ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

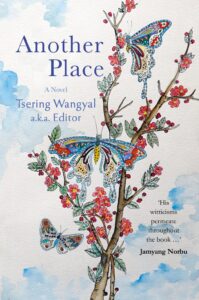

Another Place

Tsering Wangyal

298 pages, 2020, Rs. 200 (Paperback)

Blackneck Books

Reviewed by Jyoti Deshwal

Of Survival and Perseverance in the Face of Displacement

One of the incidents in Late Tsering Wangyal’s novel Another Place, in which the Tibetan exile administration asks a Tibetan to apologize to an Indian over a fight despite no fault of his, brought me a strong déjà vu feeling. It so happened that in one of the Central Tibetan Schools in India, I reminded a Tibetan, who flung a stone at me, that he was an outsider in my country. I was a class 4 student at that time to understand the snobbery and indifference in our expectation of Tibetans to bear everyday injustices and claim no rights whatsoever because they are refugees. Writing the review of this novel thus comes to me as a personal opportunity of apology and understanding the complex predicament of the Tibetan exile community in India.

Set in Dharamshala, the exile capital of Tibetans in India, late Tsering Wangyal’s novel Another Place is first and foremost an attempt to locate, temporally and spatially, the de-territorialized Tibetan community. Before we enter the world of exile Tibetans, the prologue gives us a glimpse of life at Phari in Tibet in the late 1950s through the story of Poor Chok Samten, a young farmer with a disposition of a middle-aged man, who suffers injustice at the hands of Jhangsur, a self-promoted bureaucrat—all in the face of the imminent danger of Communist assumption of Tibet. Thereafter, divided into three parts, progressing linearly with occasional analepsis, the omniscient third-person narrator of Another Place takes the readers through various spaces, that were once at the margins of India, now inhabited by exile Tibetans—Tibetans’ political center in the abandoned British hill station McLeodganj (upper Dharamshala) and the Tibetan hub Majnu ka Tilla that grew out of a camp in the periphery of Delhi.

Those familiar with the slim but significant body of Tibetan-English fiction would recognize not only Manju ka Tilla in Thubten Samphel’s novel, Falling through the Roof (2008) but also late Wangyal in the character portrayal of Editor. Late Wangyal, who worked as the editor of Tibetan Review from mid-1970 to 1996, had earned the moniker ‘Editor’ for having turned the magazine into an influential print platform for intellectuals to debate political matters as well as Tibet’s cultural and social complexities. It is thus no coincidence that Tsering Wangyal’s novel Another Place, published posthumously, represents the generation of Tibetan Review intellectuals, and delves into the recesses of their consciousness, centered around an incident of computer theft, allowing for a narrative style and microscopic view of things, typical to investigative journalism.

Nawang Sutim (Ngawang Tsultrim before he changed the spelling to make it more memorable and pronounceable), popularly known as Frank Lee, is at the center of the narrative with a reticular structure of streets around him abounding in the social and political life of Tibetans in exile. The novel unfolds with him breaking to the paglug (Tibetan card game) club members the news of the theft of his black notebook computer, which he had bought in America. The paglug members work in different departments of the Tibetan Government in exile. Frank Lee himself serves as the deputy secretary of the Department of Information and International relations of the government after his return from the States as a Fulbright fellow. His job definition, however, is that of a clerk and leaves him dissatisfied.

Wangyal, true to the integrity of a writer, exposes the shortcomings of the Tibetan bureaucracy as well as a few self-serving Tibetans in the system. In chapter five, we are introduced to Jhangsur, the man who had bid farewell to Phari years back on learning that the government was sending an investigator in the matter of Chok Samten’s disappearance. In India, he had written a letter of apology to the Tibetan cabinet and offered his free service, thus getting the position of assistant director at Tibetan Medical Institute. He, however, tells a western scholar that the exile government has become gradually corrupt with unqualified people working for it.

In the vast canvas that Wangyal maneuvers to portray divergent Tibetan characters, manifesting in them their bountiful political and spiritual experiences, the romantic escapades—Thubten’s illicit flirtatious interest in Mrs. Migmar or Frank Lee’s shifting romantic interest between Tenzin Lhakyi and Pema Choezom— are quite prominent. In the last chapter, where Pema Choezom takes the narrative voice, she relays her disappointing experiences in love and asserts:

So the only thing I know now for sure is that whoever I marry, it will have to be a Tibetan. He may be old, ugly, or cruel, or someone even more evil than Ali. But he will be a Tibetan. I would be able to understand him. Even the bad things he may do would not be an incomprehensible terror for me. So I could cope with the situation. (293)

Pema’s justification of her decision speaks volumes about the chasm of comprehension between the exile Tibetan community and the outside world. But it may also be about the fact that exile Tibetans are expected to avoid assimilation and carry Tibetan culture on their backs in the given bleakness of the political situation back home for them.

The cultural acculturation of exile Tibetans is, however, inevitable. Frank lee, Pema Choezom, Kardon Tenzin Lhakyi, and Tenzin Bhuti have all been educated at the Tibetan Children Village (TCV) schools, where the curriculum is largely modeled after the Indian schools. Frank Lee and Pema graduate from St. Stephens and Lady Shri Ram colleges of Delhi University respectively. Pema is privileged to have been sent to an expensive boarding school but is made to spend the last two years of her schooling in TCV to improve her Tibetan language proficiency. Khardon and Pema prefer to communicate in Nepali, the lingua franca of the regions where they have lived. Frank Lee, who has an avid interest in English novels and movies, needs Pasang’s help in writing the notice of his missing computer in the Tibetan language.

Quite interestingly, the cultural assimilation seen in Another Place is two-way—Raju and Birju, two Indians working at One More Chance, speak fluent Tibetan and have only Tibetan friends. The novel also throws light on how the international traction that Dharamshala receives due to the presence of the Dalai Lama benefits the local economy.

There is no doubt a healthy cultural exchange between Tibetans and Indians, but the world that stands out in Another Place is singularly Tibetan. Places like the One More Chance restaurant, where paglug is played over Tibetan snacks, momos, and butter tea abounds with distinctively Tibetan smells and sounds. Dharamshala, referred to in the novel “the little Lhasa in India,” unlike China-towns around the globe, is a place of Tibetans’ political resistance and resilience in the face of adversity. Streets and institutions in Dharamshala are given Tibetan names, such as Gangkyi (Gangchen Kyishong) for the area where the main offices and staff quarters of the Tibetan Government are located. Even cultural objects such as the khata, a traditional ceremonial scarf, and chuba and pangden, a colorful apron worn by married women, have greater significance in the novel. Frank Lee, who is also referred to as chuba chaser, despite not wanting to wear the khata on his wedding and farewell chooses to let it remain, which bespeaks his internal conflict and cultural adherence. Mo, a Tibetan form of divination, is also one of the highlights of the novel. Frank Lee acts on the suggestion of getting a mo to find the whereabouts of his missing computer, and surprisingly he finds his computer in Dharamshala within the time period indicated in the mo.

Tibetan fiction in exile is a testimony of Tibetans’ constant readjustment to the growing uncertainty of their exile, which from an initial temporary arrangement in 1959 has become a long-lasting condition. For the generation of Tibetans born to refugee parents, exile is their immediate and only lived experience of home, albeit reinforced by the desperate circumstances of their stolen homeland and punctured by the dynamics of their borrowed land, and thus the befitting title Another Place.

Jyoti Deshwal is a scholar on Tibetan literature at the Department of English and Cultural Studies, Panjab University, India.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities