ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Three Photographs and the Days of My Youth

Pema Tseden

(Translated from Chinese by Brantley Collins)

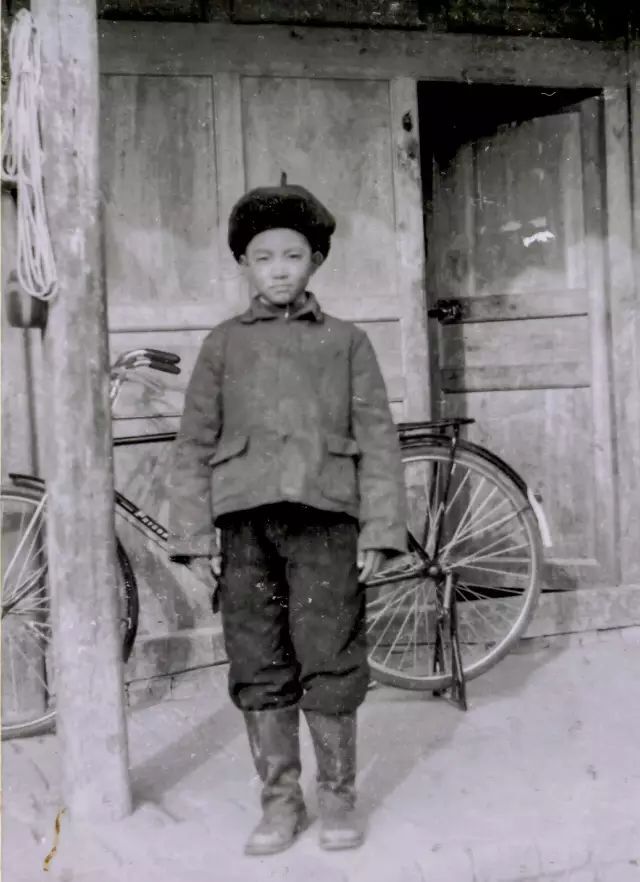

This is the first photo of me ever taken. It was taken when I was 11 or 12.

At that time, having your picture taken was a very difficult thing and a rare luxury. I remember there was a bespectacled middle-aged Han Chinese man wearing a camera around his neck who would wander around our village every year, looking for opportunities to persuade people to take a picture as a memento. In those days no one had much money, so when they saw the photographer coming, parents would make every effort to hide as far away as possible. They were afraid that their children, not understanding the situation, would make a scene and cause them to lose face. I think the reason I was able to take this picture must have been my paternal grandfather. He was convinced that I was the reincarnation of his uncle. His uncle was a Tibetan Buddhist monk of the Nyingma school who owned many volumes of sutras and was rather well educated. My grandfather said that it was thanks to his uncle that he could recite some Buddhist scriptures and understood some Nyingma rituals, and he was grateful for this. Supposedly, when I was very young, I spoke about some things that had to do with his uncle, and that was why my grandfather was so sure that I was the reincarnation of his uncle. At that time my grandfather was the authority figure in our family, and he made almost every decision. So I think it was because my grandfather was partial to me that I was able to take this photo. The clothes I’m wearing in the photo are clothes that in those days could only be taken out and worn during Losar. The boots in particular I wore for many years. I remember that the first time I put them on, they were so big I could only drag them around, and I could only wear them by stuffing them with a lot of padding to prevent blisters on my feet. As I grew older, the boots began to fit my feet better, and they were so comfortable that I wore them until they were completely worn out, and even then I didn’t want to take them off. I didn’t realize until I was a bit older that the reason I was given large boots was just so I could wear them for a few extra years. The cotton-padded hat on my head was the same, and it accompanied me through many cold winters.

Taking a photo was actually just a momentary thrill; it was over with a quick “ka-cha.” I was left unsatisfied and would linger in front of the camera, unwilling to leave, and I had to be forcefully pulled away. Afterward was just an endless wait. In those days we had to wait at least two or three months before the photographer brought the photo to your house in a paper sleeve made of old newspapers. From then on, the photo would be displayed in a prominent place on the wall of your living room as it slowly yellowed with age.

The background of the photo is a cabin that my family owned. I have many happy memories of the time I spent in that cabin. Sadly, it was later torn down and replaced with a brick-and-wood house.

Behind me is a bicycle. I remember it was a Flying Pigeon brand bicycle, and at the time it was my family’s most valuable possession. Once when I was home alone I took it to the threshing ground to ride it, but disaster ensued: I was left bruised and battered, and I was sore for several days.

I was probably in third grade when this picture was taken. Back then, our school’s classrooms were all old and dilapidated, and few in number. One summer, classes were held on the second-floor balcony of our village temple; it was pleasing to enjoy the scenery while we had class. One summer a team of film projectionists came and showed a movie in the main hall of our temple. It was a long, two-part romantic film called Youth in Our Village. I had no idea what romance was, and it left me with a lot of beautiful daydreams. Afterward I thought of that movie often.

About two years after this picture was taken, I graduated from elementary school, and I left my village to attend middle school in the county seat. That was really my first time leaving home. By then I had learned to ride the bicycle, and my family gave it to me to keep.

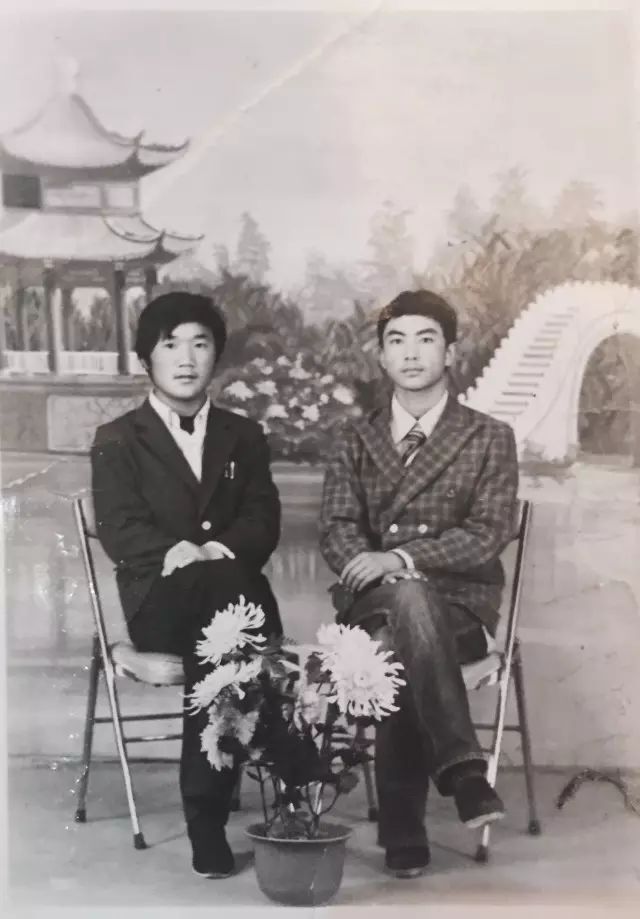

The second photograph was taken after I had graduated from middle school and tested into our prefecture’s secondary-level teacher-training school, probably about the time I was set to graduate. At that time taking a photo was still not as easy and casual a matter as it is now. It was only with very close friends that we would occasionally take just one photo as a memento.

The person on the left was a good friend of mine, one grade behind me. Now he is one of the People’s Police, and we’re still in touch. I often have a chance to see him when I visit my hometown, and he even helps me handle things like my ID card and passport.

I can’t remember the specific occasion for this photo. Maybe it was that I had just gotten this new suit. At that time something called “Panama Fabric” was in style; I don’t know why it was called that. We couldn’t afford suits off the shelf, so everyone went to a tailor to have one custom-made, and that’s how I got this suit. I even wore a tie for this picture; I must have borrowed it from the photography studio.

At that time I had a taste for trendy things, and these clothes were an expression of that inclination. Another example was that I liked listening to popular music. I had a cassette recorder about the size of a brick of coal, so it was called a “briquette,” and it counted as a luxury. That, too, was bought for me by my grandfather. Since I couldn’t afford to buy music on cassettes, I just bought blank ones and made copies at the music shop for one yuan each. Teresa Teng’s songs were just becoming popular. My teacher called it “decadent music,” but I had no idea what “decadent” meant and just thought she sounded wonderful.

In those days, there were still movie theaters in our prefecture, and the theaters still showed movies. One time, our school organized a group to go see a movie called Life. I thought Song Qiaozhen was such a beautiful girl.

After graduating from the teacher training school, I returned home to work as an elementary school teacher. I can picture the scene the first time I got paid. I had ninety-nine yuan and was thinking that was just one yuan short of a hundred—a lot of money! I took that money to the county seat to buy some books and also some things for my grandfather. I remember buying an exquisite edition of Dream of the Red Chamber published by People’s Literature Publishing House, and I read it from cover to cover. It drew me in deeply, and I thought it was such a great novel. I’ve kept that copy all these years, even if it’s a little worse for wear.

Back then, elementary school teachers had to teach everything: Mandarin, Tibetan, mathematics, ideology and morality, music…and the students were so cute. Their living conditions and learning conditions were much better than mine had been.

After working as a teacher for three years, I was ready for a change. My only way forward was to test into a university. When I’d been assigned to my post, I’d signed a contract with the Bureau of Education requiring me to stay on for six years. When I mentioned my interest in taking the university admission test, I had to write a statement promising to give up my position if I failed to pass the test. At the time this decision caused a bit of a stir; I was told that I was acting rashly and failing to consider the consequences. To have an “iron rice bowl” like mine was no easy feat. Many people felt that to have such an official position meant that you would never have any worries.

Afterward, I successfully tested into the Northwest University for Nationalities, with Tibetan language and literature as my major. My university, in Lanzhou, Gansu Province, was a beautiful school with some very distinctive buildings designed by Soviet architects.

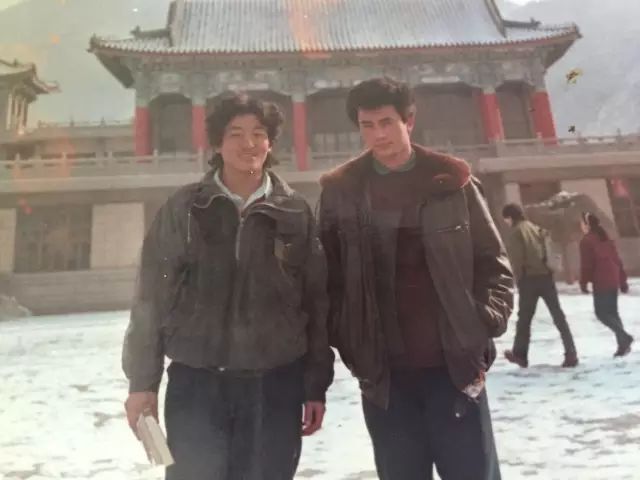

The third photograph was taken during my first winter at the university. That was a very cold day, and it had snowed heavily. In the background is the school’s auditorium. The school showed movies every weekend, and I saw many films in that building. It was also where our orientation and graduation ceremonies were held.

The person with me in the photo was a classmate from my prefecture. As the only students in the class from our prefecture, we felt a natural kinship. Everyone was so enthusiastic in those days; we all enjoyed literature. In my first semester, I published my maiden story, “Man and Dog,” in Tibetan Literature magazine, a provincial-level literary journal. It was a big deal in our department and gave me a sense of accomplishment. This classmate of mine liked writing poetry and drinking, and he sometimes got into fights—the kind caused by excessive passion. He later wrote a long poem, dedicated to a girl, that many people found very moving. He works in business now and no longer writes poetry; he’s the chairperson of a company.

The jacket I’m wearing in the photo is a leather bomber jacket. They were in fashion at the time. It was given to me by an older cousin, a performer in our local song and dance troupe. He was a baritone with a deep, resonant voice that we all envied. He had a lot of clothes, and he’d probably worn this jacket for two or three years. When I tested into university, he made a gift of it. I had it spruced up and wore it for the first two years. Then a classmate of mine took a liking to it and wanted me to give it to him, so I did. He wore it for the next two years, all the way up to graduation.

When we filmed Tharlo, I thought of that jacket. I wanted to have Tharlo end up wearing a jacket like that, so I searched everywhere for one. I asked that classmate, but he said he’d long since given it to someone back home. I even asked him to check with that person, but the person he’d given it to said it had already gotten too threadbare, and he couldn’t find it. Later I managed to find a jacket like that and had Tharlo try it on, but somehow it didn’t seem right, so I dropped it.

Like smoke, so many experiences vanish from memory without our being aware of it. It’s fortunate that we have some old photos that allow us to preserve some of those beautiful memories.

Pema Tseden is a writer and a filmmaker. Author of more than 50 short stories and novels written in both Tibetan and Chinese, his work has won the Light Rain Tibetan Literature Prize and been translated into English, French, Japanese, and German. His films include Old Dog, Tharlo, The Search, and The Silent Holy Stones. His recent film Jinpa (2018) was awarded the best screenplay in the Orizzonti program at the 75th Venice International Film Festival.

Brantley Collins graduated from San Antonio’s Trinity University in 1997. Having studied Mandarin at Trinity and National Taiwan Normal University, married a native of Shanghai, and worked in the China travel industry, he has long been fascinated by China’s rich languages and cultures. He currently maintains the website Camilla’s English Page and works as an independent language teacher and proofreader.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities