ISSN 2768-4261 (Online)

A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities

Weaving the Invisible: Tibetan Imagery, Selfhood, and Surviving

Lekey Leidecker and PC

(All images found are courtesy of Yakpo Collective and Aarya Gallery.)

Lekey:

Joy Harjo writes: I am singing a song that can only be born after losing a country.

Tommy Pico writes: what if I really do feel connected to the land?

Khawa Nyanchak writes: How beautiful is this life.

Things that make me temporarily exit my body:

B-roll in the Chengdu episode, Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations: A bhoepa man plays dranyen on busy streets, people pass him in all directions. I hear the word “heaven”. The caption flashes “[singing in Sichuanese dialect]”. Some people will agree.

You literally make us background, landscape, scenery.

Other white men I associate with Tibet:

Dale Cooper. This is what we mean when we say allyship is fiction.

TSERING DOLMA, Ten Lights, Ten Virtues, Ten Blessings (2014), Oil on canvas © W.Ming Art

“Ten Lights, Ten Virtues, Ten Blessings” by Tsering Drolma: Ten choemeys line the middle of the painting as if they are stretching away from us into the distance. On the left, seven people in women’s chubas of various colors are gathered with their hands in prayer. The two at the front of the group wear shirts and pants and sit rather than stand. On the right, a shrine covered in skulls, with two offering bowls. In the background is a blue sky with clouds in different colors.

With no way to make sense of my existence, is it any wonder I am a poet? My whole life has been training: constructing meaning and answers from fragments and fractures. Poets tell us these fragments are everything.

the experience of fitting nowhere is a poem.

Trying to make links that no one else can see is an act of love.

Sometimes you don’t belong where you are because you belong somewhere else.

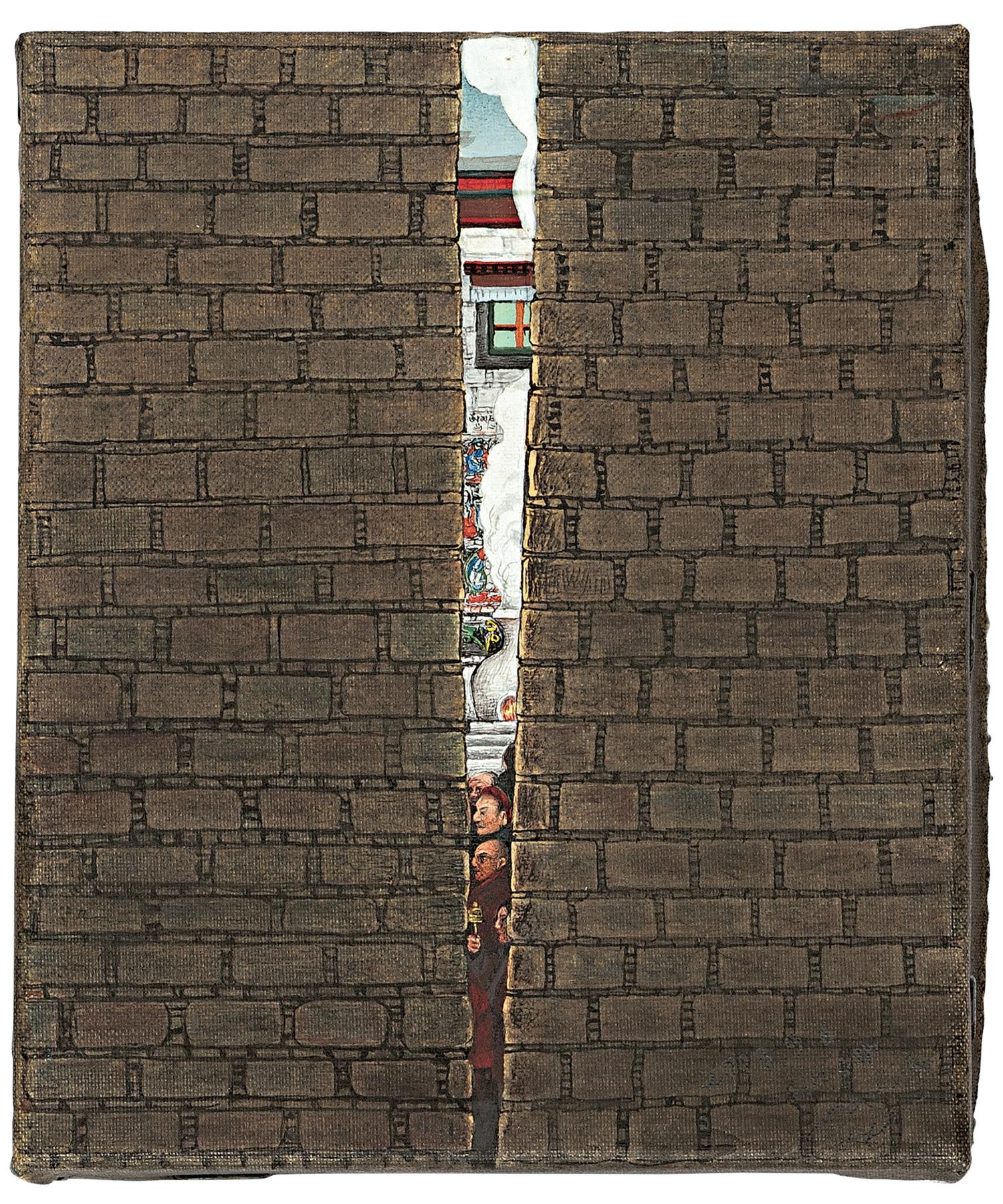

TENZIN DHARGYA, Bharkhor (2013) © 2022 Imago Mundi Collection

“Bharkor“ by Tenzin Dhargya: Two gray-brown rock walls take up most of the painting so we are forced to confront them. In a slight opening between the walls, we get a glimpse of a busy Tibetan scene –traditional Tibetan buildings, sangsol smoke rising, people of various ages doing kora, a slice of the sky. But we cannot take part. At best, we are observers. We are outside it all.

I was raised outside myself. No chance to believe that I exist, so I didn’t. At my core, there is an absence I have not yet learned how to heal. But I know the method: together.

This is what it means to create: Peeking into the beyond. Creating the crack leads to the seeing. By creating the crack, you name the obscuration. But I am tired of cracking.

Youtube video: བོད་ཀྱི་སྟག་ཤར་གྱི་ཚེ་དབང་ནོར་བུའི་ཚོགས་ཁག་གི་འཁྲབ་སྟོན། Tsewang Norbu and four other young Tibetan men on a competition stage. Their moves and outfits somewhere between K-Pop and grasslands, they sing about flowers. I have watched it so many times I am beginning to memorize it. Attempting to freeze them in time and memory.

After a few weeks, the shock has settled into a duller ache of steady grief. Priya’s playlist is there one day, and then it’s not.

Gaslight yourself. © 2022 wikiHow, Inc.

Instagram meme: Wikihow article with an illustration of a white person looking at themselves in the mirror, titled “How to Get Through Tough Times.” Black text reads: Step one: “gaslight yourself.”

Today I told my therapist that I have this feeling that I’m going to explode. I have it all the time, just sometimes I am better at ignoring it. I grind my teeth at night. I give a talk and the audience asks me if they can’t be Buddhist anymore. Imagine asking someone that.

You say: multiply marginalized. I say: It doesn’t matter what I say and that’s the problem. I can barely get out of bed. Reader, the whole thing is rigged – we are living by terms we did not agree to.

My friend / retired psychologist told me that depression is internalized anger.

I carry this feeling around and it blooms when it wants to, with little warning. Exercise helps. Caring attention helps. Weekly therapy helps.

Gratitude exercise meditate

healthy fats

sunlight.

It feels like we will be forever exiled from ourselves and our potential, while more and more people profit from us remaining here, studying, reporting on, photographing us, while the land keeps calling us home.

Call it

What it is, the weight of the ancestors.

My poems use the imagery of heaviness, talk of being weighed down. I am trying to describe something that might be indescribable. I am trying to make visible the contours of my existence.

It is possible that this is why I became an artist at all: The way out isn’t clear, but it is clear that we must find it.

There are more important

things than happiness.

Like staying alive with this name.

It is perfect to just keep living.

I know it feels like being stretched across dimensions. You are. This is what art does– it traverses dimensions. It is of a time and place, it has context, and it helps to expand the world by accomplishing what we’ve been told isn’t possible, doesn’t exist, shouldn’t exist.

I’m writing this because some smart Tibetans believed in me. This is one of the forces holding the world together. Believing in ourselves is a matter of survival.

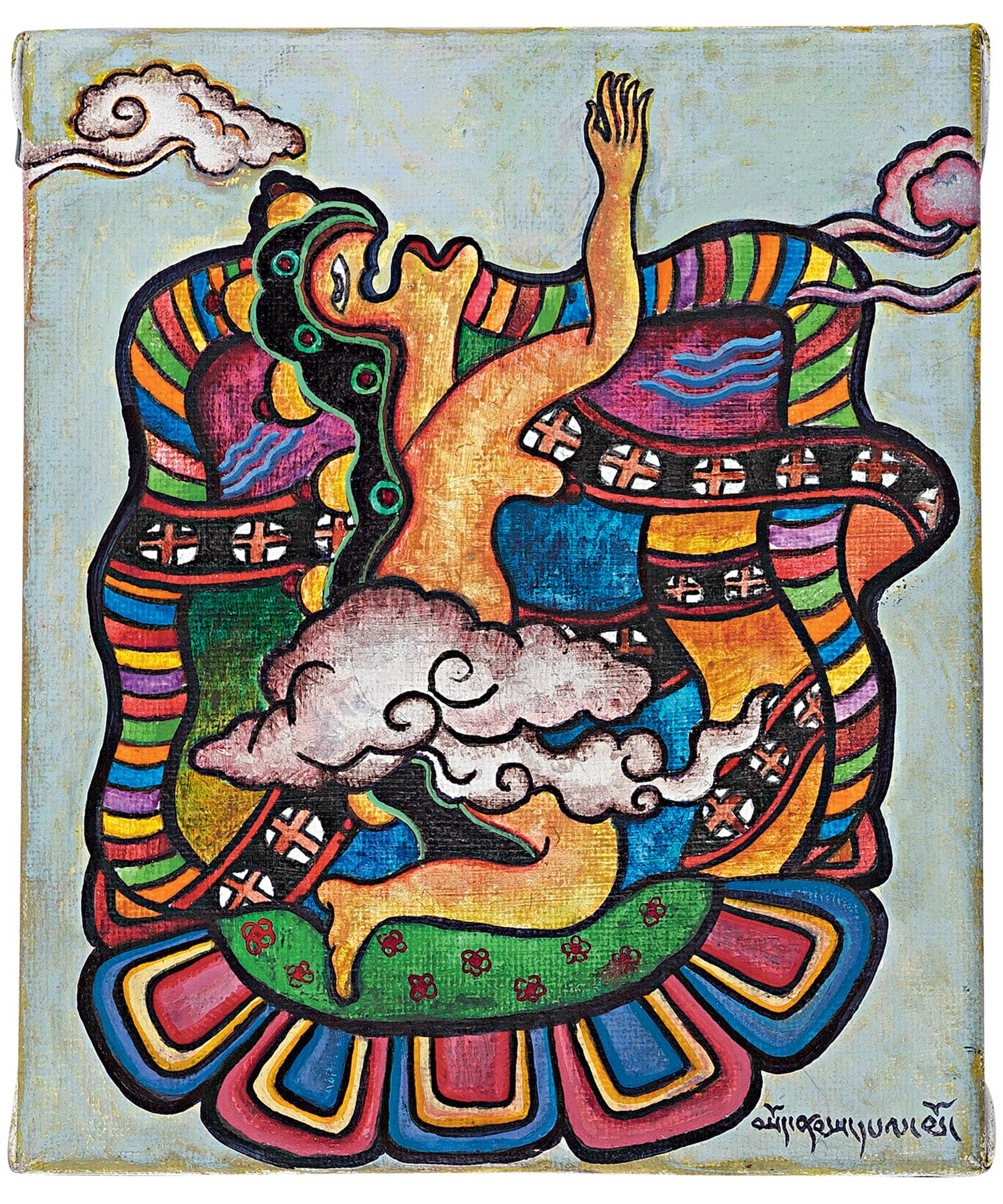

SONAM PELMO, Woman clouds (2013) © 2022 Imago Mundi Collection

Woman clouds by Sonam Pelmo: It’s like if Picasso had been a Tibetan woman, or met one. The woman kneels, hands and face reaching upward. Her entire upper body is above the clouds. Her knees touch the earth. The colors surrounding cohere into familiar patterns I don’t know the names for. I breathe a sigh of relief.

This piece is supposed to be responding to a visual by a Tibetan artist, but it could be to almost any.

In college I learned the sociolinguistic concept of an aesthetic response –a response Louise Rosenblatt describes as “the reader’s attention… centered directly on what [they are] living through during [their] relationship with that particular text.” I respond to everything this way. Every new visual, the existence of the visual, floods and overwhelms me. I have had no time for rigor because I have been desperate to be seen.

I encounter these pieces by chance, shared by a friend or a Tibetan art Instagram account. During the most recent Losar, I kept searching for a filter to only see Tibetans, to not interrupt my feeling of celebration, this tenuous unity. I think I’m going to delete my account. It makes me feel bad about myself.

PC:

Youtube Video: Twelve members of the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) rearrange themselves infinitely on stage to a song from Thod (Western Tibet). The chorus of rhythm is the melody of bodies, the hypnosis of joyful footwork. Bhoepas exist in the afterlives of involuntary movement, so I am breathless when we dance.

Grandmother used to complain when my grandfather listened to Bhodshey (Tibetan traditional songs). It’s too shrill, Bollywood is more pleasant on the ears.

But Pola never stopped listening. I wonder if the songs were his companions when, as a young student, he returned to Lhasa from Beijing. Seventy years ago, there were no railways and networked motor routes across Tibet. Foreign words and Tibetan songs on his lips, Pola did not travel Chinese roads back home.

I am weaved by loom to long threads of ancestors. At the end of the workday, instead of collapsing in relief, I gorshey (circle dance) alone in my room.

Still from Wechat Video, Image Courtesy- JK

Wechat Video: Hundreds of bright orange prayer wheels ring, turning clockwise as far as the eye of a mobile camera can see. Slices of penetrating sunlight dance in a shaky grip. Grandmother’s hands wield mani khorlo and walking stick. I was surprised to discover that she is only seventy years old. Aunt often describes her as ancient, which I never questioned. She speaks of times that live only in our blood memory.

My grandmother lived in Nagchu until last year. She says she doesn’t recognize it anymore. Wondering about the source, I ask after our family home. It has long been 没入, she says.

没入 (mòrù)

VERB

1 plunge; sink; penetrate

没入海中

mòrù hǎi zhōng

plunge into the sea

2 DATED

VARIANT OF 没收

confiscate; expropriate

To trace this term’s burrowing in the story of my fleeting body, I locate myself in the facts. Facts can be manipulated to conceal and reveal, so let me narrate carefully.

In the past ten years, science has decided that Tibetan origin stories are true. Tales of an ancient plateau inhabited by rhinos and elephants traveled roads measured by generations, myth until paleontologists discovered––our ancestors never consented to encounters of exploration—plant and mammal fossils typical of near-tropical climates in Tibet.

As more and more of our homelands become desert, fish are emerging from the mountains. They descend from the ancient oceans flowing over Tibet one hundred million years ago.

We talk about return like a compulsion, as if the source can be neatly traced.

But the bones of our home have long plunged into the sea, returned to pregnant bellies of soil. Mola has migrated to an unfamiliar place where people can help her climb the mountain to perform kora.

In the time beyond endings, I only wonder about the safe passage of our sacred fish, where they might go to circumambulate.

Lekey:

Every second-gen diaspora bhoepa has seen the wall hanging by Kundun instructing us to never give up. It deserves its own essay: The bizarre ways our stuff, wisdom from one of our most brilliant stars in the history of our people, is packaged back to us and we come across it in fair-trade shops, and who even buys these anyway, except to give it to the token bhoepa in their life who already has ten that a pingya brought back from India.

But the absurdity takes away from the wisdom: That is our responsibility, our inheritance, so profound that it borders cliche, printable on a mass-produced scroll-style wall hanging, a Live-Laugh-Love take on a thangka.

But it worked, because as I was writing this, these words I saw on t-shirts, fabric scrolls, postcards, shared on Facebook, revisited my mind, their brilliance and meaning refreshed:

No matter what is happening

No matter what is going on around you

Never give up.

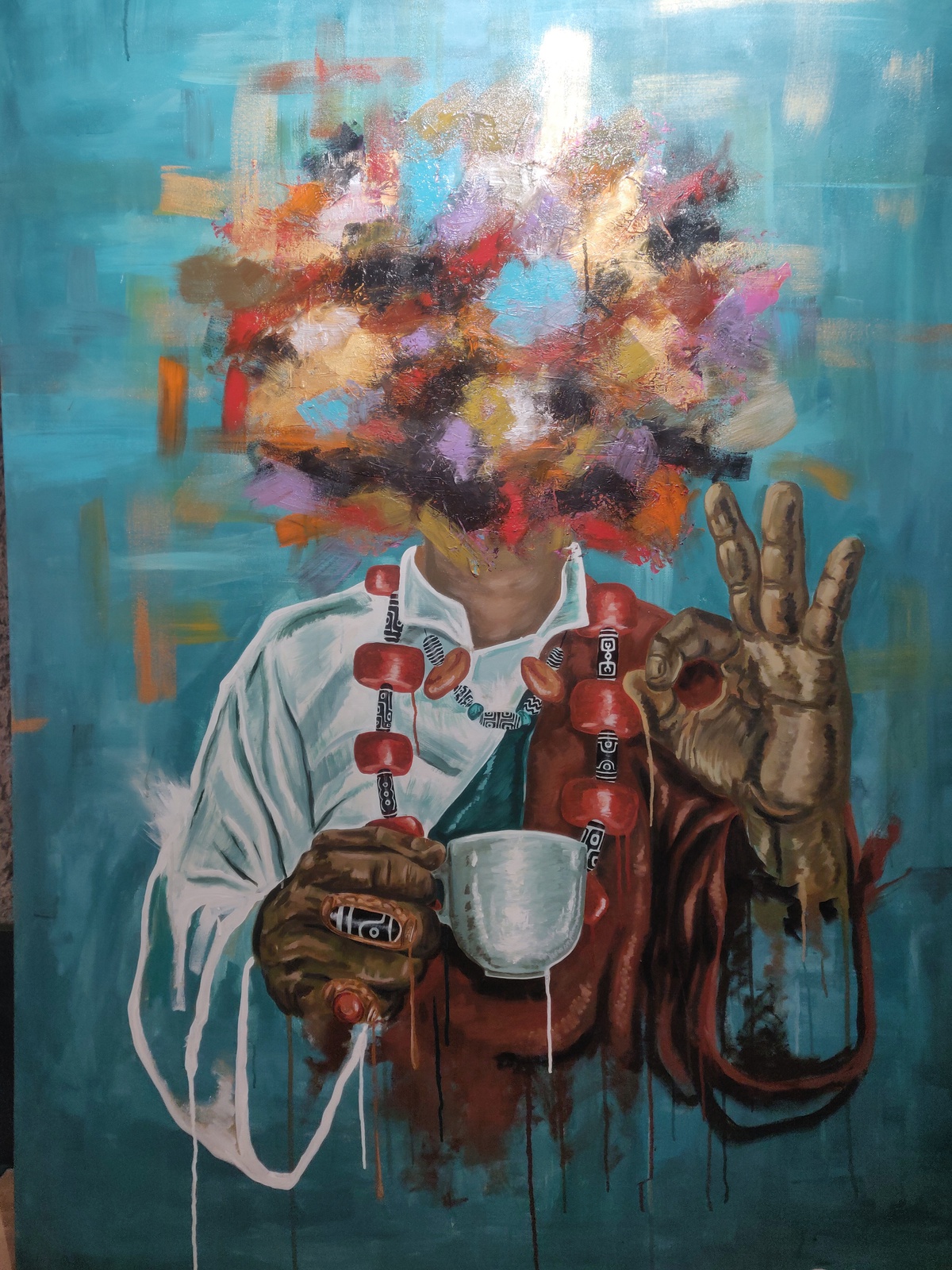

TASHI NYIMA, Highlander Coffee Lover, Image Courtesy- the artist

Highlander Coffee Lover by Tashi Nyima: A person wearing a red men’s chupa, a white wunju, a large coral and dzi necklace, and other Tibetan jewelry. In one hand they hold a white mug and make an “ok” symbol with the other. The person’s head is a multi-colored cloud of paint strokes: black, coral, the blue of the painting’s background, the white of the wunju. The paint drips in places, like graffiti. Like the artist was in a hurry.

Now, we know our angles. We have moved, spiritually and sometimes physically, away from the places that hurt us. I am writing the romcom of my own life. I am my sister’s favorite poet. This is an essay about visuals and how we will make it through to that next place.

I have seen the impossible happen. I have seen the men start therapy and the women set boundaries and begin to thrive, and our queer pingya be embraced and celebrated and live full, complex, glorious lives. These things are happening every day, in very quiet, nyamchung, bhoepa ways. Any day you could meet the friends who are actually just parts of you and who send you $5 or $20 for ཇ་ངུལ་ out of the blue. One day you will look back at this time and think “it wasn’t perfect but look how beautiful I was.”

What I am trying to say is this: it’s not ‘anything goes, use bhod for your own personal gain.’ It’s the opposite. Whether you realize it or not your every single breath is an absolute miracle. Every heartbeat is a gift. You are part of something bigger than yourself every day so I’m begging you- stay alive. You are the art.

Lekey Leidecker is a Tibetan writer born and raised in Kentucky. Her family is from Pemako. She is preoccupied with Tibetan life, identities, time, and land. She divides her time between New York and London. She co-hosts the sporadically updated Srinmo Collective podcast and would love to talk to or write for you about Tibet and feelings.

PC (they/she) is a queer Tibetan-Punjabi femme born and raised in ancestral Chinook and Kalapuya territories (so-called Portland, Oregon). A community organizer, learner, and bearer of their matriarchal lineages, they are committed to just futures where Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples may live joyfully alongside all their sentient relatives. She walks the path to those futures playfully, and earnestly dreams about return and reunion for all Bhoepas.

© 2021 Yeshe | A Journal of Tibetan Literature, Arts and Humanities