of Tibet and the other an emblem of ongoing devotional practice among Tibetans.

Figure 10: Gonkar Gyatso assembling Instashrine (note flags under the umbrella), photo by Kevin Remington

While these flags represent two different realities, it is not uncommon to see them flying together. For instance, one might see these flags in proximity to one another in a city like Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. Nearly every store, monastery, and nunnery in Lhasa hangs the red PRC flag.[15] On the rooftops of these same buildings, one will often find prayer flags flying high. By pairing these symbols, Gyatso captures the binaries one would encounter in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. But one needs to be aware that there is yet a third signifier: the umbrella itself. It is an emblem of protection throughout Asian cultures, but this specific umbrella advertises a daycare in Chengdu, China. So, in this part of the installation, which protects the altar below, Gyatso brings together commercial, political, and devotional worlds from different geographic locations. This multi-locality and multi-valency, themes I will address later in the paper, contribute to creating the overall heterotopic space of this installation.

What is easily overlooked is the upside-down cardboard box on which the Instashrine is placed. From a Tibetan cultural perspective, sacred objects need to be elevated off of the ground. This is true for any sacred object whether it is an image, altar, sculpture, or religious manuscript. To place such an object on the ground would be a sign of disrespect. In this case, the box serves the much-needed purpose of elevating the shrine, but not without some irony. Imprinted on the box in both Chinese and Tibetan is the name of a specific brand of beer (fig. 11). Gyatso’s choice to place the altar on a box of beer is not only a bit humorous, but it is also practical. At a typical picnic there would be beer drinking, and it would make perfect sense to reuse this sturdy, cardboard box as the platform for the altar. With this gesture Gyatso creates a jarring pairing between secular and sacred, and also nods to the importance of the inventive repurposing of everyday objects.

Figure 11: Buddha’s Picnic detail: Gonkar arranging Instashrine (note altar on beer box), photo by Kevin Remington

Exterior of Altar

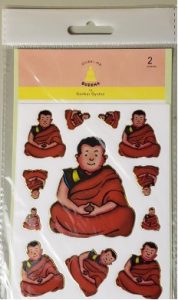

The surface of the lacquered wooden altar, which serves as the frame for Gyatso’s Instashrine creation, is covered with a pastiche of imagery that reflects secular, commercial, sacred, and political themes as well as the multi-locality also seen with the umbrella and its flags. On one side of the altar, one finds an image of the Eiffel Tower cut from a magazine and pasted atop a depiction of a Tibetan Buddhist monastery. Elsewhere, lipstick advertisements and faces of models are layered into the imagery on the outside of the altar. This collaging with magazine images, advertisements for racecars and watches, and Buddhist images of ascetics, deities, and monastics environs is the artist’s aesthetic signature, as can be seen in figure 1. Gyatso also liberally applies stickers on the veneer of this altar; these stickers feature unrelated and random images of crowns, hearts, cartoon-like animals and monks (fig. 11). It should be noted that these stickers of jovial monks sitting cross-legged in red robes are part of a production of stickers—Sticker-Me-Buddha—designed and produced by Gyatso and made in China (fig. 12). Gyatso started this line of sticker production several years ago at the suggestion of a friend, and the stickers usually depict cartoon figures of happy monks or Buddha-like figures. Stickers, as noted earlier, are a signature component of Gyatso’s two-dimensional artistic work where he uses them to create layered and intricate worlds of imagery within a single composition, and if you look carefully enough, you can find these Sticker-Me-Buddha stickers in some of his other collaged works. Within the context of his art projects, they become a reference for the artist, but also the socio-economic practice that the artist often critiques and questions: the commodification of the sacred. These stickers make a notable appearance in a 2014 work discussed below.

Figure 12: Sticker me Buddha stickers designed by and produced for Gonkar Gyatso, photo by Melissa Kerin

Moving from the exterior surfaces, I want to draw attention to the top and bottommost areas of the altar structure where there are collections of automated and mass-produced Buddhist shrine objects. At the top of the structure, we find an eye-catching pink and white plastic three-dimensional form of a white-robed androgynous figure reminiscent of Guanyin (Chinese Buddhist Bodhisattva of compassion), but whose form and iconography are rather amorphous (fig. 13). When it is turned on, a swirling light emanates from behind the robed figure and a recording of various mantras sonorously plays. A plastic grouping of three butter lamps with LED lights sits behind this automated object; in Tibetan these butter lamps are called chume (Tib. mchod me) and serve as an offering of light at a shrine or altar. To either side of the figure is a plastic lamp and a gold statue of a Buddhist figure. On the floor in front of the Instashrine is another electronic group of lamps, this one comprised of seven LED lights. In front of this grouping of electric chume, Gyatso places one real lantern made of copper, as if providing the original referent on which these plastic, made-in-China copies are derived (fig. 14). This ten-inch butter lamp is one of the few un-mechanized objects at the Instashrine, but it is nonfunctional: without butter or wick. It is impotent as a functioning object at the Instashrine as it needs human engagement and knowledge of intangible cultural heritage to activate; it requires more than plugging something into an outlet and pressing the “on” button. A wick needs to be made and properly inserted into the base of the lantern. Oil or melted butter must be poured over the wick and into the bowl of the lantern; a match struck to light the wick. Here, however, the lantern stands empty, as a portent of a time when this traditional knowledge is lost to a mechanical age. Gyatso explains:

Someone can make a complete shrine in one day now. And no one has to say even mantras or light butter lamps. It’s all done. You just plug it in. The shrine is already made…but the shrine seems lost in this mass-produced materiality.[16]

Figure 13: Buddha’s Picnic detail: Top of Instashrine, photo by Kevin Remington

Figure 14: Buddha’s Picnic detail: Butter lamp, circled at the base of the Instashrine, photo by Melissa Kerin

He compares this instant-shrine making process of today to the time he helped his grandmother create her shrine back in Lhasa in the early 1980s, a time when Deng Xiaoping’s reforms relaxed State ideology and opened toward religious practice and cultural traditions among minorities in China.[17] At this time, Gyatso’s grandmother was able not only to create a new shrine, but incorporate it into her daily practice. This shrine, explains Gyatso, was his first engagement with Tibetan Buddhist shrines, and it was a memorable one for him.[18] As he remembered during a conversation, every part of his grandmother’s shrine took time to create; the wooden altar was carved and painted, there were brass butter lamps and metal statuary. While Gyatso compares shrine making practices from two very different periods, he does not seem to get sentimental, but rather expresses his bewilderment and skepticism in equal measure.

Interior of Altar

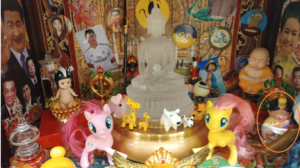

Inside the altar niche is where one finds the densest accretions of imagery and objects; there is an endless array of plastic cartoon-like animals mixed with Buddhist statuary, photographs, medallions, stickers, magazine pictures and the like. The minutia and contrasting subject matter overwhelm the eye. The central part of the niche focuses on a three-dimensional, plastic image of Shakyamuni Buddha in his Earth-Touching mudra. While figure 15 shows this sculpture looking like frosted glass, when fully activated from an application on Gyatso’s phone, the sculpture emits a bright light that changes color. Behind this is an image of a mandala, across the surface of which, the artist stuck medallions of Tibetan Buddhist lamas, portraits of Mao, and wallet-sized photos of famous soccer players, as well as images of Asian models. In front of the plastic Buddha sculpture, Gyatso placed two colorful horse figures, a Chinese version of Hasbro’s My Little Pony (fig. 16). They are, as Gyatso later explained, the gatekeepers for the shrine.

Figure 15: Buddha’s Picnic detail: Interior of altar niche (note Red Guard figure to the right), photo by Melissa Kerin

Figure 16: Close-up with the two Hasbro-like horses (Circled is the figurine of a Tibetan woman in traditional dress. She is partly obscured by the Red Guard’s gun.), photo by Melissa Kerin

While any number of objects could be discussed, here I will focus my discussion on a few poignant visual relationships Gyatso carefully creates within this assemblage. I suggest that these choreographed adjacencies tap into complex histories and intentionally highlight knotty socio-historical tensions. For instance, on the altar, Gyatso almost hides a cartoonlike plastic figurine of a Tibetan woman (seen in figure 16 to the right of the yellow pony), whose hair is made to look as if it were decorated with pieces of amber and turquoise. She wears traditional Tibetan dress with a colorful apron while offering, with both hands, a katha or ceremonial scarf. These are souvenirs of “Tibetan” people produced in China and available for purchase in Tibet, but also cities like Chengdu. Though difficult to see the small female figure inside the altar, what is clearly visible is the relationship that Gyatso constructs: the diminutive, even infant-like happy Tibetan figure stands in the shadow, quite literally, of the cheerful Red Guard member with his belted uniform featuring a red lapel and arm band and a gun jauntily slung over his right shoulder (fig. 15). In fact, in figure 16 the Tibetan woman is partially obscured by the brown hilt of the Red Guard’s gun. The Red Guard figurine is one of the largest of the whole composition. Playing with scale, Gyatso places a miniature plastic model of the Potala Palace (the winter abode of the Dalai Lamas in Lhasa) in front of the Red Guard, who towers over the model of the palace (fig. 15). But the imposing presence of the Red Guard goes beyond the physicality of the shrine and demands that we attend to the recent past of the People’s Republic of China and its relationship to Tibet. The Red Guard is symbolic of the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, a period that brought devastation throughout China, including Tibet. When one sees the Red Guard, the assumption is likely that this figure represents a young Chinese person, but in Tibet the Red Guard included Tibetans.[19] Thus, Gyatso raises complicated questions about Tibetanness and Tibetan identity in this one pairing, a line of inquiry he began investigating in his 2003 series of photographs he entitled My Identity.[20] Here, in Instashrine, Gyatso layers and pairs figures and symbols, which alone are rather innocent, but when adjacent to one another evoke a complex history of social relations. It is up to the viewer to create and question these pairings, as Gyatso does not present a single viewing experience or provide one perspective through which to understand the installation. Rather, Gyatso suggests that this assemblage, like history itself, is a messy and layered thing full of knotty intersections and unexpected connections.

Other pairings throughout the composition are equally provocative. We see Chinese political officials, but most prominent is Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China, who is positioned across from his wife, Peng Liyuan, a well-known singer in China. These Chinese officials are intermixed with images of Tibetan religious figures (fig. 16) and pop stars from all over the world. For instance, Xi Jinping’s face appears over a copy of a painting of Guru Rimpoche, a legendary and historic Indian figure strongly associated with disseminating Tantric Buddhism to Tibet and who is connected with the oldest lineage of Tibetan Buddhism (fig. 17).[21]

Figure 17: Buddha’s Picnic detail: an image of PRC President, Xi Jinping, photo by Melissa Kerin

Figure 18: Buddha’s Picnic detail: an image of Peng Liyu, Xi Jinping’s wife and well-known Chinese singer, photo by Melissa Kerin

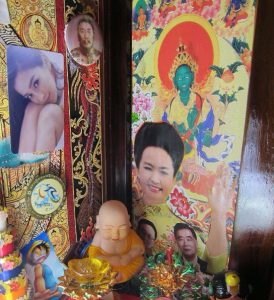

Peng Liyuan’s portrait is placed over a colorful print of Green Tara, a much beloved bodhisattva of Tibetan Buddhism who protects her devotees from fears and misfortune (fig. 18). Scattered throughout this interior space of the Instashrine are small-scale portraits of religious teachers, many in the form of round medallions or pins. Gyatso’s apposition of political and religious figures points to a common practice within modern-day Tibet. Anyone who has been to the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) sees how political posters are commonly displayed alongside religious images in both shops and within temple compounds. In poster stores in Lhasa, there is a purposeful conflation of these two worlds—political and religious—where popular posters of PRC leaders hang alongside an image of the most significant Buddhist image in all of Tibet, the Jowo in the Jokhang, the first Buddhist temple commissioned by Songtsen Gampo in the seventh century (figs. 19-20). Another example of this real-life pairing can be found at the compound of Tibet’s first monastic center, Samye. Nowadays, one will find a massive political poster placed high on the façade of one of the compound’s walls (fig. 21).

Figure 19: Shop in Lhasa (TAR) selling posters and photographs with religious and political imagery, photo by Melissa Kerin

Figure 20: Detail of political posters positioned next to a poster of the Jowo Buddha, photo by Melissa Kerin

Figure 21: Political poster and Chinese flag hanging within the compound of Samye Monastery, TAR, photo by Melissa Kerin

Thus, the microcosm that Gyatso creates in this shrine space references a much larger reality of tensions played out within contemporary environs of the TAR. By incorporating these types of images in his artistic creation, Gyatso is reflecting the reality of modern-day Tibet where religious and political images are commonly juxtaposed. Gyatso’s massing of materials reminds us of Foucault’s definition of heterotopias as “other spaces” that exist between the well accepted and defined notions of utopia and dystopia. Foucault uses the metaphor of language when discussing the power of heterotopias. He writes:

Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names, because they destroy ‘syntax’ in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things (next to and also opposite one another) to ‘hold together’.[22]

By drawing attention to this tangle of imagery, Gyatso is asking what holds these layers of meanings and objects together.

This installation contains another reminder of the political nature of Buddhist practice in the Tibetan Autonomous Region: the omission of the most well-known visage of the Tibetan world, that of the Dalai Lama. He is, in fact, part of the shrine, but hidden from immediate view. Hanging on the back of the Instashrine is a small thangka-like image replete with a traditional brocaded frame in colors of maroon, yellow, and red (fig. 22). Draped over the top of the thangka is a thin piece of yellow silk that traditionally serves as a dust covering, but here works to conceal further the Dalai Lama’s visage. Underneath the thin silk, one will find a montage of three separate images. The first is a copy of a traditional painting that would have featured a deity or teacher, except a photograph of the Dalai Lama with Reverend Desmond Tutu of South Africa is laid over the area where the main deity would be positioned. Layered over this double portrait of the friends and religious leaders is another photograph of the Dalai Lama, who looks out to the viewer with a smile. That this thangka, featuring images of the Dalai Lama, is hidden from direct view speaks to the informal restrictions in the Tibetan Autonomous Region, where owning and displaying images of the Dalai Lama is highly discouraged, sometimes even punishable. Gyatso subtly suggests that while people in the TAR may not be able to display images of the Dalai Lama freely, these types of images are there, but not easily surveyed.

Figure 22: Buddha’s Picnic. On the back of Instashrine (note the thangka draped with a thin piece of yellow silk covering the Dalai Lama’s visage), photo by Kevin Remington

Soundscape

Gyatso not only creates visual points of dissonance through powerful pairings and careful placements of images, but he also creates audible discord by crafting a layered soundscape of Tibetan songs, Buddhist chants, and Chinese pop songs, which are all played simultaneously. While the repetition and dissonance of the sounds are initially inviting and playful, one can never drift too far into this fully immersive environment. In many ways, the dissonant sounds—of songs, mantras, and religious teachings in male and female voices in both Tibetan and Chinese—prevent this installation from becoming a utopian experience of picnicking and eating snacks, a respite from the everyday pulls of life.[23] Rather, the audio collage eventually grates against the ear, jarring viewers out of any relaxed state. In doing so, Gyatso pushes viewers to grapple with the meaning of so much audio disharmony and visual anachronisms. Another example of this is the inherent contradiction of an outdoor picnic with a fully mechanized shrine that is dependent on electricity. Gyatso does not easily allow you to forget this point as he keeps visible all the cords and adaptors that are necessary for powering this shrine.

The collision and conflation of time frames, symbols, and geographies (China, Tibet, India, South Africa, and France) are consistently and intentionally jumbled in this piece. The concept of heterotopia works well, then, as a way to consider the vast scope of imagery used in Gyatso’s installation, but specifically within his centerpiece of the Instashrine. Gyatso’s insistence on including the messy, layered, organic, idiosyncratic, as well as the automated and mechanized mass-produced material within his artistic creation is not simply an aesthetic choice, but points to a larger world where devotees include these elements in their actual shrines. Thus, his Instashrine, and the larger installation of which it is a part, pays homage to a world where mass-production and mechanization of religious objects and sound plays a meaningful part of people’s aesthetic and devotional lives among Tibetan communities, both indigenous and exiled. Through this installation, Gyatso creates a microcosm that embodies the political, commercial, and religious elements of realities for Tibetans living in the TAR, as well as in diaspora.

Shrines in the Artist’s Mileu

Though not dominant, the shrine motif is notable in Gyatso’s work as early as 2003 when he created his photographic series My Identity. In 2014 he expanded the series by adding a fifth photograph, which also includes a shrine. By 2018, Gyatso’s Buddha’s Picnic features the motif of the shrine as a central part of his installation. In all these works, Gyatso uses the shrine as a backdrop against which he probes identity issues in relation to colonization and diaspora.

Originally conceived as a series of four photographs, My Identity portrays a Tibetan artist[24] sitting cross-legged on the floor, painting on a traditional thangka canvas: a piece of primed cotton stretched over four wooden stays. The subject matter of the painting changes in each photograph, as does the artist’s environment and presentation. Of these four photographs, two feature a shrine-like assemblage. At the center of My Identity no. 2, sits the artist in a Red Guard uniform (fig. 23).[25] Slightly in the foreground and to the right of the picture frame is a closed cabinet on which Gyatso positioned a plaster bust of Mao sitting atop four red books, which represent the Quotations of Mao Tse-Tung—more commonly known as The Little Red Book, first produced in 1964. The books and plaster bust, both icons of communist China, are coupled to create a shrine to Mao.[26] Certainly, Gyatso’s own experience would suggest that his inclusion of Mao’s bust and The Little Red Book are indices of his own history when as a young child he had to memorize the contents of this handbook.[27] The altar to Mao raises questions resonant with what Gyatso later addresses in Instashrine. In both, for instance, the symbol of the Red Guard is not other to him, but part of his life as a Tibetan growing up in the Cultural Revolution.

Figure 23: My Identity 2, 2003, C-print 61.5x78cm, courtesy of the artist

In My Identity no. 3; the artist is in exile somewhere in India or Nepal sitting on a cracked concrete floor and surrounded by corrugated metal siding (fig. 24). The red suitcase, adorned with a sticker of the Tibetan flag, serves as a make-shift altar space to prop up a framed photo of the Dalai Lama adorned with kathas (Tib. Ga btags): long, white ceremonial scarves. A bundle of incense wrapped in orange cellophane stands before the framed photo. The shrine is simple yet poignant and evokes the many realities of first-generation-exiled Tibetans. [28] The suitcase reminds us of the reality of displacement that Tibetan refugees experience, and makes the viewer wonder about all that this artist had to leave behind, including family-owned shrines and objects associated with maintaining the life of shrines, such as butter lamps, statuary, imagery, and the like.

Figure 24: My Identity 3, 2003, C-print 61.5x78cm, courtesy of the artist

In 2014, Gyatso decided to extend the My Identity series and created a fifth portrait that shows the artist in present-day Tibet (fig. 25). While there are many details in this photograph that are worth analysis, I will limit my commentary to the large shrine-like assemblage of objects situated atop a wooden cabinet on the right of the composition. This collage of objects is another example of a heterotopic space that includes putti, a bust of a western child with alabaster skin and brown curly locks, and a pink framed photograph of the Karmapa. To the right of this photo-icon is a box for Maotai liquor, next to a small gold bust of Mao, which echoes the previously discussed My Identity no. 2 (fig. 23). On the left of the shrine is a large blue stuffed yeti-like fantastic animal, next to an advertisement for Nike sneakers on the back wall. A random collection of images covers the glass front of the cabinet: an advertisement for a silver SUV, a photo of a marijuana leaf, someone on horseback. Most interestingly, on the far left window we see a small sheet of white paper with red figural forms, a page of stickers from Gyatso’s “Sticker-me Buddha,” stickers; these are the same stickers he used on the Instashrine of Buddha’s Picnic in 2018. I asked Gyatso why he incorporated these stickers in the 2014 portrait; he said: “I thought the stickers would be there because the artist in Lhasa might know of this other artist’s work.” He takes this moment to clarify that the artist in the photograph “isn’t me.”[29] Rather, the artist in his My Identity series is a construction and conflation of Tibetan contemporary artists. Gyatso uses the stickers on this shrine to signal an imagined network of Tibetan artists, like those in the series, who create and reflect images of Tibetanness.

Figure 25: My Identity 5, 2014, C-print 61.5x78cm, courtesy of the artist

It is notable that Gyatso chose not to incorporate mechanical elements in the three shrines that appear in his My Identity series. By the time he creates Buddha’s Picnic, four years after My Identity no. 5, he goes headlong into the mechanized world of the sacred. And one has to wonder what catalyzed such a profound shift in his imaging of the shrine space. The answer is based, in part, on the fact that Gyatso moved to Chengdu with his family in 2017. He explained that in Chengdu “…shrine objects are everywhere. They are lying on the street to load up into a truck that hauls them off to another store somewhere in China. What’s the point?” he asked with a sense of discouragement and true perplexity. While Gyatso questions the role of these mass-produced, plastic, and mechanical materials in the shrine world, he does not lose sight of their possible benefits. He explains that there is something practical and good about the increased accessibility to and affordability of these shrine materials for people without a lot of means. “It is also good. People, all people, can afford to make a shrine, if they want one. This accessibility is important.” Indeed, the idea of accessibility becomes one of the guiding principles of his work in Buddha’s Picnic. He offers this shrine, and the larger installation, to the uninitiated, people like himself, as a kind of playground for exploration, but also for sobering reflection. Consequently, Buddha’s Picnic rides a potent tension between lighthearted play and somber contemplation, between cheeky references and painful relations.

Conclusion

Over the last fifteen years, Gyatso has carefully and judiciously used the motif of the shrine or altar as a site for reflecting and refracting complex socio-historical realities of Tibetan life since China’s colonization of Tibet in the twentieth century. The Instashrine of Buddha’s Picnic is his most elaborate study of the shrine as heterotopic space; it has become a site where he reuses religious imagery and material culture of actual Buddhist shrines neither to create a blasphemous image, nor to generate a space of numinous sublimity.[30] Rather, Gyatso’s careful reuse of religiously charged and mechanically reproduced objects works to destabilize preconceptions about Tibetanness, to probe the commodification and mass-production of Tibetan Buddhism (a process even he is critically engaged in), and to highlight complex socio-historical moments within the Tibetan Autonomous Region. He does this deftly within a carefully constructed space that not only inverts the very religious motifs he is working with, but even subverts the hallowed gallery space and experience. Through Gyatso’s installation, he invites us to play, almost irreverently, within his installation and pushes us to think about the complexities and idiosyncrasies of the shrine with its flashing lights, mass-produced objects, and tinny sounds, and its overlapping commercial, political, and religious spheres. His juxtaposed images and sounds create a thought-provoking installation that provokes the viewer to contemplate the heterotopic reality of tensions and dissonances that is disarmingly playful and at times heartbreakingly bleak.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to Gonkar Gyatso who patiently communicated with me on the phone, over Skype, We-chat, e-mail, and in person well over a year, so that I might be able to document as carefully and accurately as possible the process and the meaning of this installation. Without Staniar Gallery’s support, and more specifically the guidance of its director, Clover Archer, this installation would never have come to fruition. Generous funds from the Robert Lehman Foundation and Washington and Lee University’s Provost Office made it possible for Staniar Gallery to bring Gonkar Gyatso to campus, as well as to support his travel to the Smithsonian and Asian Society in 2018 to discuss this new installation. An earlier draft of this paper benefitted tremendously from two guest lectures I gave—one at the University of Vienna and the other at St. Joseph’s University, Philadelphia. Lastly, I am very grateful to my colleague Dr. Emily Hage who provided incredibly useful and thoughtful feedback on two drafts of this paper.

Works Cited

Alexandrova, Alena. Breaking Resemblance: The Role of Religious Motifs in Contemporary Art. Fordham University Press, 2017.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, New York: Schocken Books, 1969

Chiu-Sam, Tsang. “The Red Guards and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.” Comparative Education 3, no. 3, 1967,pp.195–205, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3097988.

Cüppers, Christoph, et al. editors. Ulrich Pagel, and Leonard van der Kuijp, eds. Handbook of Tibetan Iconometry. Brill, 2012

Dalton, Jacob. “The Early Development of the Padmasambhava Legend in Tibet: A Study of IOL Tib J 644 and Pelliot Tibétain 307.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, 124, no. 4 2004, pp. 759–72.

Foucault, Michel. (1998a) [1967] ‘Different Spaces’, in J. D. Faubion (ed.), Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Essential Works of Foucault, Volume 2, pp.175-185.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An archaeology of the Human Sciences. Editions Gallimard, 1966.—, and Jay Miskowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics, 16, no. 1 1986, pp.22–27.

Gonkar Gyatso. Personal interviews by Melissa Kerin on August 2017, January 2018, February 2018, May 2018.

Harris, Clare. In the Image of Tibet: Tibetan Painting after 1959, London: Reaktion Books Ltd.1999: 82.

—. “The Buddha Goes Global: Some Thoughts Towards a Transnational Art History.” Art History, 29 (4), 2006, 698-720.

“Let the Red Flag Fly Over Tibet Monasteries: Communist Chief.” https://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3029899/Let-red-flag-fly-Tibet-monasteries-Communist-chief.html.

Leung, Beatrice. “China’s Religious Freedom Policy: The Art of Managing Religious Activity.” The China Quarterly, no. 184, 2005, pp. 894–913.

Maniglier, P. “The Order of Things” in A Companion to Foucault. Edited by Christopher Falzon et al. 2013, pp.104-121.

Powers, John, ‘Introduction’, The Buddha Party: How the People’s Republic of China Works to Define and Control Tibetan Buddhism (New York, 2016).

Scannell, Paddy. “Benjamin Contextualized: On ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in: Katz, E., Peters et al. (ed.) Canonic Texts in Media Research: Are there any? Should there be? How about these?, 2002 pp. 74-89.

Tsering Woeser. Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, Locus Publishing, 2013.

Volland, Nicolai. “Translating the Socialist State: Cultural Exchange, National Identity, and the Socialist World in the Early PRC.” Twentieth-Century China 33 (2), 2008, 51–72. doi:10.1179/tcc.2008.33.2.51.

[1] Gonkar Gyatso, Skype conversation with author, August 2017.

[2] This installation was generously supported by Washington and Lee University’s Provost Office and a grant from the Robert Lehman Foundation for the Arts.

[3] Tibetan Buddhist art has a highly codified system of measurement for each Buddha and Bodhisattva type. These measurements are carefully explicated in texts and diagrams to assist the sacred artist in creating proper and therefore efficacious Buddhist images. See for instance, Handbook of Tibetan Iconometry: A Guide to the Arts of the 17th Century Edited by Christoph Cüppers, Leonard Van Der Kuijp, and Ulrich Pagel. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

[4] In fact, these overly aestheticized museum shrine-rooms found at the Sackler Gallery and what was the Rubin Museum, are in part what Gonkar Gyatso was responding to in this installation. His disordered, heterotopic composition of an altar/shrine stands in stark contrast to pristine museum confections with piped in chanting and low lighting.

[5] Gonkar Gyatso, In conversation with the author, January 2018.

[6] Ibid., This term was then later used as the title of the piece Gonkar Gyatso gifted Washington and Lee University.

[7] Gonkar Gyatso Skype conversation with author, August 2017.

[8] Gonkar Gyatso in conversation with the author, February 2018 (during installation process), Lexington, VA

[9] During and after this installation, many gallery visitors asked if Gyatso’s artistic creation served as an actual shrine. The artist explained in various contexts that this was a piece of art. Though reflective of current trends of actual shrine making in China and Tibet, he presented it as a secular art object that would never be consecrated or used as a real shrine. Nonetheless, he was intrigued by how people were drawn to respond to and engagement with Instashrine as if an actual shrine.

[10] Michel Foucault, and Jay Miskowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics16, no. 1 (1986): 24.

[11] For a well-wrought discussion of this term see P. Maniglier “The Order of Things” in A Companion to Foucault. Edited by Christopher Falzon, Timothy O’Leary, Jana Sawicki. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013: 104-121.

[12] Michel Foucault, and Jay Miskowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics16, no. 1 (1986): 24

[13] Ibid

[14] Nicolai Volland, “Translating the Socialist State: Cultural Exchange, National Identity, and the Socialist World in the Early PRC.” Twentieth-Century China 33 (2): 51–72, 2008.

[15] It is required that monasteries and other religious buildings in the Tibetan Autonomous Region prominently fly the red PRC flag. See Powers, ‘Introduction’, The Buddha Party: How the People’s Republic of China Works to Define and Control Tibetan Buddhism (New York, 2016).

[16] Such a sentiment evokes Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” It should be noted, however, that Gonkar’s uncertain relationship with mass-produced and mechanically operated shrine objects is rooted in anxieties and concerns that are different from Benjamin’s. In Benjamin’s essay, he questions the culture of mass production and the effect reproduction has on the originality and aura of an art object. His essay and sentiments were deeply related to the complex political situation of Europe in the 1930s with the sharp rise of fascism and Nazism and potential political gain of mass-produced art such as photography and film. For more on the specific historical context to which Benjamin was responding see Paddy Scannell, “Benjamin Contextualized: On ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’” in: Katz, E., Peters, J.D., Liebes, T. and Orloff, A. (ed.) Canonic Texts in Media Research: Are there any? Should there be? How about these? Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002: 74-89.

[17] See Beatrice Leung, “China’s Religious Freedom Policy: The Art of Managing Religious Activity,” in The China Quarterly, no. 184, Dec. 2005, 894-95.

[18] Gonkar Gyatso, Communication with Author, March 2018, Lexington, VA. Gonkar also mentions his grandmother’s shrine when he spoke at the Smithsonian’s Freer/Sackler. Go to 24:30 https://www.si.edu/es/object/yt_IwwEsuhiW5A

[19] Woeser, Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, Taiwan: Locus Publishing, 2013. In this book she publishes scores of photos documenting the activities of the Red Guard in Tibet during 1966-76.

[20] Gyatso asked similar questions about ethnicity and identity in his installation, Family Album, at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, 2016.

[21] Jacob Dalton, “The Early Development of the Padmasambhava Legend in Tibet: A Study of IOL Tib J 644 and Pelliot tibetain 307 in Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol 124., No. 4 (Oct-Dec 2004) pp. 759-772.

[22] Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An archaeology of the Human Sciences, Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005, XIX (first published Les mots et les choses, Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1966). The word only appears twice in the preface, and the entire book.

[23] One of the complications of this very participatory installation, where gallery goers are asked to engage with the environment, was having visitors know the limits of their interaction. At points, viewers would turn the music down or just keep one track audible while turning the volume low on others. People sometimes chose to hear monastic chants over pop music and vice versa. The issue, however, is that all of the music was supposed to be heard at the same time to create a dissonance.

[24] It is important to recognize that Gonkar Gyatso does not conceive of the artist in this series as himself. Rather it is an artist who takes on many identities and shifts based on his cultural environs and historical moment. This insight became clear while in conversation with Gonkar about his My Identity no. 5 photograph. I assumed he was depicting himself as an artist in Lhasa in 2015, but he explained that was not the case.

[25] In Buddha’s Picnic, Gyatso carefully positioned a statue of the Red Guard at the outer corner of the altar. Certainly, the period of the Cultural Revolution 1966-76, was an influential one for Gyatso, who would have been five years old at its onset and would have come of age during the next ten years of the revolution.

[26] As Chiu-Sam Tsang wrote in 1967: “Now it becomes a fashion or even a ‘must’ to have Mao’s works displayed prominently on one’s desk, to hang Mao’s picture in a respectful place in one’s room, and to post Mao’s sayings on the walls of one’s home and office. These are the outward signs of study.” Tsang Chiu-Sam, “The Red Guards and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” Comparative Education, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Jun., 1967): 196. Tsang’s thoughts were written at the very beginning of the 10-year revolution reflect the tenor of that time, though he was a critical voice of the Cultural Revolution safely writing from Hong Kong.

[27] Clare Harris, “Buddha Goes Global: Some thoughts towards a transnational art history” in Art History, 29 (4): 717.

[28] Clare Harris first discusses the popularity and near ubiquity of the Dalai Lama icon in 1999. “The fact that the Dalai Lama photo-icon now presides over everything from the diners in Dharamsala restaurants to the private spaces of refugee homes is the result of adaptation to the host culture of India but also of ideological battles fought in the visual field during the 1960s and 1970s in Chinese-controlled Tibet.” In the Image of Tibet: Tibetan Painting after 1959, London: Reaktion Books Ltd. 1999: 82.

[29] Gonkar Gyatso, in phone conversation with author, February 26th, 2018.

[30] These are two foci of this discussion about religious imagery and motifs used in contemporary art. See for instance, Alena Alexandrova, Breaking Resemblance, New York: Fordham University Press, 2017: 82-87; chapter 4. Notably, however, her discussion about religious imagery in contemporary secular art primarily pertains to Western artists and religious traditions.

Melissa R. Kerin serves as the director of the Mudd Center for Ethics at Washington and Lee University, where she is also a member of the faculty of Art and Art History. Kerin holds a Ph.D. in Art History from the University of Pennsylvania and an M.T.S. from Harvard Divinity School. Along with number of articles and chapters, Kerin has authored two books. She is currently working on a new monograph, Bodies of Offerings: The Materiality and Vitality of Tibetan Shrines, which received an American Council of Learned Societies Fellowship and Howard Foundation Fellowship. Kerin is also working on a project entitled Turbans and Turquoise: Patron Portraits in Ladakh’s Basgo Village supported by a National Endowment of the Humanities Summer Stipend.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities