ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Exhibition Review of Performing Tibetan Identities: Photographic Portraits by Nyema Droma

Chukyi Kyaping

(All images featured in this essay are courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum)

Following the British invasion of Tibet in 1903, trade agents and frontier officers took advantage of their lucrative positions to accumulate vast collections of visual and material culture (McKay 68). Though the empire’s physical presence in Tibet became untenable by 1947, Britain “resorted to reconstructing Tibet elsewhere” and these collections were subsequently used to equate territorial control with the capacity to display Tibetan culture in museums (Harris, Photography and Tibet 10). Tsering Shakya duly notes that with the absence of native voices, Tibet has “remained an anachronism [from] the age of imperialism” (22).

In Performing Tibetan Identities, Nyema Droma critically engages with the Pitt Rivers Museum’s historic collection through her photographic portraits. The exhibition successfully employs interrogative and indigenous museology to create a visual dialogue between the dynamic (con)temporary exhibition and the taxonomically static permanent displays. With native agency embedded throughout the development process, it is a powerful demonstration of the potential capacity for ethnographic museums to simultaneously learn from its past, represent the present, and imagine its future.

The photographic medium has historically functioned as a tool of imperialism to stage a wide perceived distance between the photograph’s subjects (the colonised) and its consumers (the colonisers) as a means to justify cultural and/or biological superiority (Mitchell 297). The ethnographic photographs in the Pitt Rivers collection, as with many other collections in Britain, share a compositional uniformity, which primarily served to highlight physical and cultural variation. This method directly led to the compilation of ‘ethnic types’, wherein the complexity and individuality of ethnographic subjects came to be viewed as obstacles to an institutional praxis rooted in reduction and simplification (Harris, Museum on the Roof 87).

This is reinforced by the inherent power imbalance between the photographer and those photographed—implicit in the term ‘subject.’ Photographs simultaneously embody and defy space and time, exhibiting “relentless pastness, yet timelessness” (Edwards 129). Therefore, photographic subjects and their cultural descendants are ascribed to an imagined and constructed past (133). However, instead of simply removing outdated and incorrect information, ethnographic museums stand to gain more from showing how the images have been “perceived, identified, understood and articulated” over time (137).

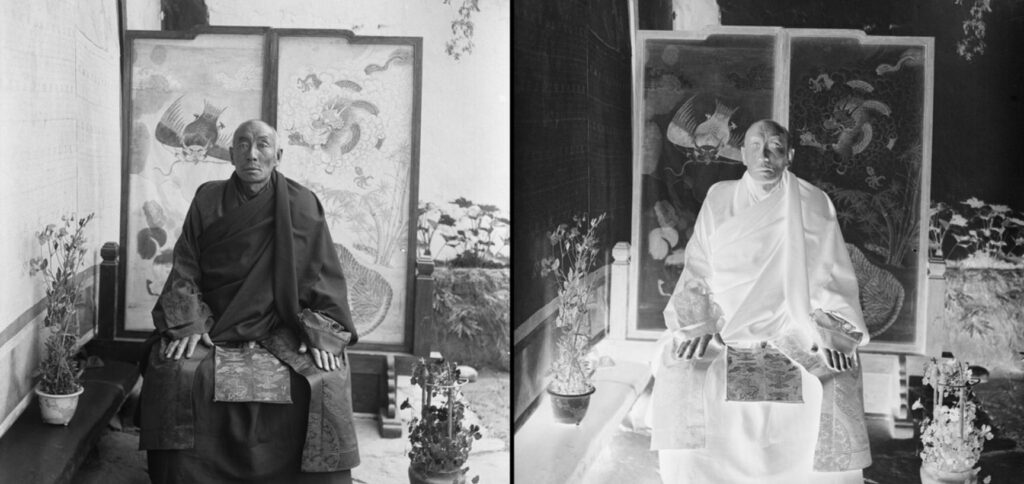

Supported by the Origins and Futures Fund (Indigenous Researchers and Artists Programme), Nyema Droma studied over 5,000 photographs taken by British officers in Tibet over the first half of the twentieth century. Particularly drawn to a set of glass plates taken in 1920s Lhasa, she immediately noticed that the positive and negative slides of each photograph almost appeared to depict different people. This observation inspired Droma to create double portraits of young Tibetans in their daily wear (polychrome) and in their ‘traditional’ clothing (monochrome), with the aim to disrupt stereotypes and the erasure of individual identity.

Thupten Kelsang argues that meaningful “engagement between Tibetan material culture and the Tibetan community” must become institutional praxis for museums to successfully decolonise their collections (130). While it is a promising start, the discourse on ‘source communities’ is still predicated on the term’s reduction of these groups to their value as knowledge repositories. Kelsang aptly contends that this leads to Tibetans acting as ‘sherpas’ for non-Tibetan scholars — referring to the Himalayan ethnic group known to guide Western tourists climbing Mount Everest (130). Therefore, the traditional role of a curator as a scholarly guardian of material culture needs to transform into a more public-facing and people-centered position.

In this vein, Clare Harris and Nyema Droma generally chose to forgo the typical boundaries which distinguish their respective roles as curator and artist-in-residence. Instead, their more equitable dynamic as co-collaborators of the exhibition has resulted in some highly innovative methods to interrogate and reanimate the museum’s contentious space. For instance, Harris and Droma took full advantage of the Great Court’s hyper-visibility with the bold suspension of eight double-sided banners above the permanent collection. Carefully selected for their relative compositional dynamism, these large portraits immediately catch the eye upon entering the museum.

The exhibition continues into the Long Gallery, where the remaining portraits are paired with a video montage of Droma interviewing her photographic subjects. Directly overlooking the Great Court, a digital screen on the upper level juxtaposes the glass plate slides with the double-sided banners. This orientation visually contextualises the temporary exhibition within the permanent photographic archive—a first for the museum.

Furthermore, the incorporation of indigenous museology serves to bolster the exhibition theme. In the Long Gallery, two pillars frame the portraits against walls of maroon and mustard yellow — a stylised take on the traditional aesthetic found in many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. In addition, Droma utilises the five primary colours found in Tibetan prayer flags as her portrait backgrounds, and the suspended banners clearly emulate the horizontal flags (lung ta).

However, they do not follow the typical colour arrangement (blue – white – red – green – yellow). The white colour is instead represented on the reverse monochromatic side of the portraits, modelled after the glass plate negatives. This deliberate break can be interpreted as a challenge to the popular perception of Tibetan culture as incompatible with change and innovation. The dual ‘performances’ in the double-sided banners also function similarly to Tibetan scroll paintings (thangka), where sacred prayers of consecration on the reverse are traditionally hidden from public view. This is echoed in the portraits depicting daily wear on the front side and the seldom worn (and arguably more sacred) Tibetan outfits on the reverse side.

Double portraits displayed in the Long Gallery

Double portraits displayed in the Long Gallery

However, the external imposition of cultural legitimacy continues to be an issue for Tibetans who prefer to be seen as global citizens. Clare Harris recalled that some visitors ultimately could not reconcile their own subconscious idea of Tibetans largely remaining incapable of cultural nuance with the cosmopolitan hyper-individuality present in the portraits — a poignant reminder of the enduring colonial gaze.

As emphasized by the title of the exhibition, Droma explores a plurality of Tibetan identities. While those depicted in the glass plates primarily held positions of religious and/or political power, Droma promotes inclusivity of individuals often demographically marginalised by notions of a ‘collective Tibetan identity,’ such as Tsering Thondrop (a trans woman) and Kesang Ball (of mixed-race heritage). Moreover, the glass plate labels anonymised and dehumanised subjects, reducing them to their societal function. In contrast, the exhibition labels include the subject’s name (in both English and Tibetan), occupation, location, and a quote discussing their identity and sense of belonging.

Sonam Tsering: “I don’t feel my Tibetan identity is defined by whether I wear traditional clothes or not.”

Karma Ermchi: “Being a Tibetan is about culture; a way of living, a language, a custom.”

Tashi Namtso: “Tibetan identity for me is about religious beliefs, ties to traditional cultures and land, and a natural warm heartedness.”

Kesang Ball: “I actually used to dis-identify myself with Tibet because of the society I lived in.”

Droma reflects on her transcultural journey from Lhasa to London and back, remarking that the “people in my photos may be others, but what I perhaps want to really portray is myself” (“Young Tibetan Photographer Nyedron”). In her own portrait, she wears Tibetan men’s clothing, to simultaneously mark the fluidity in her cultural identity as well as her gender role, as a female Tibetan photographer in a profession dominated by Western men.

Reciprocating her agency onto the individuals in her portraits, Droma challenged her subjects to experiment with ‘self-fashioning’ — in other words, the expression of cultural identity through dress and objects (“Performing Tibetan Identities”). While some corroborated popular markers of Tibetan culture, others chose to reject them. As a result, the portraits seem to ask, “which of these versions of myself fits your stereotype best?” (Harris, Museum on the Roof 251). Nyema Droma’s portraits ultimately celebrate the creative agency of young Tibetans who refuse to remain perpetual victims of their past representation.

Historically, the “Tibetan body (augmented with objects signifying Tibetanness) bore the brunt of representing the mystique of Tibet” when the land itself was inaccessible (Harris, Museum on the Roof 96). While some museums have entirely removed problematic displays in favour of more socially relevant exhibitions, many ethnographic museums seek to capitalise on their existing collections (Harris and O’Hanlon 10). Focusing on self-reflection and contextualisation, these museums argue that it is imperative to “exhibit the problem, not the solution” (Karp and Kratz 281). But the Pitt Rivers Museum’s Performing Tibetan Identities exhibition simply asks: why not both?

The results prove to be positive and fruitful for both the museum and the Tibetan community, as both strive to cement their place in the age of modernity and multiculturalism. Clare Harris and director Michael O’Hanlon argue that museums can be “therapeutic institutions and places where communities that have previously been excluded can gain recognition through representation” (12). Therefore, while the physical repatriation of Tibetan material culture may not yet be possible, this exhibition successfully highlights the potential for visual or representational repatriation.

Works Cited:

Edwards, Elizabeth. “Some Thoughts on Photographs as History.” Seeing Lhasa: British Depictions of the Tibetan Capital 1936-1947, edited by Clare Harris and Tsering Shakya, Serindia Publications, 2003, pp. 127-139.

Harris, Clare. Photography and Tibet. Reaktion Books, 2016.

– – -. The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Harris, Clare, and Michael O’Hanlon. “The Future of the Ethnographic Museum.” Anthropology Today, vol. 29, no. 1, 2013, pp. 8-12.

Karp, Ivan, and Corinne A. Kratz. “The Interrogative Museum.” Museum as Process: Translating Local and Global Knowledges, edited by Raymond Silverman, Routledge, 2015, pp. 279-298.

Kelsang, Thupten. “Object Lessons from Tibet & the Himalayas.” HIMALAYA, vol. 37, no. 2, 2017, pp. 128-130.

McKay, Alex C. “‘Truth,’ Perception, and Politics: The British Construction of an Image of Tibet.” Imagining Tibet: Perceptions, Projections, and Fantasies, edited by Thierry Dodin and Heinz Rather, Wisdom Publications, 2001, pp. 67-89.

Mitchell, Timothy. “Orientalism and the Exhibitionary Order.” Colonialism and Culture, edited by Nicholas B. Dirks, University of Michigan Press, 1992, pp. 289-317.

“Performing Tibetan Identities: Photographic Portraits by Nyema Droma.” Pitt Rivers Museum, 2018, https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/event/performing-tibetan-identities

Shakya, Tsering. “Tibet and the Occident: The Myth of Shangri-la.” Lungta, 1991, pp. 20-23, https://info-buddhism.com/Myth_of_Shangri-Ia_Tsering_Shakya.html.

“Young Tibetan Photographer Nyedron.” High Peaks Pure Earth, 30 Sep. 2018, https://highpeakspureearth.com/young-tibetan-photographer-nyedron-its-not-the- tibet-you-imagine-but-its-just-as-cool/.

Chukyi Kyaping is an art historian and recently completed her MA in Museum Studies from the School of Oriental & African Studies (SOAS).

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities