ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

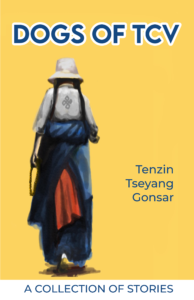

Dogs of TCV: A Collection of Stories

Tenzin Tseyang Gonsar

116 pages, 2020, $9.99 (paperback)

Independently Published

Reviewed by Kalsang Yangzom

Tenzin Tseyang Gonsar’s Dogs of TCV (2020) is a welcome addition to the burgeoning genre of Tibetan Anglophone Literature. A collection of contemporary short stories and poems, Dogs of TCV revolves around the experiences of second and third-generation Tibetans in exile, those who were born in India, and those who then went on and immigrated to the West. Furthermore, the characters in stories have connections to Tibetan Children’s Village, also known as TCV, either as former students or staff. TCV, a system of boarding schools created to educate and house refugee Tibetan children, has had and continues to have a formative influence on a large majority of Tibetans living in exile. Connecting the stories to TCV enables them to be read in a context familiar to many, who will find their childhood reflected in these stories.

The book opens with an aptly titled poem “Refugee”—a word that has come to be a central identity marker for many Tibetans. This poem works as a foreword to the book, placing it firmly within the refugee sensibility, a distinctly contemporary Tibetan way of being, engendered by the twentieth-century geopolitical machinations. The stories, therefore, deal with many aspects of Tibetan refugeehood, ranging from the sweater-selling business to matrimonial ties that facilitate the acquisition of Green Card, from abandonment issues faced by the children sent to TCV at a young age to finding surrogate families among school friends.

Though the stories are grounded in the refugee experience, they don’t overpower the narrative to preclude other universal concerns of love, friendship, marriage, education, etc. “Old Friends that Flow to the East River from Bhagsu via Yamuna” poignantly captures the joy and apprehension of friends uniting after many years. Yangchen and Dorje didn’t part on good terms in India and their meeting in New York is a cause for concern for both of them. But the bond shared by the two in their TCV days and the time spent in Delhi while enjoying the freedom of college days, ease some of that tension, and they go back to being nyingshoe or oldest friends. At the same time, the story also touches upon one of the tried and tested methods of immigrating to the West: marriage. Dorje is the last member of his family left in India; his brother, uncles, and aunts have already immigrated to U.S.A., Switzerland, Belgium, etc. And so, he takes his chance with a friend who is willing to go through this “fake” marriage. The casual mention of scattered families is another reality of refugee people, who immigrate to any country in the west willing to give them asylum or where they feel their refugee status will be transformed to fully-fledged citizenship with all the attendant security and stability.

In the same vein, “Weird Love” is also a story of profound friendships, cemented in TCV but tested by a complex love triangle. Deki, Tashi, and Yangchen take annual trips together, but the trip is cut short this time because of Tashi’s coming marriage. The story delves into the labyrinths of unrequited love, unconventional desires, and marital issues. One gets a sense of the narrative’s contemporaneity not just through its location in the twentieth-century New Orleans but also through the romantic concerns of the three friends which are explored with a frankness and honesty not seen before. Challenges of interracial relations, same-sex love, extramarital affairs are juxtaposed to the familial and social pressures and duties expected out of them as second/third generation Tibetans living in the U.S.

A contrast to these human affairs is the eponymous story of the book, which presents an in-depth look at the hierarchies of the dog world in the TCV campus, between the strays and the pets. The story intersperses the personal history of the various dogs with their human counterparts, and we get a glimpse of the symbiotic relationship between dogs and children. The uplifting narrative is a departure from “Unseeing,” another story set in the TCV campus that shows the ugly side of boarding school life, especially for the young and vulnerable children, particularly orphans. Sexual assault and bullying are a part of the school’s reality that is not openly discussed in the community, and thus, writing about it in the stories is a way of acknowledging the victims and their experiences.

The poems intersperse the stories and provide a pleasant change of rhythm for the readers, offering them a novel perspective of the world, sometimes light and fun and sometimes pensive. “Momo Love” is a pure delight to read, the pleasure of eating momo compared to the love for one’s beloved, and “Mcleod Ganj” presents the café culture in the hill station, couched in Korean food metaphors, a raging trend these days, thanks to K-Pop. Consequently, one can see Gonsar’s poetic acumen when reading her poems. However, the stories could do with a stronger syntax and diction which would enhance these wonderful portrayals of a distinctly Tibetan world by providing a succinct narrative.

The book is, therefore, a worthy inclusion to Tibetan Anglophone literature, locating the Tibetan people and their experiences in the here and now, giving nuanced and refreshing narratives that do not give in to refugee sentimentality and abstractions. The ease with which Gonser sprinkles Hindi phrases and lines from Hindi songs in her narrative prose is a gentle reminder of these Tibetan’s second home, India, thereby demystifying the idea of a singular identity based on one’s ancestral home. The stories and poems focus on the material reality of existence, survival, and life as refugees or as children of refugees in a capitalist, cosmopolitan world that is not without its own hurdles. Most importantly, the book is an affirmation and celebration of the new creative outpourings of the coming Tibetan generation in the diaspora, written in the English language, and an encouragement for would-be Tibetan writers to express themselves and write themselves in the stories they had wanted to read as readers.

Kalsang Yangzom has taught English Literature at colleges in the University of Delhi, India. Her research focuses on the study of Tibetan Anglophone literature and its ties to nation, language, and identity vis-a-vis exile and diaspora as well as literary categories such as national and world literature.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities