ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Editorial Introduction

Françoise Robin

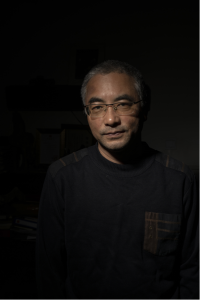

Pema Tseden, Beijing, 2019 © Gilles Sabrié

Pema Tseden (1969-2023), a cultural hero for many Tibetans, left this world on May 8, 2023. Some Tibetans made a call that May 8 should be declared as the day of Tibetan Cinema. This gives a good sense of how he had come to embody the very idea of Tibetan films. As the title of this special issue suggests, Pema Tseden was the life tree of Tibetan cinema in Tibet, the People’s Republic of China, and beyond. He braved obstacles, and there were many considering the subaltern or minoritized position of Tibetans in Tibet and the suspicion with which the Chinese authorities treat Tibetans who claim their own collective space and voice. He managed to uncompromisingly establish Tibetan cinema and reach the best of the world film festivals. He was appreciated and belonged to the inner circles of art cinema worldwide despite his limited English. His networks were wide, and he seemed to know everybody: his fellow Tibetans of course, both in Tibet proper and in exile, besides the Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Western fans of films and literature.

Given Yeshe’s mission to provide a platform for contemporary Tibetan literature and art in the wider sense, it is no surprise that articles pertaining to Pema Tseden and his works have already appeared in the journal. Yeshe, for instance, published an autobiographical essay about Pema’s childhood, seen through three pictures. Yeshe also published an interview that Pema gave in February 2019 at the Asian Cinema International Film Festival (FICA) (France), the longest-running Asian film festival in Europe, which bestowed three times – a record – the highest prize to Pema for Tharlo in 2019, Jinpa in 2020, and Snow Leopard in 2024. Clemence Henry wrote for Yeshe an essay analysing modern objects and animals in Pema’s films, mainly in Balloon, subsequently delving into religious messages in his movies. Lastly, soon after Pema’s demise, Tenzing Sonam, the well-established and widely acknowledged founder of Tibetan cinema in exile, on the other side of the Himalayas, wrote a moving tribute for his colleague recalling the late filmmaker’s cinematographic legacy and underscoring his efforts of forging a pan-Tibetan cinema. Pema was a supporter of Yeshe, as he had wholeheartedly agreed to be a member of its advisory board.

To those readers unfamiliar with Pema Tseden’s life, we refer Dhondup T. Rekjong’s valuable biography of the late filmmaker on the equally valuable “Treasury of Lives” website (Dhondup T. Rekjong 2023). It is well documented, with a profuse bibliography. With this special issue of Yeshe, we are hoping to bring to light new, lesser commented or known aspects of Pema’s extremely rich and diverse but alas short life, and to highlight the many roles he endorsed, living in fact many lives in one.

If Pema’s death is a collective loss to his community, it is an unfathomable personal loss to his family and thus we begin the first section of this issue with a contribution by Jigme Trinley, his only child. Jigme, who has pursued in the steps of his father and is becoming an important filmmaker in his own right, was kind enough to let us translate the three notes he wrote to his father on the 49th day of Pema’s passing away, a crucial moment for Tibetan Buddhists, as the namshe of the deceased is supposed to ‘migrate’ to his or her next life on that day. Jigme talks to his father as if they were still together, sipping coffee in front of the Potala, and reminiscing about his childhood with a father who, he says, could be as fierce as a wild yak. This may surprise those who remember an ever-calm, smiling, quiet person. But in fact, for Pema to succeed against all odds in his unlikely dream, as he did, to establish Tibetan cinema in today’s People’s Republic of China, he had to be brave and determined like a wild yak. Totally devoid of aggressiveness, anger or resentment, he was driven by a stubborn artistic spirit combined with a deep attachment to his people, his culture, his language, whom he sought to present in his films.

The second section of this issue, “Pema Tseden, the Friend and Mentor,” brings the voice of five of his friends: Gangzhun (Sangye Gyatso), the ever-faithful producer friend, shares in exclusivity one chapter of the forthcoming biography of Pema he decided to write immediately after his demise. Gangzhun recalls how in the early 2000s Pema took the firm decision to embrace cinema. A six-part tribute by Lung Rinchen (aka Longrenqin), another childhood friend of Pema, provides an opportunity to discover lesser-known facts and projects that enriches our understanding of Pema Tseden the writer and Pema Tseden the filmmaker. Lung Rinchen reveals that Pema had planned from early in his career to adapt to film a short story of Dhondrup Gyal (1953-1985), the famous Tibetan writer, innovator, and teacher. A piece by Chen Daqing, a Chinese artist living between the USA and China, reviews Pema’s almost entire filmography and underscores the simplicity, sincerity, and dignity of Pema. Having had the privilege of knowing Pema for two decades, I recall in my essay the important moments shared with him, including the time we spent on some film locations, complementing it with numerous pictures. In the last feature in this section, we see Pema Tseden as a mentor through the moving words of Tseten Tashi, who performed in Snow Leopard (2023). The actor recalls the filmmaker’s kindness and perfectionism. He provides us with a privileged glimpse into a crucial role that Pema constantly played since his first movie: that of a generous mentor to the younger generation.

Pema Tseden started his public career as a short story writer. The third section thus includes two essays highlighting his engagement with literature. Michael Monhart, who had previously translated some of Pema’s stories and met him on several occasions, elaborates upon the element of silence in Pema’s fiction. (Ironically, Pema’s voice has been silenced by his untimely demise, and he was indeed a quiet person.) Michael discusses the slow-motion films-like deliberate silences and minimalism in terms of events that unfold in Pema’s short stories, arguing that it should be interpreted as giving free rein to the reader’s imagination, as we are generously invited to an “imaginal space” created by Pema so as to explore our inner reality more deeply. Erin Burke also contributes to enriching our reading of Pema’s fiction through her critical analysis of the short story “Orgyan’s Teeth” (2012). She demonstrates how Pema Tseden’s exploration of faith and doubt in the modern era can be articulated to address issues of self-determination and identity.

The fourth section of this issue is dedicated to yet another role of Pema Tseden, that of translator: throughout his life, Pema not only made films and wrote fiction but also translated from Tibetan into Chinese works ranging from fiction to Buddhist writings. Patricia Schiaffini-Vedani’s paper sheds light on how, through translation, Pema also contributed to introducing Tibetan literature and rich culture to a Chinese readership, or even to Tibetans who, brought up in contemporary China, have been deprived of a full fledge education in their own language. P. Schiaffini-Vedani points to the courage that prevailed in the choice of some short stories that Pema Tseden translated.

Pema Tseden acquired worldwide fame (he may have been the only Tibetan whose obituary appeared in The Economist and the New York Times) for his role as the founder of Tibetan cinema in the People’s Republic of China. In fact, a valuable Tibetan cinema had emerged much earlier in exile under the guidance of Tenzing Sonam, but the scale at which it flourished in PRC with Pema’s ingenuity is unprecedented. Section five, “The Filmmaker I,” precisely comments and enriches our understanding of Pema’s filmography. Chris Berry, a leading scholar on Chinese contemporary cinema who analysed the usage of road in Pema Tseden’s cinema (Berry 2016), offers a hybrid, part-tribute, part-essay contribution that suggests a two-phase division of Pema’s filmography. Instead of considering Tharlo (2015) as the turning point in his career, Berry posits that it is with Jinpa, Balloon, and later Snow Leopard that Pema’s films explored a new path, that of the inner life. Jamyang Phuntsok, an exile filmmaker, reflects upon Pema’s “subjective truth,” and claims that, contrasting with failed outsiders’ attempts at rendering Tibet on screen, Pema Tseden’s early films are informed by his Tibetan subjectivity and sincerity, while his later films reveal the tragedy of changes imposed from above. He then goes on to discuss the meaning and value of close-up shots and slow-motion editing that are typical of Pema’s cinematographic style. By creating distance and opacity, says Jamyang Phuntsok, the audience is allowed to explore their inner world as well as that of the characters. Tashi Nyima, after recalling the impact and importance of Pema Tseden’s cinema, goes on arguing that Pema’s early literary works contributed to shaping his filmmaking career. Xu Feng, a professor of cinema in China and long-time friend of Pema Tseden, comments upon the evolution of Pema’s cinema. He argues that it developed over the years from being documentary realist to being spiritual realist, reflecting Pema’s own spiritual path, informed by Buddhism.

Section six, “The Filmmaker 2” offers reviews: three are by well-established Tibetan intellectuals from Tibet proper—Chamtruk, a young cinema scholar and specialist of Tibetan literature, and Lhashem Gyal, a renowned writer, and Datsang Palkhar Gyal, a film critic. These three reviews were published conjointly in Tibet proper, in the main Qinghai-based Tibetophone journal (Qinghai News – Tibetan edition) in 2020, after the release of Balloon. It is rare for Tibetan language newspapers to dedicate several pages to film reviews, and the fact that three articles were published together, each offering their reading of Balloon, is an indication of how established Pema Tseden had become. We include them with the hope that audience in the western world may be interested in this opportunity of rare access to film reviews from inside Tibet. Chamtruk’s review elaborates on the elements of intertextuality that create a tradition and permeates his films. He also comments on the film’s complex and condensed narrative style, with its fragmented characters and non-linear plots. Lhashem Gyal underscores the affinity which Tibetan audience feels for Pema Tseden’s representational choices of Tibetan life in Balloon. He also appreciates how literature and cinema complement each other in Pema’s works. Datsang Palkhar Gyal’s “An Elucidation from Outside and Inside” reflects upon four types of fundamental changes affecting Tibetan society that Pema Tseden manages to convey in his film: changes in women, changes in times, changes in species (or humanity), and changes in film. This section ends with a translation of Baima Nazhen’s (Pema Nordrön) essay on Tharlo (2015), a film she refers to in her poem also featured in the last section of this issue of Yeshe. Her essay is a personal reflection about the film and offers a glimpse into how, in her case, it acted as a catalyser to grasp social changes affecting Tibet and Tibetans.

A lesser-known aspect of Pema Tseden’s life in cinema is revealed in the seventh part of this issue: Brigitte Duzan, who runs a reference website on Chinese cinema and Chinese short stories and is herself a translator, introduces us to the growing role of Pema as a producer and art director, nurturing not only emerging talents in Tibetan cinema but also young Chinese filmmakers.

True to one of Yeshe’s commitments, that of bringing new Tibetan literary and artistic creations to a wider public, the last section consists of poems dedicated to Pema Tseden. Most were written on the day of Pema’s passing, in a state of shock and disbelief. These poetic tributes by Ré Kangling, Kyabchen Dedrol, Mukpo, Nakpo, Gar Akyung, and Baima Nazhen (Pema Nordrön), many of whom are established poets, conjure up their respective memories of Pema Tseden in their own way with heightened sensitivity and rich imagery in the poems. These poetry tributes to Pema underscore how his life inspire Tibetans, how much he means to Tibetans, and how the loss of his life is tragic for them. Gangzhun, who already features as Pema’s biographer in section two, closes the last section with a long eulogy he wrote on the 49th day of Pema’s death, contrasting the beauty of the late spring and early summer in Tibet, with the sadness of the circumstances in which he wrote this piece.

This special edition of Yeshe is a combination of original pieces and English translations of previously published material. We thank both the authors of the original pieces, who have contributed to enriching our knowledge and analysis of Pema’s rich life and legacy and the poets who gave us the permission to translate their works. It is deeply meaningful to hear the voice of Tibetans, who have lost an irreplaceable ally and representative, and to Chinese friends who knew him well. This special issue could not have been possible without the help of many translators, who eagerly contributed to making the Tibetan and Chinese originals available to an English-language readership. Stanzin Lhaskyabs, Duan Wei, Dorji Tsering, Tsering Wangdue, Kalsang Tashi, Patricia Schiaffini-Vedani, Wu Lan, as well as our distinguished poetry translators: Lauran Hartley, Norwu Amchok, Palden Gyal, Riga Shakya, and Patricia again, are more than deserving of our thanks. We also express our appreciation to Lekey Leidecker, Yeshe’s poetry editor, contributed to the selection of poems presented in this special issue. Last, we wish to express our gratitude to Chris Peacock, one of Yeshe’s editor, who first suggested that Yeshe brings out a Pema Tseden special issue.

I wish to associate Pema’s close assistant Tsemdo, as well as the young filmmaker and collaborator Khashem Gyal, to the elaboration of this special issue. Hoshi Izumi (Chime-la), my Japanese twin, Kuranishi, as well as Jean-Marc Therouanne, the founder and director of Vesoul FICA festival, Gilles Sabrié, Olivier Adam, Anne-Sophie Lehec, and Flora Lichaa kindly let us use their photographs and illustrations, for which we thank them sincerely.

Lowell Cook was kind enough to review my translation of a poem. A great ‘thukjeche’ is also owed to the anonymous peer-reviewers who provided feedback on the essays that were submitted to us, as well as the anonymous sponsor of this special issue.

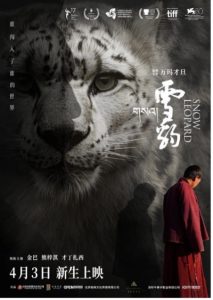

We are also very grateful to Tenzin Tendhar for the cover illustration. He managed to capture elegantly and soberly Pema’s film career through people and objects. In Tenzin’s art piece, Pema is shown with his back turned on us, echoing by coincidence an expression to be found in Baima Nazhen’s (Pema Nordrön) poem “Rainbow” in this issue. But Pema’s face is bathed in light, which can be interpreted variously. This could be the light of peace, emanating from his noble deeds, illuminating his path on his journey to the other world after he lived a life mentoring and endlessly inspiring his next generation. Indeed, his son Jigme said on the occasion of the release of Snow Leopard in the PRC, on 3 April 2024: “For those of us who follow in my father’s footsteps: We will take it slowly, one step at a time.”[1] Tenzin’s illustration reiterates the poster of Snow Leopard, with its black-and-white aesthetic, and touches of red, a combination found in posters Pema’s previous film.

The release poster of Snow Leopard

Last, let me thank the two co-founders and co-editors of Yeshe, Shelly Bhoil and Patricia Schiaffini-Vedani, who suggested and made this special issue possible. Working with them was inspiring and their creative energy, availability as well as their rigour has been inspirational throughout. Their dedication and willingness to bring out this creative online journal, despite busy schedules and various hindrances, are truly remarkable.

This issue is dedicated to the memory of our friend Pema Tseden, and to all Tibetans who contribute to keeping the spirit alive.

Works cited

Berry, Chris. “Pema Tseden and the Tibetan Road Movie: Space and Identity Beyond the ‘Minority Nationality Film,’” Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 10(2), pp. 89–105, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508061.2016.1167334

Dhondup T Rekjong, “Pema Tseden,” Treasury of Lives, accessed May 04, 2024, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Pema-Tseden/13816.

Notes

[1] https://www.shine.cn/feature/entertainment/2403259561/

Françoise Robin is a Professor of Tibetan language and literature at Inalco. She specializes in Tibetan contemporary literature and cinema, as well as the emergence of feminism in Tibet. She met Pema Tseden as early as 2002 in Xining, when doing fieldwork about young promising writers. She accompanied him at some festivals as a translator and subtitled most of his films into French. She has also translated a selection of Pema Tseden’s short stories (Neige, 2016), along with Brigitte Duzan. She is the guest editor of the present volume of Yeshe.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities