ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Hybridity and Pilgrimage in Chögyam Trungpa’s Concrete Poetry

Matilda Perks

Abstract: Chögyam Trungpa (c. 1940-1987), one of the earliest translators of Tibetan Buddhism outside of Tibet, was also a prolific poet. Recently rediscovered poems that he composed as an immigrant in the United Kingdom in the 1960s show that Trungpa experimented with concrete poetry, a modernist poetry movement with roots in concrete art. Concrete poetry places an emphasis on the visual features of the written word in order to achieve extra-linguistic communication. The architects of the poetic form were, in part, seeking a global language, one that would easily communicate meaning across cultures. The spirit of internationalism likely appealed to Trungpa. At the time that he began composing concrete poetry, Trungpa was at a personal crossroads. He didn’t know how to translate the Buddhadharma such that Westerners might understand it. This conundrum constituted a personal crisis for him. His overriding concern was with preserving Buddhism by spreading it in a new culture, and he felt that his life had little value otherwise. He was also haunted by the memories of his escape from Tibet to India. In the United Kingdom, Trungpa became friends with Dom Sylvester Houédard, one of the UK’s most acclaimed concrete poets and he began writing concrete poetry. Trungpa’s concrete poetry adheres to some of the genre’s main features, but it is not mere imitation. His poetry also reveals a longing for Tibet, a desire to share his refugee story, a sophisticated grasp of visual composition, and a technique of seamlessly blending Tibetan and Western literary elements.

Keywords: Chögyam Trungpa, Concrete Poetry, Tibetan Buddhism, Dom Sylvester Houédard, Buddhist Poetry

Today, Chögyam Trungpa is known for his wholehearted embrace of the “modern.” He is known for presenting a specific brand of Buddhism that was tailored to resonate with a modern audience who primarily held secular-scientific worldviews by downplaying the role of ritual and esotericism in the tradition.[i] But the archive of Chögyam Trungpa’s unpublished concrete poetry tells a different story. It tells the story of a man who rejected the traditional/modern divide and instead reveled in hybridization, injecting elements of the traditional into a modern poetic form.[ii]

Concrete poetry turns the written word into a picture; the word is meaningful both semantically and visually. Without a clear beginning or end, top or bottom, the written words’ relationship to the other words on the page takes precedence over what they refer to off the page. The poems have no beginning and no end; they are fluid, emphasizing process rather than any goal. At the same time, concrete poetry expresses a kind of authorial desire to collapse the space between words and their objects, to make the written word not a device that points, not a symbol, but the thing itself. Chögyam Trungpa’s concrete poetry expresses an aching and sometimes playful desire to construct a new world.

It is understandable then that Chögyam Trungpa experimented with concrete poetry during one of the most difficult periods of his life. Circa 1969, Trungpa, a young Tibetan refugee, was living and serving as the resident lama and co-founder of Samye-Ling Meditation Centre, a Tibetan meditation center located in the moorlands outside the tiny village of Eskdalemuir in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. That spring, while driving in Northumberland, Trungpa ran his car off the road, crashed through the front door of a joke shop, and almost lost his life. Instead, he lost the use of the left side of his body. He emerged partially paralyzed and lived with this physical disability for the remainder of his life. From a hospital bed in Newcastle he wrote a poem:

The old traveller,

Stumbling with his stick’s support

Makes the journey of pilgrimage.

Each step is not perfect.

Walking on the desert sand,

His foot slips as he walks. (Mudra 46)

It is clear that Trungpa is the old traveller and his life is the pilgrimage. Before his accident, Trungpa had been flirting with the idea of radically transforming the direction of his life, but he had not found the resolve he needed to make such a move. Regaining consciousness under florescent lights, in a hospital bed, with a walker beside him, he decided he could no longer equivocate. He wanted to make a radical break from his past. He wanted to “transcend cultural boundaries” (Born in Tibet 255). And he wanted to give up his monastic vows and marry.

He later described these three events—the accident, his resulting decision to disrobe, and his decision to marry—as an experience of being painfully stripped not just of his monasticism and culture, but of his very flesh.

You [are] not only stripped out of your monk’s robes, celibacy, but you’re also stripped out your skin and your flesh. You are [a] walking skeleton—[you are] still alive and your heart is not stripped out, your brain is not stripped out—apart from that everything’s stripped out, which is a fantastic experience. And [on top of that] you are not stripped out in your own culture, but you’ve been stripped-out in [an] alien culture, full of pollution, motorcars, airplanes, jets hovering above your head, and people gossiping about you, murmuring. [It] is an extraordinary stripping-out process. (“Jamgön Kongtrul Seminar” 00:42:47)

Biography

Born in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands of eastern Tibet, in Kham, Trungpa was a child of nomadic parents. The winter that he was born, his family was settled in an encampment on a high grassy plateau in a province historically ruled not by Lhasa or Beijing, but by a local king. Because of the high altitude, the region grows no trees or bushes to protect from the winter’s severe weather. In the coldest months, when ice covered the ground, Trungpa’s family camped in a village of about five hundred people, continuously burning a fire in the center of their black yak-haired tent to keep the frost at bay. In the summer months, when the plateaus bloomed with wild grasses, flowers, and herbs, they packed up their belongings and moved with their animals. Trungpa’s mother, Tungtso-drölma, gave birth to him in a cattle-shed in February of circa 1940 (Born in Tibet 25).[iii]

From his infancy, Trungpa’s parents intended for him to be a monk. A local lama, who visited a few months after the child’s birth, gave the infant a special blessing and told the family that they should send the boy to his monastery for an education. Roughly one year later, when the child was about eighteen months, a search party from a different monastery, Surmang Dütsi Tel, arrived at the encampment looking for the reincarnation of their previous abbot, the tenth Trungpa. They recognized Tungtso-drölma’s son and quickly made plans to install him as the future abbot of Surmang Dütsi Tel (Born in Tibet 25).

In 1951, Tibetan authorities signed the Seventeen-Point Agreement with Beijing. The treaty incorporated Central Tibet into the People’s Republic of China under the condition that Tibetans maintain some measure of regional autonomy. Beginning in 1952, Tibetan autonomous regions were created along the eastern areas of Tibet. Mao Zedong’s rural collectivization policies incited uprisings and a wave of refugees from Amdo and Kham began to pour into Lhasa. As the PRC incorporated these regions into its territory, the Khampa (the people of Kham) mounted a coordinated armed resistance, eventually receiving funding from the C.I.A. (Gros 31-32).[iv]

Eventually, the fighting reached Surmang Dütsi Tel. The People’s Liberation Army held the monastery as a strategic operations center for about a month. The monks and senior lamas who failed to escape or join the resistance were imprisoned or sent to labour camps. Trungpa went into hiding.

In March of 1959, while debating whether or not bold action was required, Trungpa’s party received news that the Dalai Lama had fled Tibet for India (Born in Tibet 170). This news cemented the group’s decision to leave Tibet. Trungpa Rinpoche and his closest friend, Akong Rinpoche, along with approximately 80,000 other Tibetans, attempted a last-minute escape. They tried to travel light to escape detection, but as the news that they were escaping circulated, more people joined them. Their flight took nearly nine months. They travelled quietly, tried to stick together, rarely making fires. Their journey took them across the tallest mountains in the world. The PLA fired on them when they crossed the Brahmaputra River. Wild animals killed and mauled their horses. They ran out of food in foreign terrain, not knowing which plants might be edible. With no village or help in sight they considered surrendering to the Communists, hoping, at this point, to be discovered before they starved. “Be a strong Khampa and don’t lose heart” became their motto as they willed themselves to push on. In desperation, the group resorted to cooking the leather they had on their persons for food (Born in Tibet 230-248).

Trungpa saw his flight as a pilgrimage; he and the convoy of refugees were walking to India, the birthplace of Buddhism, the motherland. He told himself that he was fortunate to be able to make the journey. “Each step along the way,” he said to his fellow refugees, “should be holy and precious to us” (Born in Tibet 208).

Eleven years later, discussing his escape with a class of undergraduate students at Colorado University, he said:

It’s very beautiful to really cross these mountains, and once you cross one mountain you suddenly discover a beautiful blue lake behind it. And you go on and on. You find precipices and mountains, glaciers, and beautiful things. It’s very extraordinary. We climbed up—up to about twenty thousand feet . . . high up [in the] mountains . . .

Here he took a long pause. When he spoke again his voice was quiet, inward, as if he was speaking to himself

I thought of going back to Tibet and making the same journey again.” (“Colorado University Class” 00:48:43)

The incongruity between escaping a war-torn country in fear and simultaneously enjoying the scenery, hoping to make the trip again, perhaps struck the crowd as absurd. Laughter erupted. Snapping out of his reverie, Trungpa melted into laughter too.

Nevertheless, Trungpa committed himself to the view that their escape was a pilgrimage. This perspective recast his experience from that of a victim of political violence to that of an agent of a spiritually beneficial act. The practice of pilgrimage is most often translated from the Tibetan words nékor and néjel. The former refers to circumambulation (kor) of a holy site (né), and the later refers to meeting or seeing such a site (Huber 60-61). In the practice of pilgrimage, not only the holy site itself is sacred; the landscape around that site is also understood to carry religious significance and power. In The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage & the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India, Toni Huber explains: “Tibetans consider the actual physical environs and substances of any Buddhist né to also embody the same sacred and moral qualities of enlightened being, as if they had suffused or permeated the surroundings” (61). In undertaking a pilgrimage, it is not just the landscape surrounding the né that can hold significance but the landscapes that the pilgrim passes through on the way to that site. Even the preparations before the journey can be infused with sacred meaning. The poem that Trungpa wrote from his hospital bed in Newcastle suggests that although he had at that point already reached India (and departed from it) he continued to cling to the idea of pilgrimage. The circumstances of his life had acquired the patina of the pilgrimage. His life became an extended pilgrimage—a pilgrimage detached from a site, perhaps: a spiritual quest sans né.

After losing members of their original party, Trungpa and some of his friends found safety in an Indian refugee camp. However, they failed to find freedom there. The refugee camp in Misamari where Trungpa and his friends sheltered was overflowing with recent Tibetan refugees. Each of the camp’s newly constructed bamboo huts housed as many as one hundred refugees. Illness spread throughout the camp no doubt owing to the Tibetans’ vulnerability to India’s unfamiliar climate and pathogens, coupled with overcrowding and the hardship that the asylum seekers had endured during their escape. Many Tibetans fell ill or arrived ill at the camp. Those who were able worked during the days on road construction crews (McGranahan 127-129). Trungpa and his friends eventually managed to escape the camp. And in time, Trungpa and Akong found their way to the United Kingdom, unsure of what they might discover.

Encountering Representations of the Tibetan Other in Europe

Akong and Trungpa were some of the earliest members of the Tibetan vanguard in Europe. They quickly discovered that Tibet holds a special, if heavily stereotyped, place in the Western imagination. European mythologies often treat Tibetans as incidental, minor figures in a story about the Western discovery of esoteric, rarified, or lost wisdom. When Tibetans figure in these stories, they are guardians of knowledge that the European is entitled to. The relationship between Europe and Tibet was primarily extractive; Europeans fantasized about the treasures they might mine from contact with Tibet.

In his book Prisoners of Shangri-La, Donald Lopez Jr. traces the genealogy of Western representations of Tibet, Tibetans, and Tibetan Buddhism. The law of opposites, he finds, is prevalent throughout this history: Tibet is represented as a either paradise or a prison; Tibetans are spiritually sophisticated or backwards—polluted or pure; Tibetan lamas are either despots or enlightened liberators; Tibetan Buddhism is either a degraded, monstrous form of Buddhism, or its most advanced expression. When Tibet became an object of European colonial desire, Tibet was painted as inaccessible, mysterious, and unknown, a designation that, Lopez observes, has significance only when Tibet is compared to forcibly opened China (4-10).

Tibet was (and is) often represented as outside of history, ancient, timeless. The Theosophists believed Tibet was the sanctuary of the Mahatmas, the great ascended masters who held the knowledge of Atlantis. But Tibetans, the Theosophists insisted, were unaware of the presence of the Mahatmas in their land. Likewise, James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizon features a several-hundred-year-old Belgian Catholic missionary who stores the treasures of Western civilization in a Tibetan monastery, Shangri-La, in order to safeguard these jewels against the ravages of modernity for future generations. Shangri-La is run by a society of foreigners, and Tibetans are largely unaware of the organization’s mission. They are painted as incurious, content to live their humble lives (Lopez 5).

The European imagination is both enthralled and repulsed in equal measure by esoteric knowledge from the East. Alarm about “Oriental despots” has enthralled the Western imagination since the nineteenth century (Lopez 6). Victorian England was captivated by the image of Svengali, the charismatic hypnotist who gains access to a susceptible, weaker mind (i.e. primarily a woman’s mind) and exploits that victim’s vulnerability for sexual and monetary gain. Histories of hypnotism in late Victorian England place the origins of the practice primarily in Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and Australian Aboriginal cultures (Pick 132). However, the practice of hypnotism was introduced to Europe by the Viennese alchemist, musician, and medical student, Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815). Mesmer’s interest in the healing powers of magnets sparked an enduring “mesmerist” movement in Europe, a phenomenon that coincided with widespread panic about the danger of charlatans misusing that power. Inevitably, English fears about the dangers of hypnosis merged with the racialized other (Pick 44–50).

Daniel Pick discusses this connection in Svengali’s Web: The Alien Enchanter in Modern Culture. The fictional character of Svengali, a German-Polish Jew, was created by the Anglo-French writer George Du Maurier. In Du Maurier’s popular novel Trilby, Svengali hypnotises a young vulnerable model of Irish descent, making her his wife as well as an international opera star. In the story, Svengali’s Jewishness precludes him from being an object of uncoerced desire, a detail that makes his powers of persuasion all the more impressive (Pick 3).

So it is understandable that the figure of the sinister Svengali was foremost in the mind of Trungpa’s future mother-in-law when she and Trungpa first met. The upper-class British woman visited Trungpa’s meditation center Samye-ling in the late 1960s, attended by her two teenage daughters. After a few days of an otherwise pleasant visit, her daughter Diana, Trungpa’s future wife, found her mother “sitting on the bed, absolutely frozen. She seemed to be in shock. She didn’t move or say anything for several minutes. Then she said, ‘My God, I’ve been hypnotized. I’ve been hypnotized by this Asian. Pack your bags immediately. It’s black magic. We have to get out of here’” (Mukpo 10).

Confronted with these stereotypes, Trungpa said that wearing the maroon monastic robes of the Tibetan tradition in the United Kingdom made him feel alien. Recalling his experience studying at Oxford, he explained that it was “the first time I had been the object of that fascination which is non-communicative and nonrelating, of being seen as an example of a species rather than as an individual: ‘Let’s go see the lamas at Oxford’” (The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume One, 280).

In the West, a robed Tibetan might be regarded as spectacle, but to the extent that the monastic life has purchase on a rarified morality, it also confirms Western expectations about spirituality. In this way, monasticism is accompanied by a certain positive stereotype that might endear displaced Tibetan clergy to Westerners. Monasticism could therefore be a useful political tool for drawing sympathetic Western support to the Tibetan cause. But Trungpa was primarily interested in communicating Buddhist teachings to potential converts, and he believed that whatever measure of influence he might gain from the aura of spiritual authority cast by his monasticism would be eclipsed by the sheer fact of his otherness. Taking off his robes, he hoped, would allow people to see his humanity.

“I have decided to give up the robe,” he wrote, “which I feel stood as a subtle obstacle to the formulation of my teaching in the West. The monk’s robe confused many here as a glorious image of spirituality. However, my teaching concerns actual experience. I don’t feel that I need to hide behind something, though some people are critical of me for coming out and showing myself as a human being.” (qtd. in Mukpo 26)

Trungpa’s solution to overcoming the othering gaze of the Anglo-European involved dodging the idea of “glorious spirituality” altogether, disrupting that fantasy and “coming out” as human—as flawed and ordinary.

The way that Trungpa wanted to live and teach—his desire to disrobe, and his increasing appetite for experimenting with transmitting the Buddhist teachings—instigated a serious and lifelong conflict with Akong, who was more cautious and less inclined to deviate from tradition. Trungpa’s decision to disrobe also alienated many of his students and benefactors. Although it was not his first time stepping out of his monastic vows, it was the first time he proposed to do so publicly. Trungpa had not practiced celibacy for several years. During his escape from Tibet, Trungpa fell in love with a nun who was a member of their party. They met again in India and conceived a child. In England, he also began binge drinking. His wife, Diana Mukpo, recalled that following his accident, when he finally gave up wearing robes, he felt “abandoned” and “misunderstood” by both his Tibetan friends and his Western students (25-26). She later remembered:

The period from Rinpoche’s accident until we married and left for America a year later was one of the darkest times in his life. Rinpoche was often in the depths of depression. He was sick with pleurisy and pneumonia, he was crippled, his Tibetan compatriots were trying to control him, and many of his students had left him. He felt that his only reason for existence was to present the Buddhist teachings. Akong refused to support him in teaching the way that he wanted to, and he had very few students in England who could hear what he had to say. For Rinpoche, if he had no opportunity to present the buddhadharma, the Buddhist teachings, life was not worth living. He told me at several points that if he couldn’t teach, he had no reason to go on. (27)

Trungpa and Concrete Poetry

During this difficult period, Trungpa found time to sit by himself at a typewriter that had red-and-black ink ribbons. Using the colors interchangeably, he experimented with a new poetic form.

‘Concrete Poem 2’. Courtesy of Diana J. Mukpo. All Rights Reserved.

‘Concrete Poem 3’. Courtesy of Diana J. Mukpo. All Rights Reserved.

It is likely that Trungpa first encountered concrete poetry after he was introduced to poet, philosopher, and Benedictine monk Dom Sylvester Houédard (often known by his initials dsh). The two met in the early 1960s, and Houédard encouraged Trungpa’s experimentation with the poetic form (Thomas 191).[v] By 1964, concrete poetry was creating waves in England and Scotland. Over the following decade, Houédard established himself internationally as a leader of the genre.

Concrete poetry originated in Brazil and Germany in 1955 when Brazilian poet Décio Pignatari met the Bolivian-Swiss poet Eugene Gomringer in Ulm, West Germany. Pignatari was the founder of the Noigandres poetry collective in São Paulo and Gomringer worked for the founder of concrete art, Max Bill. Pignatari and Gomringer discovered that they shared a similar orientation to poetry, and they decided to name their unique work “concrete poetry” (Thomas 23). Their early influences included concrete art, semiotic theory, modernist architecture, constructivist art, cybernetics, sound poetry, and Ernest Fenollosa’s The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry. Early concrete poets were concerned with the newly globalized post-war reality they found themselves in. Concrete poetry served a social agenda too. The poets were interested in creating a new, universally understood language, one that might facilitate transnational communication and thus remedy the fevered nationalism, fascism, and genocidal global conflict that had marked the previous decades. It follows then that at its start, concrete poetry was deliberately minimalistic in order to facilitate accurate communication (Thomas 22-37).

The form morphed as it gained popularity. In Houédard’s hands, the concrete poem transcended language altogether. Houédard created three-dimensional designs on the page, using letters and diacritic marks. Trungpa’s work is not like Houédard’s, though, in the sense that he never abandoned semantic meaning. Although Trungpa’s poetry binds the word and the image together, his poems still rely on semantic meaning. They do not draw a picture independent of the word’s meaning à la Apolloniare.

Trungpa’s work demonstrates a concern with the musicality of language—its sonic elements. It also seems that he wanted to share his personal experience. The concrete poets’ aspiration to communicate transnationally echoed a prevailing concern that Trungpa had at the time. He was determined to communicate what he had inherited from his Buddhist training across cultures.

Trungpa’s unpublished concrete poems are also minimalistic in how they preserve negative space on the page. Like Houédard, Trungpa was interested in “the gap” —the inexpressible—and its religious and aesthetic possibilities. In Buddhist terminology, the gap roughly maps onto the principle of emptiness or śūnyatā. For Houédard, the gap communicates, in part, negative theology—finding God through negation (Thomas 172). Houédard evokes the gap by filling his page with diacritics and leaving small spaces here and there. But Trungpa’s page is the reverse: space dominates, and the keys’ impressions are incidental.

Trungpa’s poems are also a meditation on landscape. He wrote himself into different landscapes, including those of Tibet. “Life,” he wrote at the top of an empty sheet of paper, “Was as it was.” He positioned the next words on different planes of the page: “moon” hangs at the top, “me” hovers in the middle of the page, and the words “rock” “grassssssssssssssss windgrass” are placed underneath (Mudra 52).

Trungpa published Life Was as it Was in his 1972 collection of poetry entitled Mudra. The picture it paints is as evocative as it is unembellished. The heading provides some context. The poem is located in a past that was elemental: there was wind, grass, wind-grass, a moon, and Trungpa himself.

The archive of Trungpa’s poetry is filled with handwritten poetry scrawled on yellowing sheets of lined notepaper. By contrast, his concrete poems are always typed on a typewriter.[vi] In Designed Words for a Designed World: The International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971, Jamie Hilder asks how a visual poem composed on a typewriter means differently than one composed by hand. Hilder argues that there is something unmistakably modern about the visual poetry of the time. Concrete poetry was a response to the proliferation of new media such as photography, print, television, newspapers, billboards, and neon lights. Hilder notes, “Concrete poetry drew the reader’s attention to the materiality of language, to its physicality, and its changing role within global communication. The dematerialization of the art object mirrored the rematerialization of the word: the canvas became a page and the page became a canvas” (14-15).

Like Trungpa, concrete poets of Trungpa’s time composed in the Roman alphabet. Hilder argues that there is something “ideologically modern” about the choice to compose this type of poetry in the Roman alphabet. “[T]his flight from language takes place predominantly within the Roman alphabet, completely eliding Cyrillic, Arabic, and most of the Asian ideogrammatic languages and thus making the work ideologically modern and inextricable from certain cultural, economic, and military infrastructures” (19).

But the content of Trungpa’s poetry conveys an uneasy or, at the very least, an incomplete embrace of the modern. His poems are mostly landscapes. Aside from one poem that depicts military aggression, the landscapes are untouched by industrialization, capitalism, colonialism, modernity.[vii] The use of technology to make the poems contrasts with their images of the natural world. This juxtaposition is enhanced in the unpublished poem depicting, simply, a stone dropping into a pond (‘Concrete Poem 4’). The images convey both a tension between the mechanized and the natural and a slippage between them. The modern includes and occludes the premodern at once. The space that is created is one of in-betweenness. A typewriter is being bent into a brush.

‘Concrete Poem 4’. Courtesy of Diana J. Mukpo. All Rights Reserved.

When Trungpa writes himself into the picture, he is alone in a landscape. In an unpublished, untitled poem, he is alone in a bamboo hut, at the base of a mountain. The words “me alone” are typed in red ink. This poem is composed on the back of a folded piece of paper. On the front side are two Christian hymns, the first by Samuel Longfellow, the second by Jane Borthwick. Maybe he received this paper as a hand-out, to help him sing along, at one of his visits to a local Christian group. Maybe he typed it himself for a class or language lesson. I imagine him stashing it inside his robe, taking it back to his room, folding it and willing himself, like an incantation, into a bamboo hut, alone, unburdened, in a small act of independence (‘Concrete Poem 1’).

‘Concrete Poem 1’. Courtesy of Diana J. Mukpo. All Rights Reserved.

In a second unpublished poem, another red-inked “me” is likewise alone, this time suspended upside down, beside a rocky cliff. The image is both humorous and dark. It suggests Trungpa’s swan dive off a high cliff. With a wink to this impression, and a nod, perhaps, to Houédard’s poem ‘Frog Pond Plop,’ the word “plop” is written across the bottom of the page (‘Concrete Poem 5’).

‘Concrete Poem 5’. Courtesy of Diana J. Mukpo. All Rights Reserved.

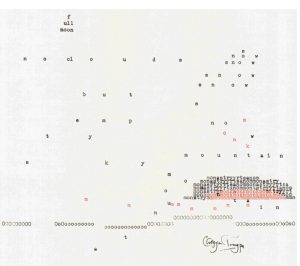

In a work that captures the agony of this period in his life, ‘Full Moon, No Clouds’ (1972) depicts a Tibetan night scene. The moon is full, the night sky is clear and empty. The harsh impression of the keys is transformed into the familiar landscape of the plateau. At the base of a snow mountain is a monastery. All of the words appear in black ink except for a constellation of red-inked “monk[s]” inside the monastery. There is one lone monk outside the monastery’s walls. He appears to be in a state of dissolution, the letters of the word are drifting apart, as if captured in the midst of a slow-motion explosion. There is a loss of gravity, a loss of coherence, and an unboundedness about this monk’s body. Although Trungpa does not explicitly write himself into this scene, I can’t help but read the piece as autobiographical, seeing Trungpa as the one displaced monk, slowly dissolving (Collected Works Vol. Seven 283).

‘Full Moon, No Clouds’. Courtesy of Diana J. Mukpo. All Rights Reserved.

Because Trungpa’s life story is full of alcohol, drugs, and sex, it is easy to imagine that he gave up his robes and never looked back. However, his poetry suggests something else entirely. He later wrote about his life’s plan: “I was going to become a simple little monk. I was going to study . . . and become a good little Buddhist and a contemplative-type person. Such a thread still holds throughout my life. In spite of complications in my life . . . ” (Training the Mind 4). Trungpa’s concrete poetry is an intricate collision of technology, landscape, emotion, past and present, all of which reveal a crossroads in his life.

The concrete poetic form breaks down the distinctions between picture and word, and as such it exists in the interstices of conventional artistic genre. The poetic form’s liminality likely appealed to Trungpa, who found himself displaced from his home and living in a perpetual state of in-betweenness. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall notes:

Diasporic experience . . . is defined, not by essence or purity, but by the recognition of a necessary heterogeneity and diversity; by a conception of ‘identity’ which lives with and through, not despite difference; by hybridity. Diaspora identities are those which are constantly producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference (“Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” 235).

Trungpa’s poems are an exercise in hybridity. In another subtle blending of one culture into another, the use of red ink in these poems occurs over and over again. In one we see the red Sanskrit syllable “OM” (rendered in Roman) and the Sanskrit term “SWAHA” (‘Concrete Poem 1’). In ‘Full Moon, No Clouds’, Trungpa uses vermillion ink—the color of Tibetan monastic robes—to nod to Tibetan tradition. The use of vermillion ink is also a common Tibetan typographical convention. Tibetan texts that feature this convention highlight certain words in red ink and some use red lettering along the edges of the page. The use of red lettering in Tibetan texts differs. In some texts red inked words serve as a mnemonic device, to aid in the memorization of the text. In other texts, the highlighted words elevate certain honorific words, and in some cases the use of red pigment appears to be purely aesthetic. The red pigment is traditionally derived from cinnabar found in Southeastern Tibet, or a synthetic mercury sulfide imported from China or India. Because of the rarity of this pigment, it is considered meritorious to produce text in vermillion.[viii]

Because Chögyam Trungpa embraced Western culture at a time when other displaced Tibetans were concerned with faithfully preserving Tibetan culture, he is sometimes understood as someone who thoroughly assimilated into Western culture. Of course, he was not particularly interested, in Hall’s words, in a “mere ‘recovery’ of the past” (Hall 225). He was proud to be the first Tibetan to become a British citizen, and he married into a British family. He also worked hard to perfect his English. As a result, he is sometimes characterized as an Anglophile. But the study of his concrete poems reveals a complex negotiation of his heritage, rather than a wholesale replacement of it. This is a story not of an immigrant seeking acceptance in a new culture, but of a person trying to weave together the East and the West, the Roman alphabet and the Tibetan landscape, the natural and the mechanical, the traditional and the modern, the spiritual and the mundane, the past and the present. These poems display a Tibetan far from the landscape that had anchored his reality, now with a typewriter and two different colored ribbons, collapsing the “traditional/modern” binary through a technique of hybridization. They tell the story of a person who was looking for a space in which identity is not singular; a space that resisted dualistic representations; a space that evaded the othering stereotypes of the Western imaginary; a landscape where life could once more be as it was.

Works Cited

Goldman, Ari L. “2,000 Attend Buddhist Cremation Rite in Vermont.” The New York Times, 27 May 1987, www.nytimes.com/1987/05/27/us/2000-attend-buddhist-cremation-rite-in-vermont.html.

Gros, Stéphane. Introduction. Frontier Tibet, edited by Stéphane Gros et al. Amsterdam UP, 2019, pp. 31-32. Open Research Library, doi:10.5117/9789463728713.

Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, edited by Jonathan Rutherford. Lawrence & Wishart, 1990, pp. 222-237.

Hilder, Jamie. Designed Words for a Designed World: The International Concrete Poetry Movement, 1955-1971. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2016.

Huber, Toni. The Holy Land Reborn: Pilgrimage & the Tibetan Reinvention of Buddhist India. U of Chicago P, 2008.

Lopez, Donald S. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West. U of Chicago P, 2018.

McGranahan, Carole. Arrested Histories: Tibet, The CIA, And Memories of a Forgotten War. Duke UP, 2010.

Mukpo, Diana J. Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Shambhala, 2006.

Pick, Daniel. Svengali’s Web: The Alien Enchanter in Modern Culture. Yale UP, 2000.

Rassool, Ciraj Shahid. The Individual, Auto/biography and History in South Africa. 2004. U of the Western Cape, PhD dissertation.

Thomas, Greg. Border Blurs: Concrete Poetry in England and Scotland. Liverpool UP, 2020.

Trungpa, Chögyam. Born in Tibet. Prajña Press, 1981.

—. The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One, edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian.Shambhala, 2003.

—. The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Seven, edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian.Shambhala, 2004.

—. “Colorado University Class: Talk Six,” 1971, Boulder, CO, MP3 file.

—. ‘Concrete Poems 1-5,’ Private Papers and Office Papers Fonds, Box PR1, Shelf 55, Precious, Restricted, Shambhala Archives, Nova Scotia.

—. Mudra. Shambhala Publications, 1972.

—. “Seminar on Jamgön Kongtrul: Talk Six,” 1974, Boulder, CO, MP3 file.

—. Training the Mind and Cultivating Loving-Kindness, edited by Judith L. Lief. Shambhala Publications, 2003.

Notes

[i] See: McMahan, David L. The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford UP, 2008, p. 8; Gleig, Anne. American Dharma, Yale UP, 2019, p. 30.

Trungpa is also widely known for his notorious “behavior,” which includes alcohol and drug abuse and sexual relationships with several of his students outside of his marriage. Trungpa’s behavior is a hot topic. A fellow student once said to me, “I don’t know if Chögyam Trungpa was the best thing to happen to Buddhism in the West or the worst thing.” A professor, referring to Trungpa’s sexual relationships with his students, told me that he thought sex was inappropriate between students and teachers. I heartily agreed. Because I was his student, I didn’t want this professor thinking I was interested in having a romantic relationship with him just because of my proximity to Trungpa’s community. But even as I agreed with that professor, I couldn’t entirely condemn sexual relationships between students and teachers because I grew up in Trungpa’s community with people who told stories about their intimate relationships with him. The stories I heard at the time had always included the narrator’s consent. In the wake of the #MeToo movement and recent clergy sexual misconduct allegations against Trungpa’s son, a couple of women have reexamined the power dynamics involved in their relationships with Trungpa. They have spoken openly about how they feel that they were not in a position to consent. At the same time, to my knowledge, many women maintain that their sexual relationships with Trungpa were consensual. Charging this latter group with false consciousness doesn’t feel righteous. It feels infantilizing.

After watching the film Crazy Wisdom (2011), about Chögyam Trungpa, an undergraduate student in my class raised her hand and asked me how I could justify studying his life. I answered by explaining that I think an important part of what Buddhism is includes what Buddhists do, and that there is a tradition of antinomian behavior in Buddhist history that Trungpa modeled himself after. I explained that it isn’t up to me to decide who is and isn’t included in the tradition. But something about her question troubles me still. It troubles me because I could tell I didn’t answer her question. I didn’t answer because I didn’t understand it at the time. Maybe she was expressing a desire to “cancel” Trungpa, but I think it was more layered than that. I think her question expressed the desire to find something pure and good to believe in. It was later confirmed that the student was hoping to convert to Buddhism. Her encounter with a history of that tradition that included a fraught, complex story (a story that is uncritically celebrated in the film that had just been shown to her) threatened to disrupt a potential site of refuge for her. Of course, the field of religious studies is not oriented towards producing religious subjects; it’s designed to produce scholars of religion. Yet I sometimes find myself torn between the desire (or pressure) to produce a “pure” object of refuge for students like this one and my conviction that such a task is neither possible nor ultimately helpful. It is only by flattening the story of the tradition I grew up in that I can make it “good” or “bad.”

Returning to the question about whether Trungpa was the best thing or the worst thing to happen to Buddhism: that is a question I am not tempted to answer. For better or worse Trungpa believed that the Buddhist tradition needed to include an element of “crazy wisdom” in order for it to survive in the future. For better or worse he lived his life (as we all do) in a storied way. He actively aligned himself with specific narratives in Buddhist history and either contextualized his past behavior within the Buddhist tradition or sought out experiences that aligned with Buddhist narratives. My research into his influence on modern Buddhism isn’t intended to be evaluative. I’m not a theologian. I’m not interested in making arguments about what Buddhism should or shouldn’t be. Instead, I’m interested in how people construct meaning out of their lives.

I’ve found that an obstacle to taking the measure of Chögyam Trungpa’s influence on modern Buddhism is precisely the pressure to perpetuate ideas about the “goodness” or “purity” of spirituality itself. In my experience, any discussion about Chögyam Trungpa often quickly becomes a discussion about what a spiritual teacher should or shouldn’t be or do: a spiritual teacher should not have sex with their students; a spiritual person shouldn’t have addiction issues. If they do, they are not considered authentically spiritual. The student who asked how Trungpa might be a legitimate object of study was asking a version of this question: how can Trungpa be an authentically spiritual person such that he deserves to be included in the subject’s study? (The distinction between spirituality and religion is outside the scope of this discussion but suffice to say I do not hold that this distinction is given. Rather, it is historically created. For instance, Buddhist modernism, which Trungpa had a hand in shaping, conflates Buddhism with spirituality and distances it from religion). On the other hand, students of Chögyam Trungpa often argue that a spiritual teacher should be unpredictable, act in antinomian ways, and upset the status quo. This point of view celebrates Chögyam Trungpa’s life as an expression of crazy wisdom. But both of these competing positions are ultimately concerned not with spirituality but with authenticity. They seek to answer the question: “what is authentic spirituality and what is inauthentic spirituality?”

Yet, authenticity assumes that individuals have a core self that they either present honestly or cloak deceitfully. Instead of hoping to discover the authentic person underneath the veil, the biographer doesn’t discover the truth about a real person behind the text; they participate in a web of competing and intersecting narratives that all produce historical meaning. In his doctoral dissertation, Ciraj Rassool argues that if biography is going to be useful for history, biographers must abandon approaches that produce untheorized life-histories, which advance narratives focused on “real” persons and “real lives.” Instead, biography should interrogate assumptions about the “coherence of character and selfhood” (28) and the coherence of a life. Just as identity is produced through historically established enunciative practices, so too the coherence of a life is “imposed by the larger culture, by the researcher, and by the subject’s belief, retrospectively (and even prospectively), that his or her life should have such coherence” (29). This article is an attempt to attend to some of the competing and intersecting historical narratives that Chögyam Trungpa was both negotiating and producing in and through his poetry.

[ii] For an autobiography of Chögyam Trungpa’s life, see: Trungpa, Chögyam. “Born in Tibet.” The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume One, edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian. Shambhala, 2003. For an abridged biography see: Samuel, Geoffrey. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993, pp. 344–49.

[iii] The discrepancy in Trungpa’s date of birth comes from a few sources. Trungpa’s widow, Diana Mukpo, puts his date of birth in 1940 (Mukpo 57), whereas Trungpa’s autobiography places his birth in 1939 (Born in Tibet 25).

[iv] For a more complete history of the Khampa’s armed resistance see McGranahan, 2010.

[v] I want to thank Angela Pressburger for bringing this relationship to my attention. She remembers encountering Trungpa’s concrete poetry in a show curated by Houédard in 1967 or 1968. Personal email communication, 4 June 2022.

[vi] Trungpa’s concrete poetry, which has heretofore been unpublished, is found in his archive unnamed and undated. For clarity’s sake, I have rendered them here ‘Concrete Poems 1-5’. This is my own invention.

[vii] One poem, however, features a recognizably modern object: three jets on the upper left-hand corner of the page release a cluster of the letter ‘b’ (bombs) over a rocky landscape (‘Concrete Poem 3’).

[viii] I have discussed the Tibetan generic features of this poem at length elsewhere. See: Perks, Matilda. “Tibetan Literary Themes in the English Poems of Chögyam Trungpa.” Resistant Hybridities: New Narratives of Exile Tibet, edited by Shelly Boil. Lexington Books, 2020.

Matilda Perks is a Ph.D. student at McGill University who studies the history of Buddhist modernism(s) and Tibetan Buddhism outside of Tibet with a focus on the life and works of Tibetan lama, Chögyam Trungpa (1940-1987), and the development of the Vajradhatu community. Among other publications, Matilda Perks is the author of “Tibetan Literary Influences in the English Poems of Chögyam Thrungpa” in Resistant Hybridities: New Narratives of Exile Tibet (Lexington Books, 2020). She was born into the Shambhala community and has been a practitioner of Buddhist meditation for 25 years.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities