ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

The Politics of Translation: Centering the Richness of Tibetan

Language in the Anthropology of Amdo

Charlene Makley

Abstract

In this essay, I reflect on the nature and stakes of translation politics in my anthropological and historical research in Amdo as a way to reconsider asymmetric relations among Tibet scholars and their interlocutors. I draw on my most recent research project, working with a team of Tibetan co-translators to collect and translate oral history interviews on the Tenth Panchen Lama’s post-prison tours of Amdo, to offer five “reflections” on what it would mean to truly center the richness of Tibetan language in Tibetan studies research and writing practices.

Keywords: Tibet, language, translation, decolonization, collaboration

In recent years, especially since the rise of the Black Lives Matter and indigenous Land Back movements in the United States, “decolonization” has been an important rubric for calls to center native and marginalized voices and cultures in academic projects. Yet, critical theorists have long expressed skepticism at invocations of “decolonizing” as a mere metaphor for the appearance of diversity. Such theorists argue instead that decolonizing academic practices entails recognizing the ongoing legacies of colonialism as well as the potentially painful complicities of well-intentioned scholars’ research. As Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith famously put it, in her now-classic book Decolonizing Methodologies, “‘Research’ is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary” (1999, 1). Decolonizing academia for Smith and others requires long term work for structural change that would remake institutions for marginalized communities and actually de-center colonial prestige, power, and epistemologies[1].

I consider translation practices as the heart of these politics in Tibetan Studies’ past and present. Here, I offer five reflections as I rethink in this light what centering the richness of Tibetan language in my own translation practices might mean. I draw on examples from my long-term collaborative project with several Tibetan co-researchers, on oral histories of the Tenth Panchen Lama’s 1980s post-prison tours of Amdo (now part of Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan provinces in the People’s Republic of China). We have been working on this since 2016, and our team has collected and begun to transcribe and translate over hundred Tibetan-language interviews with a variety of Tibetans in Amdo and now, abroad.

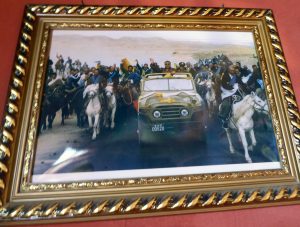

The Tenth Panchen Lama arrives in Chabcha, on the first leg of his post-prison tours of Amdo, 1980. Photo displayed at the Tenth Panchen Lama Memorial Temple, Tsekok, Amdo, 2018 (photo by author).

Reflection I: Privilege and Collaboration

Centering the richness of Tibetan language in this collaborative work highlighted the great privilege of my own position as a white American-born native speaker of English with access to graduate training in linguistic anthropology and a tenured professorship in the United States. In graduate school, I learned all sorts of abstract theories about language politics, the unequal power and prestige of world languages amid colonial institutions and nation-state standardization projects, as well as the importance of competing linguistic ideologies in shaping those relations.

But none of that training, I realized, meant anything until I entered into collaborative translation work with Tibetans. Any theory and practice of language and translation I have developed have been collaboratively created with them. That work taught me, or better, made me inhabit and recognize what many anthropologists still erase in their English-language publications: the extreme complexity, interpersonal and epistemological messiness, and differential stakes of translation. “Collaborative” here does not mean smooth or harmonious transfers of mere information. As the Native American linguist Wesley Leonard reminds us, advocating for what he calls “relational accountability,” (231) language communities do not necessarily share the same notion of collaboration, and interlocutors in academic settings are often asymmetrically positioned in terms of access to authority and resources. The terms of any such work thus need to be explicitly clarified rather than taken for granted.

Reflection II: Challenging Translation Ideologies

Centering the richness of Tibetan language entails challenging globally dominant translation ideologies, which erase the geopolitics of languages and claim the capacity to seamlessly extract and deliver content as useable information across widely different language worlds. We live in a world facilitated by the universal language utopias first widely modeled in English-only sci-fi franchises like Star Trek, or now (seemingly) manifest in AI-powered digital translation machines like Google translate.

By contrast, the linguistic anthropologist Susan Gal points out that the term “translation” in fact covers a wide variety of communication practices aimed, problematically, at comparison, commensuration, even equivocation among languages and contexts. Translation is for her a socially embedded “metasemiotic activity,” in which translators take a segment of discourse and objectify and reframe it in a different semiotic system, all while seeming to “keep something about it the same” (2015, 227). In this view, no universal language is discoverable in translation work, only a “staggering number” (236) of conversions across all levels and kinds of linguistic and semiotic forms.

Thus, to ground ourselves in the richness of Tibetan language requires attention to both the complexity of form (including non-verbal features so difficult to convert into others’ languages) and to Tibetans’ own ideologies of language and translation. As Lama Jabb (2015, 2016) and others have argued, with the intensifying modernization pressures of the 19th century Great Game and the Chinese Communist Party takeover of Tibet, Tibetan linguistic and translation ideologies have placed great value on particular traditional and contemporary genres of poetry as key mediums of Tibetanness under increasing duress. This point highlighted for me the very high stakes of the translation work we do in our Panchen Lama project.

Across such great distances of meaning and context, and as my own unspoken translation ideologies lead me to select, reframe or objectify certain things over others, I very often feel that I fail and betray the Tibetan sources even as I try to focus on rendering the complexity of Tibetan poetics in English. I did this, for example, by translating lyrics of lament songs for the Panchen Lama that were devoid of the original music; or by highlighting in my first essay an elderly monk’s kartsom (ཀ་རྩོམ་, alphabetical poem) about the Cultural Revolution, while effectively downplaying our huge corpus of oral narratives; or by deciding to give up on rendering in English the crucial meter of contemporary nine-syllable gur (མགུར་, Buddhist song) poems.

But I am also aware that in the geopolitics of translation ideologies, Tibetan and English meet as almost polar opposites. The unprecedented global dominance of English has positioned it as a universalizing language, a seemingly transparent medium of capitalist rationality, statist monoglot standards, and proper cosmopolitanism (Seargeant 2008). In Tibetan-English commensurations then, an exclusive focus on the “poetic” in Tibetan discourse, given mainstream, modernist assumptions that marginalize or exoticize things labeled “poetic,” risks ethnicizing Tibetan language as a merely local niche medium, irrelevant in larger scale contexts and debates−Tibetan language in practice is not all about poetics.

Reflection III: Translating Contexts and Stakes

There are other richnesses of Tibetan language that must be addressed in translation practice: the multilayered complexity and potential stakes of cultural, political, and historical contexts. This work on the tenth Panchen Lama’s afterlives has shown me, on so many levels, how socially and culturally embedded all language is (which is why I think of all my co-translators as my teachers). There is nothing abstract about language; it is embodied and made manifest, meaningful, and real only in and through interactions. Thus, for example, all of our translation work on Panchen Lama stories emerges through ongoing conversation and debates about competing histories and their implications, about the nature of truth and evidence, or through our own personal narratives that were elicited by the various commensurations we tried.

In this, I had to check my own ontological assumptions about ideal objectivity and embrace the specific nature of my Tibetan co-translators’ and interlocutors’ reverent relationships with the Panchen Lama. And that in turn taught me about how different the stakes are for me than for my Tibetan colleagues, several of whom continue to navigate the political dangers of escaping Tibet. For example, our conversations with a well-known dissident poet now living in exile about his relationship with the Panchen Lama unexpectedly sparked for him traumatic memories of his imprisonments at the hands of Chinese and Tibetan security officials in Amdo. And when we turned to translating his poems, he had to grapple with the political and emotional stakes of drastically scaling up his audiences (and his exposure) to transnational English speakers.

Reflection IV: The Tensions of Intra-Community Translations

We also had to address richness in Tibetan language that is potentially uncomfortable for us to navigate together because it risks drawing attention to our mutual complicities in unequal social relations: the blendings and tensions of what we could call intra-community translations. By that I mean, the complex conversions we negotiated among for example, different varieties or registers of Tibetan that are often loaded with differential evaluation and moral discourses, such as differently valued regional varieties, elite urban vs. marginalized rural dialects, monastic vs lay lexicons, or claims about “pure Tibetan speech” (བོད་སྐད་གཙང་མ་) vs “mixed speech” (སྦྲགས་སྐད་) incorporating Chinese language elements (cf. Thurston 2018).

In our work, intra-community translation politics shaped the awkwardness we often encountered in entextualizing oral Amdo speech into standardized written Tibetan. I saw this in my work with a lay male Tibetan colleague to translate the interview I did with the tenth Panchen Lama’s nephew, himself a respected lama. My colleague struggled with the dissonance of the lama’s high status, the relatively prestigious, sacred, and authoritative nature of written texts for Tibetans, and the great deference the lama was due, in contrast to the lama’s highly colloquial Amdo speech in our interview, the informal register he adopted with me, and his penchant for using Chinese loanwords.

Reflection V: The Lion and the Dog

Centering Tibetan language in our work compels me to see the complexity and messiness of translation not as inevitable failure to be erased or disavowed, but as a necessary and pervasive process to be highlighted and accounted for in and outside of our explicit scholarship−academics are not the only ones translating! Translation work is in fact pervasive and socially generative (for better or for worse); it builds social worlds and boundaries among them, including helping to create the very languages translators often presume to preexist their work as bounded entities. So, my question is: what social worlds and realities are we complicit in producing through our translation practices? We co-produce many things in our work, not the least is versions of Tibetanness and Tibetan language (and in our case, of westernness, Americanness and English language) but also power-laden social relations among translators and their interlocutors.

For example, as Susan Gal put it, “the direction and purpose of translation matter in creating boundaries” (2015, 231). Our work on Panchen Lama stories, like most of Tibetan studies, has been unidirectional; English, and the larger audiences it reaches, are the targets. Does our unidirectional translation practice thereby recreate boundaries between asymmetrically positioned languages? What counts as an extractive or exploitative translation practice versus a beneficial one? To whom? As the Panchen Lama himself famously argued in his scathing 1987 speech to the CCP Standing Committee in Beijing, translation in the other direction (e.g., into Tibetan) does not necessarily decolonize. Like western Christian missionaries’ Tibetan translations of the Bible, Chinese state Tibetan language textbooks were explicitly aimed at cultural and political assimilation of Tibetans.

Finally, in our Panchen Lama work, my control of the funding and privileged access to resources derives from long colonial histories, requiring me to rethink authorship and the nature of our collaboration such that my co-translators feel recognized and fairly compensated as expert scholars and authors in their own right. I am haunted here by Gendun Chophel’s scathing critique of the Russian scholar George Roerich, who employed him in the early 1940s to translate the Blue Annals, only to grossly undercompensate him and effectively take all the credit (cf. Bogin and Decleer 1997, Lopez 2006). In “Sad Song”, Gendun Chophel’s eleven-syllable gur poem about his unequal relationship with Roerich, he bitterly lamented that,

ཤེས་བཙོན་ཐོས་པ་ཅན་གྱི་ཉམ་ཆུང་གི་ཁ་སྟབས།།

བླུན་པོ་ནོར་རྐྱལ་ཁུར་བའི་དབང་ཤེད་ཀྱིས་བཅོམ་སྟེ།

ཆོས་མཐུན་བཀུར་སྟིའི་བཞུགས་གྲལ་གོ་ལོག་ཏུ་བསྟེབས་ནས།།

སེང་གེ་ཁྱི་ཡི་གཡོག་ཏུ་འགྱུར་ཚུལ་འདི་སྐྱོ་བ།།

(1990, 395-399, 401).

The abilities of a humble scholar, seeking only knowledge,

are crushed by the tyranny of a fool, bent under the weight of his wealth.

The proper hierarchy has been reversed;

How sad that the lion is made servant to the dog (Lopez, trans., 2006, 32-3).

Works Cited

Bogin, Benjamin and Hubert Decleer. “Who was ‘this evil friend’ (‘the dog’, the ‘fool’, ‘the tyrant’) in Gedün Chöphel’s Sad Song?” The Tibet Journal, Autumn 1997, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Autumn 1997), pp. 67-78.

Gal, Susan. “Politics of Translation.” Annual Review of Anthropology. 2015. 44:225–40, 2015.

Gendun Chopel. “mi rtag pa dran pa’i gsung mgur,” (Song of Remembering Impermanence) (aka “skyo glu,” Sad Song), in hor khang bsod nams et al, eds. dge ‘dun chos ‘phel gyi gsung rtsom. Vol II. Xizang Zangwen Guji Chubanshe, 1990. pp. 395-399, pp 401.

Lama Jabb. Oral and Literary Continuities in Modern Tibetan Literature : The Inescapable Nation, Lexington Books, 2015.

—. “Knowing Tibet: Centrality of Language and Silences of Knowledge,” Keynote address, 14th IATS Seminar, June 2016.

Lopez, Donald S. Jr. The Madman’s Middle Way: Reflections on Reality of the Tibetan Monk Gendun Chopel. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. pp 32-33.

Leonard, Wesley Y. “Toward an Anti-Racist Linguistic Anthropology: An Indigenous Response to White Supremacy,” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Vol. 31, Issue 2, pp. 218–237, 2021.

Seargeant, Philip. “Language, Ideology and ‘English within a Globalized Context,’” World Englishes, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 217–232, 2008.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books, 1999.

Thurston, Timothy. The Purist Campaign as Metadiscursive Regime in China’s Tibet. Inner Asia, 20 (2). pp. 199-218, 2018.

Notes

[1] My heartfelt thanks to Huatse Gyal, who spearheaded this initiative to gather Tibet scholars around the theme of translation and the richness of Tibetan language. I also thank the panelists, my co-authors in this special issue, for their insightful comments and willingness to share their struggles and concerns. I am deeply grateful to the brilliant Amdo Tibetan woman painter Kulha for her willingness to share her amazing work with us on the cover and inside of this issue. Thanks as well to Rekjong and to Shelly Bhoil for their encouragement to reprise and flesh out our IATS roundtable for this special issue. Finally, my gratitude to Shelly Bhoil and Patricia Schiaffini-Vedani for their careful editing and curation of the issue.

Charlene Makley is Elizabeth S. Ducey Professor of Anthropology at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Her work has explored the history and cultural politics of state-building, state-led development, and Buddhist revival among Tibetans in China’s restive frontier zone (SE Qinghai and SW Gansu provinces) since 1992. Her analyses draw especially on methodologies from linguistic and economic anthropology, gender and media studies, and studies of religion and ritual that unpack the semiotic and pragmatic specificities of intersubjective communication, exchange, personhood, and value. Her first book, The Violence of Liberation: Gender and Tibetan Buddhist Revival in Post-Mao China, was published by UCalif Press in 2007. Her second book, The Battle for Fortune: State-Led Development, Personhood and Power among Tibetans in China was published in 2018 by Cornell University Press and the Weatherhead East Asia Institute at Columbia University. Her most recent project is collaborative oral historical research on the tenth Panchen Lama’s post-prison tours of Amdo in the 1980s.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities