ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

A Conversation with Tenzing Rigdol about Art and Education

Sarah Magnatta

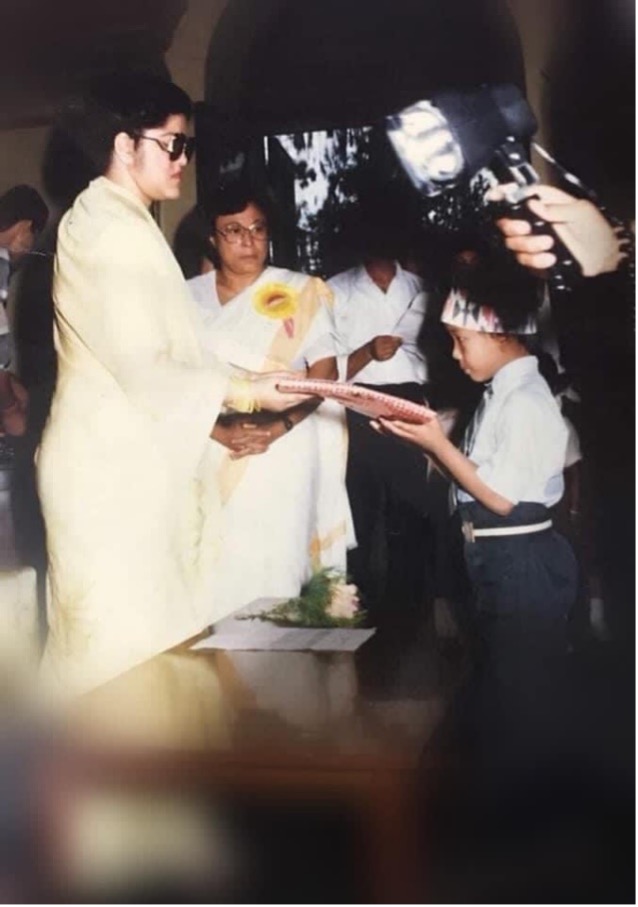

On May 3, 2022, Tenzing Rigdol was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Colorado Denver, his alma mater, becoming the first Tibetan artist to receive this recognition from a U.S. institution. I recently sat down with Rigdol and asked him to reflect upon the award, his experiences in education, and two decades as a working artist.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Tenzing Rigdol is awarded his honorary doctorate from the University of Colorado Denver on May 3, 2022. Image courtesy of CU Denver Advancement.

Sarah Magnatta: Thanks so much for chatting today. First, congratulations on the honorary doctorate! You are in great company, by the way, in terms of other Tibetans who have received honorary doctorates from U.S. institutions: they include Tenzin Gyatso (the Fourteenth Dalai Lama) and Jetsun Pema (former Director of the Tibetan Children’s Village). To my knowledge, though, you are the first Tibetan artist to receive an honorary doctorate from a U.S. institution. Can you speak a bit about your experience as a student at CU Denver in the early 2000s? Do any particular moments stand out now, almost twenty years later?

Tenzing Rigdol: I remember I always wanted to paint. That was the thing. But, sometimes it was difficult because I was an international student and we had a rental apartment but no studio. So, I just used to paint wherever. One time, I was painting on campus in a smoking area where the art students would smoke. A professor came out to smoke too, and then he sees me and says, “What are you doing here?” “I’m sorry I’m painting….please let me paint a bit more.” And he said, “No, no, you can’t” and I said okay. So, I took the easel painting, and I didn’t know where to go, so I just put the easel and everything right in the corridor of the building and started painting. And again, the professor comes out and sees me and says, “What are you doing here? You can’t paint here.” I said, “This isn’t your classroom!” After 15-20 minutes he brought a dean back with him. The dean said, “What are you doing, Tenzing!” And I said I wanted to paint and there is no space to paint, and he said, “Don’t worry, don’t worry.” He looked around and he said, “Come tomorrow or the day after tomorrow and I’ll figure out something.” And the next day, he brought me to an empty classroom—a huge classroom—he gave me the keys and said, “This is your studio.”

Sarah Magnatta: Wow! What a story!

Tenzing Rigdol: I had the biggest studio, and access to the key, and university security was also told that I would be painting there.

Sarah Magnatta: That sounds like an incredibly supportive gesture. You took some time away from CU Denver while you were a student to study painting in Nepal. Can you tell us a bit about that time period?

Tenzing Rigdol: While I was studying in Colorado, I had a painting professor, Professor John Hall, and I really wanted to take his class. He was a very popular teacher. I got into his class. So, one day my uncle sends me a book about Tibetan thangka paintings, kind of a catalog of Tibetan paintings. I proudly took it to class to show off something very unique—there was no text, it was all basically a catalog. The professor looked at it, his eyes widened, and he said, “What is this!?” I said thangka painting. “Oh wow!” he said. He opened the next page and asked, “What is this?!” I said thangka painting. “But this looks different, right?” he said. I said, “All I know is that these are all thangka paintings!” And he said, “But you don’t know anything about the different meanings?” I said I really don’t know. So, that triggered me. That’s why I went to Nepal! I was looking for teachers who could teach me not just how to paint a thangka but could tell me the stories and meanings that John Hall was asking about.

So, I went to Nepal. While I was there, I saw a note on a board about a Tibetan thangka school with ninth-generation thangka painters Phenpo Tendhar and Tenzing Gawa. So, I went and knocked and said I’m a student in the U.S. studying art. It’s not that I want to be a thangka painter, but I want to do research for my own study of art. And Phenpo Tendhar said, “I’m a tough teacher, you will have to get up early to come here at five in the morning!” And I agreed and then he said, “Okay, come and I will teach you.”

Sarah Magnatta: So, this was before you finished your degrees at CU Denver.

Tenzing Rigdol: Yeah, I was still a university student, but I took a break in between to do the research on thangka. That’s how thangka painting was introduced to me, by Phenpo Tendhar and Tenzing Gawa. Because John Hall at CU Denver pushed me and asked me difficult questions. Sometimes you are always asking yourself the same questions, but with John, coming from someone I admired, and it was difficult to get in his class, and difficult to get through his class—when he asked those questions, it became serious. He said, “Why aren’t you asking these questions? What are these things? How are they made?” And I had always been surrounded by those things (thangka) and didn’t know.

Sarah Magnatta: It sounds like your education in Nepal nicely complemented the work you were doing in school in Colorado.

Tenzing Rigdol: Sometimes I think it’s important to remove oneself from whatever environment you’re in. If you’re in a city, go to a village. If you are in a village, go to a city. Just to give the same patterns in your mind a rest. It helps to look through different perspectives.

Sarah Magnatta: When you returned to CU Denver in 2019 for your solo exhibition My World Is in Your Blind Spot, you were exhibiting in the same space that your artwork was shown as a student, though now, of course, you have work hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among many other international collections. Has your practice changed in terms of how you approach a new work?

My World Is in Your Blind Spot, Emmanuel Art Gallery, University of Colorado Denver, March-June 2019. Photograph by Sarah Magnatta.

Tenzing Rigdol: I am getting some clarity. In a way, now I’m beginning to look more clearly at the process, the very process of questioning the process itself! When you are studying art, it is all about measuring and comparing, or observing or adopting a model, or adopting a cycle or process. And then slowly you integrate the process for a long time. That process can be skillfully flexing your hand, or seeing how your mind can observe things. And then slowly you are asking deeper questions. You take aid from philosophical sides, and also see how they are positioning the question—how they create meaning out of the question and answer system. I’m trying to see how this relates to art as an expression. And so on! But also, at that time, I was doing more research, art was more “there.” It was less about exhibitions. It was less about how others would look at it. It was mostly learning.

Sarah Magnatta: I like what you said about not yet worrying about how the work was going to be received by the audience.

Tenzing Rigdol: Between you and your brush, nothing should interrupt!

Sarah Magnatta: This leads me to a question about the reception of your work and audience connections. The current Dean of the College of Arts and Media at CU Denver, Laurence Kaptain, said during the award recognition process, “Thank you to Tenzing Rigdol for demonstrating the essential linkages that illuminate the pathways of both courage and consciousness.” His statement highlights issues of social justice in your work, particularly those images or installations that may be viewed as political or dangerous, for example, Our Land, Our People, wherein you risked quite a bit to bring Tibetan soil across two borders into India. Because of this, you have sometimes been described as an activist in addition to an artist (although I know you have questioned that term before). Can you tell us how you imagine your artwork being received by various audiences? Do you feel pressure to do “political” work, or, perhaps, work that may be seen to speak for or to specific causes?

Tenzing Rigdol. Our Land, Our People, October 26-28, 2011. Site-specific installation, soil, silk brocade on wooden platform, 43’ x 43’ (13.1 x 13.1 meters) platform area. Dharamsala, India. Image courtesy of Tenzing Rigdol and Rossi & Rossi.

Tenzing Rigdol: As an artist, first, you respond to a problem. Okay, Tibet has this problem. And you say why, why, why. You bring the literature out, the history, you study that too. Okay. And then you see actually it’s not just Tibet. You look around…it’s happening everywhere in different structures, now you pay attention to the same political thing, we call it politics, or conflict, or disagreement, or any name we use. But then you’re also paying closer attention to that kind of experience. And then you see it is all interrelated to one’s ability or will either towards a solution or towards being stuck in memory. So how do we untangle it? Then what kind of discussion do we have? It can be applied to Palestine, applied to Kashmir, applied to Hong Kong, to Native Americans, Mongolia, North Korea, everyone! It might look different, but there are elements that are universal. And can that be the subject of art? I don’t know, but we can ask.

Sarah Magnatta: That’s a good question. There is a universality to your work that goes beyond issues pertaining to Tibetan political discourse. Along those lines, then, what do you think of the term that we so often use when describing your work: “Contemporary Tibetan Art?”

Tenzing Rigdol: Do we want to go with the definition of geography being the central theme? Or some would say culture being the central theme? Or should the issue dictate the theme? Or subject matter? I think all the terms—forget even “Contemporary Tibetan,” like “Asian”? All of them! We need to have a discussion like this if we want to peel off all of these approaches. So, is there pressure to do political art? No, not really, because I want to find one lens that’s a little bit powerful to focus on the same subject matter, the same question. And then see if I can improve the lens, and on and on, refining the lenses….and then one can move into one’s own practice.

Panel at the Emmanuel Art Gallery at the University of Colorado Denver on May 4, 2022 to mark the occasion of Rigdol’s award. From left to right: University of Denver assistant professor Sarah Magnatta, University of Colorado Denver assistant professor Yang Wang, Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Kurt Behrendt, and artist Tenzing Rigdol. Rigdol’s work can be seen in the background. Photograph courtesy of Danielle Stephens.

Sarah Magnatta: This award seems like an appropriate moment to look back and reflect on the past twenty years of your career. During the panel discussion that corresponded with your award, we showed several artworks spanning this period; can you tell us which ones stand out for you and for what reasons?

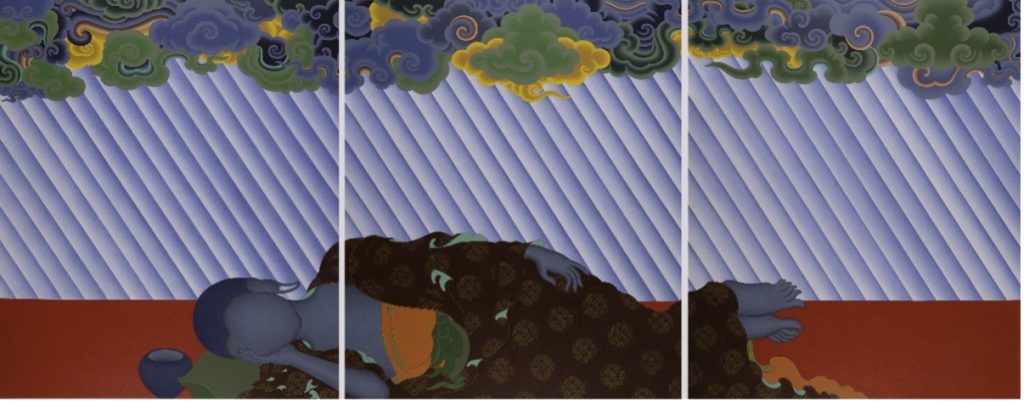

Tenzing Rigdol: I was walking in Delhi one time, it was a crazy hot summer. Really burning summer. And then you walk out right there, there were three or four beggars just sleeping with a begging bowl. And right next to them, a big five-star hotel. I thought it was such an interesting juxtaposition. So, I did this one painting based on that called Landscape, with the Buddha sleeping. It’s an acrylic painting with the sky split. So sometimes artwork happens like this. From that feeling, you have this image, but in the end, you can also twist and turn it and make the image in a more particular way. So, I added fire to the cloth, and immediately it particularized it [here, Rigdol is referencing the self-immolations of Tibetans and his ongoing use of flames in much of his work].

Tenzing Rigdol, Landscape, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 178cm x 453 cm (70” x 178 ½”) Image courtesy of Tenzing Rigdol and Rossi & Rossi.

Sarah Magnatta: That’s so interesting; I have seen that image several times and never knew about that origin story.

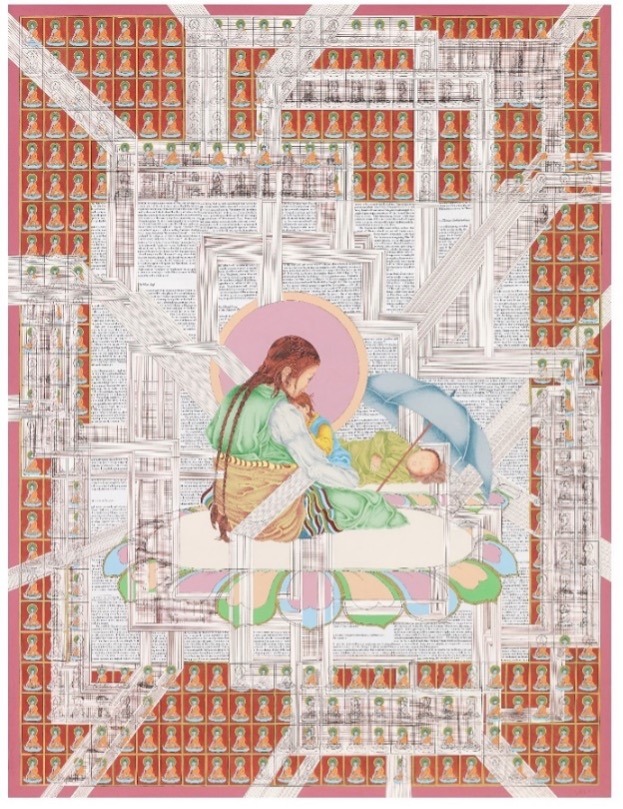

Tenzing Rigdol: Sometimes you put two images juxtaposed—you know, it’s like if you tell an actor to feel sadness and happiness at the same time, see if we can merge the two. And I think in that way it worked. There was one (artwork) that started when I saw a picture of a road builder. And it was a mother with a child and umbrella, and when I first saw the picture—my mother also had two kids you know, so it looked like maybe it could be my mother at her age. And it looked like me or my brother, so there’s also this personal connection there. But I don’t talk about or say, like with the beggar image, how it started…it’s too personal.

Tenzing Rigdol, Genesis: Introduction to the Beginning of All, 2017, Acrylic and gold on treated paper, 132 x 99 cm (52 x 39 in). Image courtesy of Tenzing Rigdol and Rossi & Rossi.

Sarah Magnatta: I see. So part of it—the starting point—maybe it’s too personal so you have to let that part go, in a way.

Tenzing Rigdol: Yeah sometimes, in a way, it is like sometimes it can just be turned into the political, but it can be particular or universal. But it’s always very organic.

Sarah Magnatta: Do you have any other thoughts you would like to share regarding the award or your reflections on this mile marker?

Tenzing Rigdol: Regarding the award, I have been thinking, how should I understand it? And then I was thinking, mostly it is really about all the schools, you know. If the teachers are not there, the art is not there. Whether it’s the Tibetan Children’s Village school or the thangka academy… all the way up to my university professors and friends. If artists have been able to do something, then it is because of all these teachers. So, my teachers, everybody from kindergarten to now, I recognize in this award because the best part of me came from them.

Sarah Magnatta: That’s really wonderful—that’s a really beautiful way of thinking about it.

Tenzing Rigdol: So, I’m still a student!

Tenzing Rigdol as a child while receiving an award for his artwork from the Queen of Nepal, Aishwarya Rajya Lakshmi Devi (date unknown). Image courtesy of Tenzing Rigdol.

Sarah Magnatta is an assistant professor of art history at the University of Denver specializing in global contemporary art and museum studies. She previously worked at the Denver Art Museum and has independently curated several exhibitions, including Tenzing Rigdol’s first solo U.S. exhibition, My World Is in Your Blind Spot at the Emmanuel Gallery in Denver and the Tibet House in New York City in 2019. She is currently on the Museum Committee of the College Art Association.

Tenzing Rigdol was born in Nepal in 1982 to parents who fled Tibet in the 1960s. He studied painting, drawing, and art history at the University of Colorado Denver in the early 2000s, earning both a BFA and BA. He studied traditional Tibetan sand painting and butter sculpture at the Shekar Chorten Monastery and traditional thangka painting at the Tibetan Thangka Art School, both in Kathmandu. Rigdol’s work is the first by a contemporary Tibetan artist to be acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City for its permanent collection. He received his honorary doctorate from CU Denver in 2022.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities